By Kevin Jackson, Major

It seems in nearly every New Frontier issue of late that the Western Territory is celebrating another 125th corps anniversary. It was no coincidence that so many Salvation Army corps were established in the American West approximately 125 years ago and a brief look back in history sheds light on this phenomenon.

The late 19th century was an incredibly exciting time in history, particularly in the American West. Technology made the West accessible to the Eastern United States and people took advantage of the burgeoning technology in transportation and communication, traveling west by train in huge numbers. Most sought a better life—including in the cattle industry, farming and oil—and were attracted by the raw energy that spirited the Wild West.

Yet as much of an opportunity as the American West was for those seeking a better life—whether greater economic upward mobility, a chance at a new start in life, or a sense of adventure—there was also a dark side to the Wild West. The big business creating many of the opportunities ran largely unchecked. The economies of the American West fluctuated, while in economic downturn many individuals, families and whole communities faced uncertain and challenging times. Just as in the more developed Eastern half of the U.S., margins were created by the growth in the West. Prostitution, addictions, poverty, loneliness, exclusion and meaninglessness all manifested themselves during this time of great change.

There were also those already in the West—Hispanics had migrated north from Latin America, Native Americans had been here for thousands of years, and Asian immigrants arrived earlier in the 19th century—who were particularly impacted by the expansion west in damaging ways to their cultural, economic and religious lives.

Salvationists who traveled into the world of the American West sat on the same trains as the other settlers with hopes of opportunity. It was opportunity with different motives, but opportunity nonetheless. The early Salvationists were part of a larger Progressive Movement that rose up in response to the fallout of the industrialized world. Their motive was not simply a secular one, but one motivated by the love of God. They certainly wanted the world, God’s Kingdom, to be a better place, but were seeking a social justice with a strong emphasis on the spiritual conversion of those they hoped to serve.

In his writings, a recently emigrated Irish Salvation Army officer, Alfred Wells, spoke candidly regarding the train trip into the landscape of the American West. His thoughts centered on anxiousness, excitement, wonder, and anticipation of a great adventure—a common theme for travelers west.

The pattern of movement for The Salvation Army has been described in a variety of ways throughout history. The one I prefer suggests The Salvation Army follows the world as it develops and acts as a compassionate response to suffering, loneliness and loss as it occurs in the wake of modernization. So the development of The Salvation Army corps in a short period of time in the West would demonstrate such a response. The West could be a harsh and difficult place for the marginalized. The rapid movement and development of corps throughout the region were simply a response to those in need.

A part of the myth of the American West was that it was filled with rugged individualists who wanted to experience the freedom and open spaces of the place. While there were such folks there, they weren’t representative of most who came west. Small town communities quickly formed and dotted the landscape because people were created to be social. Salvationists made an effort to move into any community where they felt a need existed and manpower was available. When we study the rapid development of corps during this period in time we see Salvationists following the railways, getting off the train in a community, establishing a corps, and in a few weeks boarding the train again to move forward, leaving a cadet (Salvation Army version of a seminary student) and locals to keep the new corps growing and serving the marginalized.

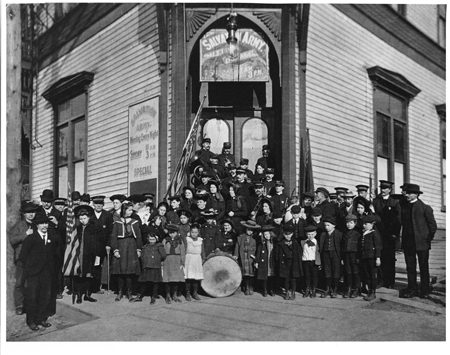

During those years, the inclusive nature of the local corps was evident and is evidenced in photos of The Salvation Army in communities across the West. Apparently, everyone—regardless of race, class or culture—was welcome at a time when America was strongly segregated along these lines. Among my favorite photos of early Salvationist work is one from Silverton, Colo., of a Salvationist all-female string band in 1888. Silverton, a mining town, struggled with all of the social issues of the day and the photographed women represent the demographic makeup of the community—Western European, Eastern European and African American—participating together in a corps activity.

While some of these corps no longer exist, as many of the communities where they operated no longer exist, we see in so many 125th anniversary celebrations that many corps continue to serve the same communities.

These 19th century corps of the American West offered any individual, mostly those in need, a place to be welcome and accepted. The corps was a place of safety, belonging and redemption—often the only place serving suffering humanity in these early communities.

The Salvation Army represented common people living out their faith in a manner caring for those who found themselves in need of compassion, material need and meaning for their lives. It was a great formula 125 years ago and it still challenges us in our ministry today.