How a handful of women changed the world

By Kevin Jackson, Major –

Salvation Army women redefined womanhood for many of their working class peers from 1880-1920. That said, these women should not be thought of as a static statistic for some model of feminism. Instead, these women led complex and dynamic existences, which brought substantive change, not only to their own lives, but to thousands of others as well. This period in American history, known as the Progressive Era, was a time of great social revolution and The Salvation Army women of the day were at the leading edge of its changes in our country.

Most working class American women at the time fit into three well-defined roles in society—either as a factory worker, a domestic worker in a hotel or a private residence, or a prostitute. All three options were unpleasant at best. Most of these women were also married with children and had those responsibilities in addition to their full-time employment. Factories were unsafe, unwanted sexual advances were common for domestics, and a life of prostitution in many cases was the very definition of what we know today as human trafficking.

Their wages were far less than what was needed to provide for themselves or their families. Working conditions were deplorable and the work hours far exceeded what we would deem acceptable in our world today. Many of these women worked at more than one job and for some, prostitution was their part-time job in addition to their factory or domestic work. Unlike middle class women of the time, who made up the first generation of college educated women in history and possessed at least limited opportunities of professional employment such as nurses, teachers, and social workers, working class women had few healthy, safe or edifying employment options in life.

Religious faith provided working class and poor women a hope for the future, but that hope usually came in the form of an afterlife. Yet, The Salvation Army appeared on the scene in American urban centers in the late 19th century and changed the world for marginalized women in profound ways as hope became something for the here and now.

The Salvation Army practiced a type of faith that provided an avenue to Christian faith, but one that believed the present world could be transformed of its societal ills, and they set out to do just that. At the heart of this urban ministry of transformation were women Salvationists. Most were working class women who converted to the Christian faith, joined The Salvation Army, trained as clergy and then were deployed back into the urban centers from which they had come. These women, who in many cases were trained to work specifically in the worst neighborhoods and communities, were known as “Slum Sisters.”

The Salvation Army practiced a type of faith that provided an avenue to Christian faith, but one that believed the present world could be transformed of its societal ills, and they set out to do just that. At the heart of this urban ministry of transformation were women Salvationists. Most were working class women who converted to the Christian faith, joined The Salvation Army, trained as clergy and then were deployed back into the urban centers from which they had come. These women, who in many cases were trained to work specifically in the worst neighborhoods and communities, were known as “Slum Sisters.”

It is easy to look past the transformative empowerment that occurred for the Salvationist woman. For many, their former life was at best a dreary, hopeless, day-to-day experience. They didn’t have the hope to attain the limited opportunities of middle class women of their day. Those of the first generation of college-educated, middle class women were known as the “New Woman.”

For the first time in American history, the New Woman chose economic independence while living and working outside of the traditional home setting, becoming part of the public sphere in American society. This opportunity was only available at the time to middle class women. The Salvationist Woman of the same era, however, presented the opportunity for such an existence to also be enjoyed by working class and poor women. The egalitarian nature (women viewed as equal counterparts to men) of The Salvation Army provided working class women an opportunity for a vocation beyond the accepted limitations they had previously experienced.

The Salvationist Woman was economically independent and very much a part of the public world. These opportunities, rather common for most women today, in the late 19th century were world changing events in the lives of these working class women and the thousands of lives they touched through their faithful devotion to building God’s Kingdom.

The Salvationist Woman of the late 19th century changed their world in a rather distinctive way. They didn’t view their position of leadership in The Salvation Army as upward mobility. They didn’t join The Salvation Army and then seek to leave the pain, suffering and danger of America’s cities. Rather, they remained in American urban centers and actively sought grassroots reform, both religious and social, for these poverty-ravaged communities.

The Salvationist Woman became a model of Christian leadership and servanthood. For these women, bringing about social and spiritual redemption of individuals and society was manifested in the communities where they were born and raised.

In certain respects, the Salvationist Woman was not unique for the world she occupied. Many Christian women utilized their religious faith to make their lives and the world a better place. For example, the African-American women of the day were a strong force in their communities for social and spiritual change, mostly as volunteers, using their Women’s Clubs as a source of improving their communities.

The first generation of college-educated women social workers were flocking to urban centers and combining their faith and education to work in poverty stricken communities through the Settlement House Movement, which provided needed social services to the poor in the inner city, highly immigrant populated areas. These college-educated social workers would live at the Settlement House and provide services to their neighbors in need.

The Salvationist Woman was unique in that in addition to providing social services in some of these most impoverished areas of the American inner cities, she also functioned as an ordained clergy member, holding a credential equal to her male Salvationist counterpart. Just the fact that she was fully ordained and held a commission in The Salvation Army in her own right was a rarity in the late 19th century. Some historians look back and over-analyze the details of the Salvationist Woman’s standing as officers in the Progressive Era, but failure to recognize this amazing detail simply minimizes the historical importance of the Salvationist Woman.

She was almost exclusively working class, although there were a few college-educated Salvation Army women officers from middle class backgrounds. For example, Vida Scudder, who went on to be a significant Christian social worker in her day, first began her career with The Salvation Army, but quickly relinquished her officership as the life of a Salvationist Woman was far too challenging and difficult, and the lifestyle clashed with her middle class sensibilities.

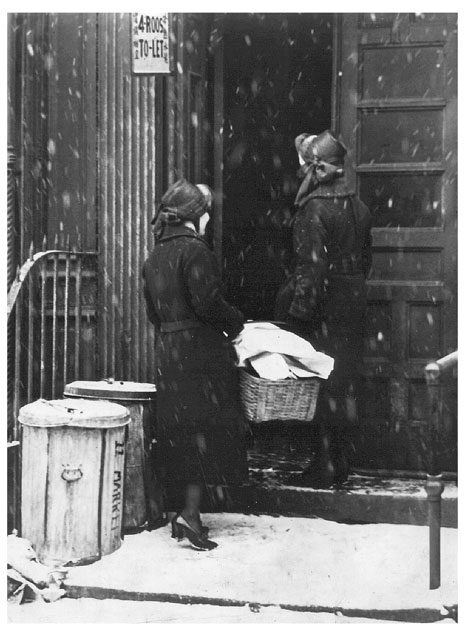

The daily life of the Salvationist Woman looked fairly similar in most places. The inner city ministry of the Slum Sisters began in the late 1880s. A primary focus of the Slum Sisters included, but was not limited to, offering services to pregnant unmarried women, providing women an escape from a life of prostitution, establishing childcare for working class women employed in factories or as domestic servants, and promoting evangelistic street ministries. These activities were groundbreaking and transformational in their day as the Salvationist Woman’s ministry was at the cutting edge of social reform and a radical model of Christian faith.

Childcare was an unknown entity in the world of the Salvationist Woman, especially for a working class mother. It was not uncommon for factories to dispense narcotic drugs for mothers to give to their preschool children so they would sleep during a woman’s shift at the factory. The idea of providing a clean and safe place to leave your child while you worked at a factory transformed the world for women and children alike. In this context we see the powerful nature of childcare for the poor.

Offering programs to reform prostituted women provided tangible hope for young women as well, many who were teenagers, and a real opportunity to escape a life in the streets or brothel. Several of the Slum Sisters were reformed prostitutes themselves.

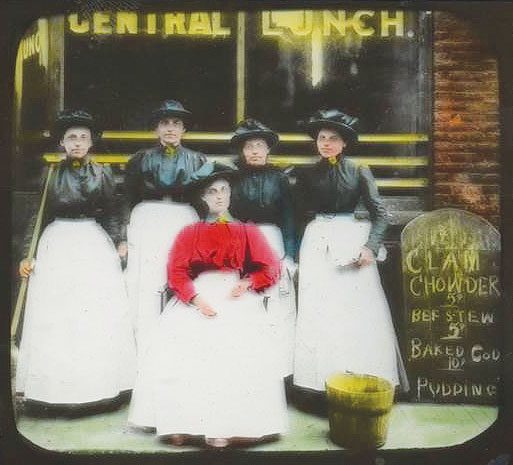

In 1892, The Salvation Army opened a facility to train Salvationist women in these specific types of work. The Slum Sisters wore no standardized uniform in their day-to-day activities. Their clothing was designed to hold up to hard work, and hard work was what they were known for. The Salvationist Woman would open workingman restaurants where the urban poor and working class could get an affordable meal. Feeding and clothing babies, as well as preparing the bodies of recently deceased homeless for the undertaker were all activities common to the Salvationist Woman. They cleaned homes for those too ill or elderly to care for themselves and while sobering up drunks, the Salvationist Woman darned their socks and patched up their clothing. Even the greatest critics of the work of The Salvation Army fell silent when it came to the work of Slum Sisters.

The Salvationist Woman tended to be single and in her mid-20s. She lived and worked with other Salvationist women and depended on the strong bonds of friendship that developed between them. These relationships were an important support network for the women as their chosen vocation was extremely demanding and difficult. The Salvationist Woman and the strong friendships between them nurtured their mutual mission for social justice and lead individuals to an acceptance of the Christian faith.

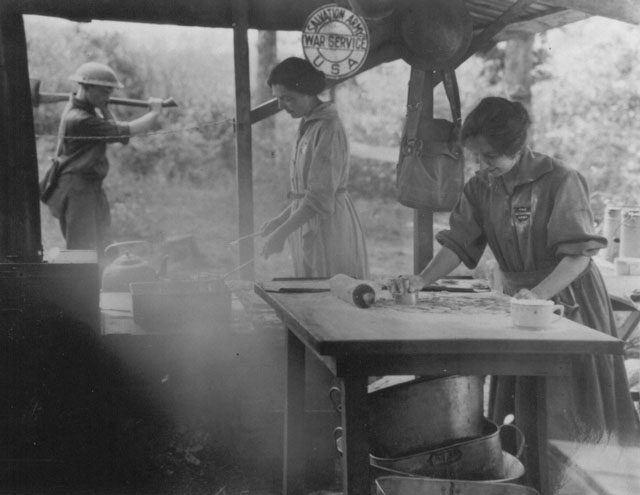

After years of faithful service in America’s cities, World War I broke out. When time came for the United States to enter the war, it was the Salvationist Woman who was called upon to serve the American troops in war-torn France. The Doughnut Girls, as they lovingly became known, were for the most part Slum Sisters who had previous years of demanding service prior to the war, living and working in severe poverty. The same grass root care they provided the poor living in American slums, they now provided the American soldier during a time of war.

As groundbreaking a model of American womanhood as The Salvationist Woman was, the Slum Sisters took their model of servant leadership to another level when they became Doughnut Girls. Their ministry in Europe during World War I not only proved effective, but it essentially vaulted The Salvation Army into the mainstream of American consciousness and society back home. The Salvationist Woman was in great part responsible for The Salvation Army that emerged in and throughout the 20th century in the United States.

It’s difficult to overestimate the importance of the Salvationist Woman who lived and served from 1880-1920, as their story demonstrates what sincere, committed and trained individuals can accomplish through their lives and in the lives of those they serve day to day. The Salvationist Woman emerged from a dismal and dangerous existence as part of the working class and urban poor in American cities, to first transform their own lives through faith and later the lives of countless others from the margins of society. They stood apart from so many in history as they chose a life of servant leadership and boundless compassion for others.

_________________________________

Further reading

Christians for Biblical Equality (cbeinternational.org)

Great Women in Christian History: 37 Women Who Changed Their World (Christian History Institute, 2005), by A. Kenneth Curtis

Marching to Glory: The History of the Salvation Army in the United States, 1880-1992 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995), by Edward H. McKinley

Hallelujah Lads and Lasses: Remaking the Salvation Army in America, 1880-1930 (University of North Carolina Press, 2002), by Lillian Taiz

Women in God’s Army: Gender and Equality in the Early Salvation Army (Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2009), by Andrew Mark Eason