According to Bloomberg, California is poised to overtake Germany as the world’s 4th largest economy, behind the U.S., China and Japan.

California continues to outpace other states and other countries in GDP growth, companies’ market value, renewable energy and more.

From these metrics, you might presume that the “California Dream” is alive and well.

Yet, despite California’s economic might and world-class growth engine, one of the biggest problems plaguing the state is growing right alongside its GDP.

California has dominated the national conversation on homelessness. And justifiably so.

As of 2022, 30 percent of all people in the U.S. experiencing homelessness resided in California, including half of all unsheltered people.

In a recent poll, 84 percent of Californians said they think homelessness has become a “very serious problem.”

It’s not for a lack of investment. Officials spent more than $17 billion to address homelessness over just a four-year span in California. And yet, the state’s homeless population actually grew over that period.

It’s an all-too-familiar paradox in the arena of homelessness—spending increases, and yet, somehow, the issue worsens.

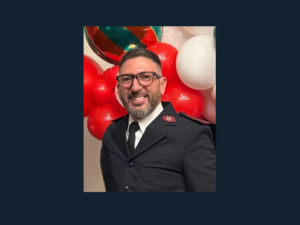

To help us understand why so many efforts to curb homelessness have fallen short and which strategies deserve more of our attention, we’re talking today with Andrew Hening.

Andrew is a UC Berkeley MBA with nearly 20 years of social sector leadership experience. He is currently consulting with public agencies to measurably reduce homelessness, spark civic innovation, and redesign systems of care for homeless and at-risk populations.

In 2018, Andrew was named the top national influencer in local government by Engaging Local Government Leaders for his work with the City of San Rafael. There, Andrew helped break down the complex issue of homelessness and mobilize the community around lasting solutions.

He’s also the author of “So You Want to Solve Homelessness? Start Here,” helping us understand the issue, what efforts are effective and what communities can learn.

Show highlights include:

- Andrew’s personal journey to working on the issue of homelessness.

- What his book, “So You Want to Solve Homelessness? Start Here,” zeroes in on.

- Why homelessness has gotten so bad in the U.S.

- Why most efforts have failed.

- What actually works.

- More about Andrew’s work in the City of San Rafael that led to recognition as the top national influencer in local government.

- How Andrew figures out which strategies will be effective for various communities.

- His new course, “A Civic Leader’s Guide to Solving Homelessness,” and how he designed it.

- What individuals can do to accelerate the progress toward ending homelessness.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: Well, Andrew, welcome to The Do Gooders Podcast. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Andrew Hening: Absolutely. Thanks, Christin. It’s an honor to be here.

Christin Thieme: As we get started here, can you share a little bit of your own personal journey, maybe especially that led you to dedicate over a decade now of your life to the issue of homelessness? And from what I’ve heard about you, maybe you could include your decision on how you drove across the country to join the movement way back when.

Andrew Hening: Yes. Well, as I’ve discovered over time, like many people in this field, I sort of came into it by accident or I never intended to. So, when I first graduated from college back in 2008, I had aspirations of being a lawyer and I was working at a law firm studying to go to law school. And to my surprise, I discovered that even though I loved my coworkers, I really did not like the actual job of being a lawyer, being an attorney. So I started taking off work, volunteering at different places in the community. I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and I think what happened at that time was, like I said, I graduated in 2008, so right into the Great Recession. My dad was a carpenter, he’d been in construction his whole life and he lost his job ultimately, permanently because of the recession.

And so, I got really interested in community development, economic development. And so as I was looking for different opportunities, I discovered something called Project Homeless Connect, which is basically a one-day resource fair for people experiencing homelessness, and that was in Richmond, Virginia. And I was so blown away by the experience that I ended up looking for other opportunities in homelessness, and I discovered through AmeriCorps VISTA the opportunity to lead Project Homeless Connect on the other side of the country, in Santa Clara County, San Jose, Silicon Valley, that area. So, I threw everything I owned in the trunk of my car, drove across the country in 2010, and I’ve been at it for the last 13 and a half years.

Christin Thieme: Amazing, and you wrote a book which is titled, So You Want to Solve Homelessness? Start Here, which really zeros in on the issue of homelessness in the United States. What led you to write the book? You were engaged in this work, but why did you want to put that into a book and what were you hoping to achieve with it?

Andrew Hening: So, when I first got to California and started working on this, I thought homelessness was so simple. The solution is in the name itself, people don’t have homes, that’s the solution, we need more housing for people. And I honestly thought that I’d be working on this issue for maybe one, two, three years. So, there’s a kind of a funny story where at that time when I was with the city of San Jose, I was going on a tour of downtown and we were getting updates on different capital projects and construction projects and things that the city was working on. And out here in the Bay Area, there’s this transit system called BART, and the goal was that BART ended in Fremont, which is a city about 20 miles north of San Jose. So, the goal was within 10 years to connect BART and Fremont to San Jose.

And I remember thinking, I can still see it today thinking, “There is no way I’m going to be working on homelessness 10 years from now. We are so close to solving this, it’s so straightforward what we need to do.” And again, lo and behold, I’ve been working on this for over a decade. And what happened was that I had the chance to work on this issue from a variety of different ways, from Frontline Street Outreach, working in nonprofits, working in city government, and what was really challenging was that in all these different roles, I saw what felt like success.

We were helping people get jobs, helping people get housed, and yet at a large scale level in California and across the country, homelessness was actually getting worse. And so, I started this journey of basically researching, what are the underlying issues that are actually driving homelessness in our country and if I can, create some kind of unifying explanation of how we got here? And I really approached it from the thought of this is the book that I wish I could have read on day one to really understand how we got here.

Christin Thieme: I love how simplistic it is. It’s such a complex issue, but in your book you make it very straightforward. There’s really these three fundamental questions. So, I wanted to touch on them if you don’t mind, because they’re really good ones, and I think for people who don’t understand the issue fully, these are a great place to start. So your first question is, why has homelessness gotten so bad in the U.S.? What would you say are the main contributing factors to the current state of homelessness that we see in California and across the country?

Andrew Hening: It’s a great question, and I think something you said, the current state is really key. So, I’m a millennial. I was born in 1986. I’ve never known a United States without homelessness, and I think that can lead to this really challenging belief or assumption that homelessness then is just inevitable, it’s always existed in our country. And I think there’s this very powerful feedback loop at the root of homelessness today that we feel that it’s unsolvable, we don’t make systemic investments to try to solve it, and thus it gets worse, which reinforces this idea that homelessness has just always existed. One of the things that I surfaced in researching my book was that there’ve actually been many eras of homelessness throughout our nation’s history, and they are each driven by different socioeconomic trends or patterns in the broader country at the time. So for example, 120 years ago, the United States looked very different than it is today.

It was a rapidly urbanizing country, so if you’ve heard the term hobo, that originates from that time. That was people who were engaged in essentially migratory labor, going from city to city to try to find economic opportunity. There were actually more people experiencing that type of homelessness than are experiencing homelessness today. That’s how significant it was, but that mostly went away as the country finished that sort of period of urbanization. Fast-forward to then the Great Depression, we all know there was this significant economic crash in the late 1920s into the 1930s. If you look at pictures from that time, read histories from that time, you see things that look almost like homeless encampments today or other features of homelessness today, but certainly those manifestations of homelessness at that time or the economic catastrophe at that time went away. We came out of that depression.

We had a resurging economy into World War II, and thanks to the New Deal. So what I really discovered, and I think the key driver today is that there is this unique period of homelessness that began in the early 1980s. I refer to it as the modern homelessness crisis, and it’s very complex, and we can maybe talk about more features of it, but the two biggest features in my view are one, there’s been a steadily increasing cost of living in our country, which is making it more likely for individual crises to result in episodes of homelessness.

And there’s also been an erosion and underinvestment in health services, particularly behavioral health services, so mental health services, addiction services, and that has led to a really key fundamental insight, which is that for most people experiencing homelessness today, it’s actually a relatively short-term experience, lasting a few weeks or months. And it’s primarily driven by economic or relational crisis. By comparison, there is a small, but persistent minority of people, this is folks called people experiencing chronic homelessness who’ve been experiencing homelessness for years, even decades in some cases, and that is exacerbated by underlying healthcare issues such as, again, mental illness, addiction, traumatic brain injuries, or oftentimes many of these issues combined.

Christin Thieme: So, many things going on. For somebody who’s not as immersed in the world, it can be hard to really get a handle on it. And like you said, it almost becomes just this is the way it is, but would you say homelessness is solvable?

Andrew Hening: 100 percent, again, I think for me, just knowing the history, knowing that this is not an inevitable feature of our country, of our society, I think that really helps to make it clear that we can change policies, we can make investments to get ourselves out of this. And then also just at a more individual level, there are communities across the country that are driving significant decreases in homelessness. They are having a lot of progress around homelessness, so between both the history and the current contemporary success that some communities are having, it’s clear that there are ways that we can do better and be better around how we approach this issue.

Christin Thieme: Absolutely, so the second question you pose is, why have most efforts to solve homelessness failed? For years, experts, researchers have pointed to the affordable housing crisis that essentially you can’t solve homelessness without seriously addressing our housing shortages, obviously, but how does the lack of affordable housing play into this broader conversation on homelessness?

Andrew Hening: Housing is 100 percent at the core. I think that original intuition I had all those years ago is still there, though there’s a little bit more complexity and nuance around how we might think about it. To put some hard numbers to this, we’re really talking about the cost of living, especially on renters. So every year, Harvard University, they put out this incredible study on the state of the nation’s housing. And what they’ve found is that when you adjust for inflation, the median rent price in our country since the 1960s has increased over 60 percent. By comparison, the median renter’s income has only increased by 5 percent. And there are a lot of reasons that are both driving the cost side of things, as well as depressing the revenue side of the actual economic assets people have to respond if they’re in a crisis, but that’s this core dynamic.

And as recently as 2020, there was a federal study that found that for every $100 increase in rent in a community, there is a 9 percent increase in homelessness in that community, so there’s a very direct link there. What’s tricky and difficult, and this is where I talk about the complexity of the housing issue, is that the housing crisis is not just one thing. So for example, one of the big drivers of the cost of housing, especially in large metropolitan areas, is that over time we’ve added a lot of regulation around how we guide and inform investments and development around housing. And again, a lot of those come from good places of trying to protect the environment and other things of that nature. But unfortunately, a lot of those policies have also resulted in dramatically slowing down the growth of housing, again, particularly in metropolitan areas.

The interesting thing though about seeing this as more of a systems problem is that even as states like California have begun to make steps to improve that, certainly have not… I think there’s much more that can be done, but even as you now see improvements in that kind of regulation around what can be built where, this has occurred at the exact same time that we’ve seen this rise in inflation following the pandemic, and so even as it’s easier maybe regulatory wise to build, the cost to build has gone up, so you’re not actually seeing this growth. So, housing is absolutely at the heart of this, and it too is its own complex system that I really try to deep dive in the book and explain, what are the levers that we can pull to really make progress on this and increase our supply of housing?

Christin Thieme: One of the most surprising questions for anybody who is working on the issue of homelessness is, what actually works? Which is your third question. Can you share some insights from your experience about, what are some of the effective strategies and approaches? What exactly has made them successful? You mentioned some communities are seeing some success, so what are you seeing out there that works?

Andrew Hening: Absolutely, so one of the really interesting things, even since writing the book that I continue to think about this and, “Oh, should I have said this or changed this?” Is at its essence, as I described, the modern homelessness crisis is really a symptom of other problems. So the housing crisis, declining wages, systemic racism, all of these things are making it more likely for people to fall into homelessness. These things are happening all across the country. They might have different weights in different communities, but again, it’s a national trend. Even though this is a national crisis then, the way we’ve actually responded to homelessness is hyper-localized. So for all intents and purposes, every city, county, region is more or less left to their own devices to figure out how to respond. And it is that nature, that structure of the response, which has actually made it even harder to solve for a variety of reasons.

And so as just one example, I spent almost 10 years working in Marin County, California. This is an affluent suburban community north of San Francisco that is not typically thought of as a place where you would have a lot of poverty or a lot of homelessness, but as recently as 2017, Marin had the seventh-highest per capita rate of homelessness in the entire country. And what’s interesting is having worked within that community, within that system, something really dramatic happened. And if you ask people from that period of time, roughly 2015, ’16 to probably 2019, they probably each tell you something different.

We started going on field trips to other communities, we started having national experts come and talk to us about, what are things that are working across the country? We joined national movements that are trying to create better systems of care. So, the short answer back to your original question is that as I’ve tried to reverse engineer, what was the magic that happened? The real magic is fighting this tendency to hyper-localize the response to homelessness, because as you can imagine, there are all across the country, different outreach programs, different shelter programs, different housing programs.

And so really the goal should be, how do we look beyond our local system, find best practices in other communities, and then implement those locally? And if we’re already the best practice, how do we continue to innovate and try to do even better? So that to me, building this local momentum to try to have the best possible system as benchmarked to other communities is probably the most effective way for local communities to really drive change around homelessness.

Christin Thieme: Was it that experience that you were recognized by the local government for your work as the top national influencer?

Andrew Hening: It’s hard to say because at the end of the day, I don’t know who nominated me for that. So, it’s hard to say what maybe they were thinking, but I think a really big part of it is… just to share another story. So, I started working in Marin in 2013, and at that time, Marin County and San Rafael, which is Marin’s largest city, which is still a relatively small city, was having a major issue with homelessness in the downtown. And I think this is a phenomenon that’s happening all across the country in cities small, medium and large, where in these kind of thriving commercial areas, there’s a lot of homelessness and it creates a lot of strong feelings from the community about what to do. And so in San Rafael, I worked as a nonprofit service provider for a couple years, and then in 2016, I started working for the city itself.

And at the very first city council meeting I was at, I’m down in kind of the front right of the council chambers, and the topic on the agenda was whether or not the city should revoke the use permit for a nonprofit service provider in the downtown because half of the community felt that this service provider was a magnet that was drawing people to San Rafael for services. And then the other half of the audience felt like, “No, if anything, we need even more services because clearly there’s a need to help people.” And again, I’m down here looking back over my shoulder like, “I’ve made a colossal mistake taking this job. How are we ever going to find agreement around this?” So what happened though was, and I think this is maybe where that honor came from, is that I really tried to approach that job with a sense of radical empathy.

So, when I was a service provider, I certainly approached working with our clients with radical empathy of just understanding what kind of life circumstances might’ve led to them experiencing homelessness. And I brought the same to that work and listening both obviously to people that were experiencing homelessness, but also downtown business owners, parents, you could begin to understand that there was this real… It was actually kind of shocking. There was actually this very strong, almost bipartisan agreement that no one wanted homelessness. We were all coming to it from different angles. Some was around just compassion and human dignity, some was concerns over safety, but when we were all in agreement, no one wanted to see this kind of very intense homelessness in the downtown, but it was really these strong manifestations of people going into businesses and yelling at customers and maybe litter and debris and loitering on sidewalks or active drug and alcohol use on the streets.

And so what we realized, and through all those conversations, is that the issue was not the downtown service providers. The issue, going back to what I mentioned earlier about chronic homelessness, is that we had this relatively small group of people who had been homeless in San Rafael for in some cases, five, 10, 20 years, struggling with mental illness, struggling with addiction, struggling with traumatic brain injury, and other physical health issues that were not being prioritized by the system.

And sadly, I see this in so many communities, it is the negative manifestations of those vulnerabilities that often makes communities unwilling or uninterested to help these extremely vulnerable people. And so, what I would tell community members and really listening to them, I hear your concerns, I would then turn it around and ask, “Really think about it, what would it take for you to exhibit that kind of behavior?”

And nine times out of 10, the light bulb immediately went off. Yes, these are very vulnerable people that we need to help and actually treat with compassion and get them into housing and services. And I think that was the big shift is that we shifted away from that really antagonistic, polarized dynamic to really it felt like the whole community was galvanized around this strategy of we need to reduce chronic homelessness. And what happened was we actually did reduce chronic homelessness from 2017, 2019, we had a 28 percent reduction in chronic homelessness, and the actual conditions in the community improved, and that whole debate about the service center almost entirely went away. So, I think helping to drive and service those insights was perhaps what helped to lead to that honor.

Christin Thieme: Absolutely, and you mentioned looking at communities to see what’s working to implement. Obviously, there’s no one size fits all solution to the issue of homelessness, but we also, like you kind of alluded to, we don’t need to reinvent the wheel every time. So, when you are looking at communities or when you’re maybe consulting on the issue of homelessness, do you have a process to help you figure out which strategies will be effective and what’s your starting point for that?

Andrew Hening: It’s a really, really good question. So, I did eventually make the move from working in local government to then consulting. And so as I moved into consulting, again, I had to try to figure out, how do I reverse engineer what we did as a team and apply this to other communities? And if folks have read the book, or you could also visit… I’ve subsequently set up this website howtosolvehomelessness.org, and I have an updated version of this, but in one of the later chapters, I introduced this idea of STEP, which is essentially trying to create a customer journey map for the experience of people experiencing homelessness, moving through a system of care. And so what is that? What is a customer journey map? And business settings in the private sector, this is a very common thing to basically look at, how do customers or clients move through our services over time?

What are the touchpoints of engagement and how do we maximize the effectiveness at each of those touchpoints through our brand, essentially? And so the thinking was, especially as I started working with more cities and counties and different communities, is that as a movement, as a sector, we’ve done a really bad job of creating a shared framework of how systems of care fit together. What is the kind of standard customer journey map around homelessness? And to basically break it down very briefly, you can imagine… I now call it STEPS, so the first S is societal. So, those are the societal conditions that we were talking about, cost of living, institutional settings in a community, systemic racism, these are the things that are making it more likely for homelessness to happen. T is in triage, that’s when the actual crisis is happening, so someone is either at the risk of becoming homeless or they’ve actually just become homeless.

So, this is an opportunity for a community to try to quickly prevent or rapidly divert someone to get them back into housing before getting into the homeless system of care. If that doesn’t work, you then move on to E, which is engagement. And this is where you begin to see things like shelter, Street Outreach, mobile shower programs, food programs. It’s basically all of the ways that we can try to engage people once they’re actually experiencing homelessness. And then P is placement, which is of course the ultimate goal of getting people back into housing, and then the final S that I added later stands for systems, and it’s these undergirding things of leadership and data and funding that influence all of the different aspects of that customer journey map.

And so, basically what I have started doing now that I’ve been consulting, and again, there’s more resources that you can just read about on that website, is when I go into a community, I will interview folks, I’ll do lived experience sessions, getting feedback from people that are currently or were formerly homeless.

I’ll do community events and other public engagements to get feedback around what in terms of our customer journey map are the weak points? Where do we need investment? Where can we immediately begin to scale up and do better? And I think what I’ve also just kind of intuitively learned over time is that, like I was saying earlier, I now know and I’m hoping to help put out more information around this, these are the benchmarks, if you look across a region, across the state, across the country, of how to best do these different interventions. So Street Outreach, these are the best practices that are going to get you the best results for that particular intervention. And so, you can rapidly then in terms of strategic planning, try to help communities get to those best practices. And if they’re already there, again, how do we innovate and improve?

Christin Thieme: A lot of resources, thank you for that. One of them, you followed up the book with a video training course that’s called The Civic Leaders Guide to Solving Homelessness. Can you tell us more about who exactly is that for and what do you intend they take away from it as a follow-up to the book?

Andrew Hening: I always sort of had this in the back of my mind when I was writing the book. I think the book is really intended for more of just the general public, so anyone that’s interested in homelessness and how we got here and how can communities begin to make progress. That’s really what the book is about. And the training course in my mind was always, okay, you’ve read the book and now perhaps you’re in a position of leadership or influence in your community, how do you actually drive that change? What’s the actual toolkit for making progress? And so, the way that I’ve been thinking about it is that…so, as of the end of 2023, there are about 600,000 people who are experiencing homelessness at any given moment in our country.

And what’s interesting is that the federal government requires local communities to organize what are called continuums of care to try to bring city, county service provider, government agencies together to try to plan their response to homelessness. Now, what’s interesting is that if you look at the COCs across the country, there are almost 400. The top 20 percent of COCs or COCs that have about 1,600 or more people experiencing homelessness, they account for 70 percent of all homelessness in our country.

And so, if you imagine that each of those COCs has county board of supervisors, city council members, a mayor, some major service providers, some major funders, in total, there might be about 100 really consequential leaders that are hopefully working on this issue. And so, my hope is that if we can provide a toolkit to get those 100 people, and then across all those communities, about 10,000 civic leaders with this kind of shared understanding of how we got here, and then a shared strategy of how do we begin to move forward learning from each other as I just described, then we could really make dramatic progress around this issue. So, that’s the ultimate big goal of the course is to try to accelerate progress around homelessness in our country.

Christin Thieme: So, tell us again how we can find all those resources, how we can connect with you. And then as a last question for anybody listening, maybe they are just somebody who’s interested in the issue, maybe they are someone who is at a position of being able to get actually involved in the work, what is something today that anybody listening could do to take a step toward helping in this arena?

Andrew Hening: Absolutely. Well, first, yes, if you’d like to learn more about the work I’ve been doing and the resources, again, I’ve been trying to put out update maps and images from the book and everything, you can visit howtosolvehomelessness.org, and there’s a lot of information there that you can take a look at. In terms of how individual people can get involved, this is a question I get a lot and I think a lot about, what can people do? I would say two things. Number one is I would really encourage people to think about rather than what are the transactional things you can do, which are not a bad thing, like maybe serving a meal at a soup kitchen or these kind of one-time engagement opportunities, what are transformational things that you can do to really deeply change even one life? So, if you’re a business owner, can you consider hiring someone that maybe has a history of homelessness or has maybe challenges that have prevented them from getting a job?

Or if you own property and you’re a landlord, can you consider renting to people that maybe again, have these gaps in of rental history or other barriers that might be preventing them from coming back inside? Can you do those kind of things? Because even doing that for one person can be very dramatic. The other thing is just really follow your heart, because I believe that whatever your deepest natural passion is or your skills, lean into that.

So for example, I recently saw a performance from the Voices of Our City Choir, which is a singing group in San Diego that is comprised of people that are currently or formerly experiencing homelessness and listening to the co-founder of this group. And this group is now, I think, over 200 people that are part of this musical community. And listening to the co-founder, who was a jazz guitarist and a singer, she said the most powerful thing, which was, “I didn’t know what to do, but I needed to do something.” And what she did was lean into her gifts of music to create this incredible community, and they ended up going on America’s Got Talent, bringing on all this awareness around homelessness. So, I just think that’s such a powerful story of just follow your heart and try to do what resonates with you, and I guarantee that will help build community and help drive support for people experiencing homelessness.

Christin Thieme: I love it. Well, Andrew, thank you so much for sharing. Thank you for all the work that you’re doing.

Andrew Hening: Absolutely, it’s a real honor again. Thank you so much.

Additional resources:

- See how The Salvation Army fights homelessness.

- Find more information and resources from Andrew Hening at howtosolvehomelessness.org.

- You’ve probably seen the red kettles and thrift stores, and while we’re rightfully well known for both…The Salvation Army is so much more than red kettles and thrift stores. So who are we? What do we do? Where? Right this way for Salvation Army 101.

- Get on the list for Good Words from the Good Word and get a boost of inspiration in 1 minute a day with a daily affirmation from Scripture list this sent straight to your inbox. It’s an email to help you start your day with goodness.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.