Western Territory volunteer workers–officers, soldiers, cadets, advisory board members and others–have served in a variety of locations throughout New York City where The Salvation Army is providing caring assistance to families of victims, survivors, and disaster workers.

They began work shortly after the September 11 attack; they will continue as long as their help is needed. They bring not only willing hands, but loving hearts. Their compassion, it is said, is as valuable as the hot coffee and warm meals they serve.

Mike Patterson, North and South Carolina Division emergency disaster services, has observed that “People don’t just come to a canteen for food and coffee. They come for hope. They see someone in uniform and they know it’s OK…all is OK. They don’t even need to talk. They know The Salvation Army is here.”

Below are first-hand accounts and personal reflections from Western volunteers. They write of the tragedy and their role in bringing a measure of hope and healing to those affected by it.

AT GROUND ZERO

By Don Gilger, Major –

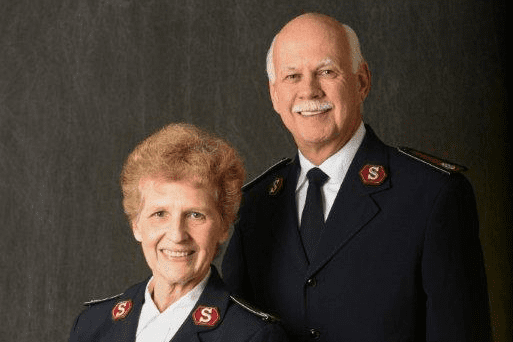

(Major Don Gilger and his wife, Ronda, serve as corps officers in Torrance, Calif.)

It’s hard to describe my two weeks at the “Florida kitchen,” site #1. The site was composed of three tents joined together where we fed thousands every day, in addition to providing medical and clothing needs. The WTC is a sensory experience. You feel it. You taste it. You see it. I divide it into three categories: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good

Silvanna is a corporate attorney on Wall Street who bills at $500 per hour–but she came every night from 5:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. and ran the food line. Her pay: the satisfaction of making a real difference in others’ lives. Mai is a paralegal whose firm was six blocks from ground zero. She was there for two weeks straight, using her vacation time to give back.

I worked with many religious organizations that supplied thousands of Bibles to those who came to be fed at our location. Never once did they complain about working the line, sweeping floors, emptying trash–they did it all to the glory of God.

I worked alongside many celebrities as well. They were so humble and would go and buy whole sections from supermarkets of the items we especially needed. Never did one look for publicity. “Thank you” was enough.

The other good memory is the cross that stands at the foot of ground zero. It overlooks this place of death as a reminder that love does conquer all!

The bad

The bad memories are of the loss. We saw the empty, hollow looks of those who lost loved ones September 11. No words or actions could bring them real comfort for the anger and confusion they felt. I saw the anguish of those who had no faith in God.

A man named Andrew came to ground zero to see the place where his wife died. They were married for nine years and he had kissed her good-bye on the morning of Sept. 11 and he never heard from her again. No funeral. No end. As we talked together, he admitted for the first time that she was dead. And the reality of this was more than he could stand. He had no faith in God. He was looking for answers. I could only offer him Christ, the one who has overcome death. When we began, he wanted nothing to do with God. In the end I prayed with him and he took a Bible to begin to read.

The ugly

The smell. It sticks with you. Never again will I smell smoke without thinking about ground zero. The ash. It falls all day, every day. The dust. It is on everything. We washed and wiped down the eating area every 10 minutes all day long. The sound. Everything was so loud. The generators were constantly running. The trucks rumbled by with debris. The body bags. They meant another death was to be confirmed and mourned.

The ugly memories stay with me in the early morning hours. I miss it and at the same time I hate it. Those contrasting feelings are the ones I take with me.

AT THE COMMAND CENTER

By Donna Jackson, Major –

(Major Donna Jackson, director of records and admissions at Crestmont College, served as personnel coordinator at the command center in Manhattan.)

Volunteers came from as far away as Germany–some had no connection to New York at all; others lost family members or friends when the World Trade Centers collapsed.

Some arrived at The Salvation Army WTC disaster command center from out of town and with no place to stay. “Regular” volunteers came in teams from colleges, churches, and companies–both local and distant. Each of the four U.S. territories and Canada sent teams of up to 16 officers, soldiers, employees and advisory board members. They came on a two-week rotation.

One stands out in my mind. Vincent began volunteering for the Army almost immediately after the attack. He came into the command center to be issued new identification and seemed a bit disoriented. I was reluctant to give him our ID until he shared that he “had to be there, had to help, had to do something.”

Vincent explained that his sister had died in the rubble when Tower Two crumbled. He had worked sixteen to eighteen hours a day as a way to work through his pain.

Although I worked at an administrative site, many people came just to talk, to share their grief, to weep. I spent time with a young man who had lost three cousins in the devastation. Not only was he grieving for them, he had lost his own father a year ago and a cousin-in-law (the husband of one of the three who died on September 11) earlier this year. The grief was raw but his faith in God was strong. He will be raising his cousin’s three-year-old child.

More than 800 were processed while I was the personnel coordinator. Whether they were New Yorkers or out-of-towners, the determination to serve in some capacity brought them together to be given identification and an assignment.

My two weeks at the command center were exhausting but very fulfilling. Working 12 to 14 hours days in a place where telephones never stopped ringing and people never ceased to mill about, brought its own challenge. Working with volunteers is not always easy. But God is gracious and gave me all that I needed strength, energy, a sense of humor, and a willing heart.

CRITICAL INCIDENT

STRESS COUNSELOR

(Major Cindy Lowcock served at the canteen on West Highway and Vesey St. in New York City; in the West, she is is senior counselor at Crestmont College)

Day One

I have seen it all physically today. Toured the perimeter of the site and then spent most of the day in “the pit” talking with firemen. They wait for some sign of human remains so they can hand dig the areas that the cranes cannot reach. I talked with firemen, policemen, construction workers, emergency medical technicians, morgue technicians, gas and electric workers. All with different stories to tell. I just listen. But I am not sure I hear them yet.

Day Two

Seemed like visitors day. Some were family members of those who died, but others were there to “look.” After hearing stories from those who were here on September 11 and witnessing the destruction, I feel angry about those who come here to see the horror. It is as if they are walking through someone’s funeral. I haven’t allowed myself to feel much of anything until now. I watch the few bodies (or body parts) that go by to the morgue each day, but it does not seem real.

Day Three

I spoke with a man who was in the Verizon phone building next to World Trade Center building six when the first plane hit Tower Two. He has been working 16-hour days for a month, getting phone lines functioning. I noticed as he told his story of how he ran from the building that it almost seemed rote, as if his feelings were still dull from the experience. Maybe being numb is one of the only ways people can cope right now.

Day Five

One month today (October 11); there was a prayer service this morning at the site. This is a world in itself and there is not enough time to think about much except getting the city up and running again. I want so much for the world to be normal again and yet I looked at the people around me on the subway tonight and felt confused about them being so “normal.” I look down on the dust residue on my once black shoes, and smell the mix of dirt, cement, smoke, and human remains on my “emergency” jacket. There is no normal here, but there are reminders of normal and I hold those snippets of life close.

Day Six

I took some pictures of the chairs that are scattered around the site. I am struck by the fact that on the morning of September 11, someone was sitting at their desk in one of these chairs, and another person sat enjoying one last cup of coffee. The people are gone….literally gone. When I get home I will try to remember to look at the people who sit in the chairs that fill my world and remember those who once sat in this World Trade Center world that no longer exists. Maybe then I can cry, but for now…it is the empty chairs that I see.

Day Seven

I sit waiting to go to the operations headquarters so that I can debrief and go home. I don’t feel like I want to stay. It is too overwhelming and progress is slow. I am a counselor; I have listened to the anger, observed the numbness, touched the sadness. I am a Salvation Army officer who has attempted to offer a cup of cold water and a message of hope in a tragic circumstance. I am a Christian who knows that God is bigger than any of what I have seen and heard, and he will remain here and go with me as I leave this place.

AT THE FLORIDA KITCHEN

Major Charles Gillies, Jr., Olympia, WA, corps officer, participated as the Army liaison with a team of four trauma counselors with Northwest Medical Teams International.

We headquartered at the Florida kitchen, composed of two-18 wheeler trucks fully outfitted as a kitchen and refrigerator site, with an air-inflated tent serving as a covered dining and refreshment area.

We went to listen to stories and support people in service. The stories we heard were heart-wrenching. One policeman asked a team member, “What do I tell my wife in supporting our friend? She got a call early the morning of the 11th from her 18-year-old son who worked above the 85th floor on Tower One. He said, ‘Mom, we’re on the roof. There’s a bunch of us here. Tell them to get a helicopter up here to get us off.’ Mom, realizing what was truly happening, kept him on the line. He said, ‘Mom, there is a lot of smoke coming. Get the copter here quickly…Mommy, the roof is melting…My feet are burning.’ And then the phone went dead. Now, what do we do?”

Our purpose in going was to engage in trauma counseling using the method characterized in everyday language as “dump and run.” We listened, took on the emotion and shock of the events, prayed with and for them, and separated, allowing the other to go on for a bit more time.