|

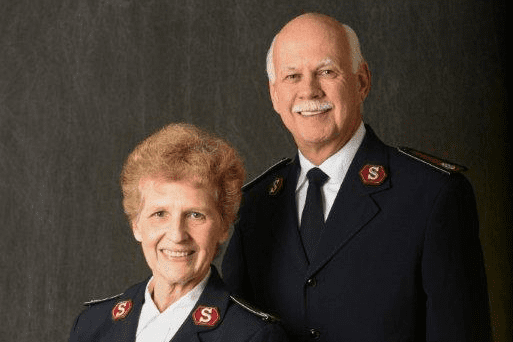

By Major Deborah Flagg –

Election ’96 is history, and if nothing else, it was good theater. All the elements were there: bracing dialogue, intergenerational conflicts, hints of scandal, intrigue in high places. It was also liberally doused with Hollywood: gala conventions, the star-studded elite, elaborate sets, catchy slogans and endless “spin doctoring.” Now, that’s entertainment! There were many candidates and many issues caught up in this frenzy, but our hopes and dreams seemed to polarize around two men, the men who would be king, both of whom at times appeared tragically flawed.

No doubt, the prospect of going to the polls to sort out the endless morass of proposals and politicos and finally register a decision left many Christians wanting to retire to a self-contained “biosphere” somewhere, singing all the way, “This world is not my home, I’m just a’ passin’ through . . .”

Yet, this world is very much our home. While we as Christians strive to live and move and have our being with God, it is in the context of a messy and muddled world that this relationship must be lived out. And, whether we like it or not, we are all political creatures. To paraphrase Wislawa Szymborska, poet laureate of Poland, our “genes have a political past, our skin a political tone, our eyes a political color. We walk with political steps on political ground.” Just looking at the root of the word tells us this. Polis is the Greek word for city–not just buildings and concrete, but people, citizens, community. We are all people, all citizens of somewhere.

In the musical Evita, a group of overly optimistic political types belt out with great gusto “Politics, the aaaart of the possible!” It’s comforting to think that the political process holds unlimited potential for needed change, but a quick look into the history books and today’s newspaper will tell us this is not so. Under the rubric of possibility, the questions emerge: “Just what is possible for Christians in the political arena in a pluralistic, post-Christian society?” How should we seek to create a space for God’s justice? What should we desire in the political sphere? Where and with whom should we align ourselves?

All of these questions bear careful and prayerful reflection and there are no easy answers. Few of us have an adequate theological framework through which our political concerns can be filtered and examined, yet we know that appropriate and Christianly engagement is a large component of our life of discipleship. Adding to our anxiety is the suspicion that in the political realm there is a large subterranean reality that we mere citizens are not privy to; there is a lot more going on than we are able to discern on the surface of things. Who can guide and speak the truth for us? What must we do to be “response-able?”

Competing Voices

Even within the context of evangelical Christianity, there are many differing views and voices. One of the most powerful voices in recent years comes from the Christian Coalition, whose executive director, Ralph Reed, describes himself as a “born activist and political operator.” Criticized for its close alliance with the Republican party, its ideological rather than evangelical stance, and an apparent preference for wealth, power and military might, the Christian Coalition, the “Religious Right,” has nevertheless become a very potent political force. Claiming to speak for God and for all evangelical Christians, the Religious Right has skillfully used the media to promote its very partisan political stance. Under the supervision of Pat Robertson, the platform has been so successful that in the minds of many people the word “Christian” is synonymous with this political power bloc.

The fact is, however, that there are other voices, equally Christian, coming from the “left,” the “center,” and other areas of the “right.” The evangelical publication Christianity Today quoted estimates that only one third of America’s evangelicals side with the Religious Right, another third would fall into the moderate or progressive categories, and another third are “unsure” where they fit. Despite the seemingly monolithic character of the Religious Right, there are alternative voices calling for a more inclusive, prophetic stance which moves beyond the old categories of “left” and “right.”

Chief among these voices is a faith-based group of political activists who have taken the name, “Call to Renewal.” With roots in some of the same evangelical territory as the Christian Coalition, this group includes and is endorsed by evangelical leaders from Philip Yancey and Tony Campolo to Roberta Hestenes. This national network of concerned evangelicals carries an important message: The moral and political issues facing our nation are too important to be left to only one voice. Seeking to replace “politicized religion” with prophetic faith, they invite everyone–left and right–to sit at the table of concerned dialogue, a table where new political visions might be born.

Richard Mouw, president of Fuller Theological Seminary articulates the need for this kind of dialogue in his book Political Evangelism: “If a commitment to dialogue and an attempt to foster and structure it within the Christian community can be seen as a necessary preparation for faithful political discipleship, we may begin to know God’s blessing on our attempts at political evangelism.”

Christ and Culture

These differing political approaches are current reflections of a debate that has been ongoing since the Church was established–what is the relationship between Christ and culture? In his book Christ and Culture, H. Richard Niebuhr offers a scheme for thinking about this theological dilemma. Believing that our politics determines our theology, he grouped church traditions along a continuum from “Christ Above Culture” to “Christ Against Culture.” Along this trajectory are the categories “Christ the Transformer of Culture” (St. Augustine, James Dobson and Ralph Reed would fit here) and “Christ and Culture in Paradox” (the Apostle Paul, Philip Yancey and Henri Nouwen would fit here).

These two categories are especially interesting because they seem to frame the current debate in evangelical circles (i.e. the Religious Right and the Call to Renewal). In looking at the dynamics of these two perspectives, the second option, “Christ and Culture in Paradox,” which simply says that both are authorities to be obeyed and that the believer must live within this tension, appears to be the more scripturally defensible.

We see this idea operative in the kingly succession and prophetic tradition of ancient Israel, whose monarchy was always partial and provisional. The activities and ideologies of the kings were always placed in tension with that of the prophets. The Hebrew prophets did not align themselves with the kings, or work to overthrow them, but stood “over against” kingly power, always applying the Words of God, always calling for righteousness and justice, always advocating for the widows and orphans. To make an unconditional commitment to an earthly king would have compromised the prophets’ unique position and silenced their prophetic voice.

Philip Yancey, in his book The Jesus I Never Knew observes that “History shows that when the church uses the tools of this world’s kingdom, it becomes as ineffectual or as tyrannical as any other power structure.” The New Testament writings of both Paul and Peter underscore this idea of “dual citizenship.” The Church’s identity comes from being a community, a polis, in this world but not of it, whose main task is to change lives not to change government. Our status as “resident aliens” is where our true power lies. We must constantly remind ourselves that the United States of America is not the Kingdom of God, nor will it ever be, but it is a place where people of faith can articulate what the Kingdom of God looks like.

The Politics of Jesus

The politics of Jesus coalesce into a symbol, the ultimate symbol of self-giving love–the cross. His is not the politics of coercion or power, but a politics of compassion which cuts across all lines and barriers with extravagant grace, giving special attention to the sinful, the weak, the poor. Jesus’ primary purpose was not to pass laws or write a new theology, but to form a community of redemption and love through which the voice of God might be heard in the world. To again quote Yancey’s insightful book, “If a century from now all that historians can say about evangelicals of the 1990s is that they stood for family values, then we will have failed the mission Jesus gave us to accomplish: to communicate God’s reconciling love to sinners.”

Rejecting both a proud triumphalism and a passive withdrawal, Jesus’ stories describe the Kingdom as a “secret force” that works from within: seeds, yeast, salt. All of these elements have a subversive quality that honors and preserves their home substance while engendering growth and life through their very presence. It seems that Jesus’ political platform can be summed up in these two statements: “My kingdom is not of this world,” and “All people will know you are my disciples if you love one another.”

The Church and the World

As the Church, we are called to be “creatively maladjusted.” The Church as ekklesia is made up of those who have been called out of the world for citizenship in another kingdom, and the primary political function of the Church is simply to be the Church, a place where God’s love provides the glue and people can grow up into true discipleship. As Eugene Peterson says, “What the world really needs is a few saints.”

Part of our “saintly” task is to be involved in the world and to respond Christianly to the issues of our time as those who came before us responded to the issues of slavery, child labor and the subjugation of women. We are called to enter into the public discourse not with rancor or condemnation, but with compassion. To really make this work, we must first be a people of repentance.

In a letter written in 1944, Dietrich Bonhoeffer asked the question of his Church, “Who is Jesus Christ for us today?” His question must also be our question. What are we–the Church in the late 20th century–doing with Jesus? What are we allowing Jesus to do with us, to teach us? Another question we must ask comes from H. Richard Niebuhr in his essay, The Question of the Church: “What must we do to be saved?”

It is only by dealing with these questions on a daily basis that we will be able to make a difference in the world and offer people healing, hope and transformation. It is only through a life of obedience to God that we will be able to work on behalf of others and speak a prophetic word without the need to reinforce ourselves with a rigid fundamentalism that creates division rather than unity. It is only through God’s re-ordering of our hearts that we will be able to dialogue with and respect those who don’t think like we do.

After dealing with these questions and many others, after listening to many voices, what do we say about God and country? The author Flannery O’Connor assessed our situation this way: “The Church can make a difference; but it cannot kill the age.” We cannot make everyone Christian by passing laws or any other means; only God can do that and obviously he has chosen not to. Politically, we live in the “now and not yet” of God’s Kingdom. What we can do, however, is be faithful, and that counts for a lot.

In thinking Christianly about politics, perhaps a good place to start is here: Because the Church belongs to God our political mandate is this–Remember that no human enterprise is free from sin. Never be comfortable with conventional definitions of power. Never wholly embrace any earthly king. Love one another.