National Advisory Organizations Conference 2007

A summary of Jim Collins NAOC remarks

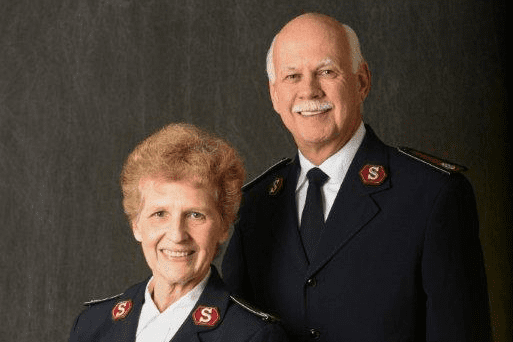

Commissioner Israel L. Gaither presents a certificate of appreciation to Charlotte Anderson as Commissioner Maxwell Feener looks on. |

I am delighted even passionate to be here with you. It’s a privilege.

I’ve spent my adult life to date studying the difference between great companies and good companies and why some become great and others don’t; why some sustain it and others don’t. But even after nearly two decades of research into the business sector, I have come to believe passionately that if we only have great companies, if we only have a great business sector we will merely have a prosperous nation. We will not have a great nation. To be a truly great nation, we must also have great K-12 education, and great symphony orchestras and great government agencies and police departments and homeless centers and universities, health care, cause driven non-profits and of course great movements like The Salvation Army.

I come to you today not as an expert, but as a student. I come to you to share with you some of what we’ve learned – about how the difference between great and good comes to life through the lens of the social sectors. I do this in hope that you might carry some of these ideas back with you into your communities to build an even greater movement. And that’s what I’ve come to learn in my brief study of The Salvation Army: it’s not an organization – it is a movement. And it is a movement that has now got 142 years of building momentum. It’s a nice start.

Perhaps the single biggest lesson from our work is that greatness is not a function of circumstance. It is a function first and foremost of conscious choice. We are not imprisoned by our circumstances—we are freed by our choices and by our disciplines. I do not see myself as an expert on The Salvation Army and it would be arrogant and presumptuous of me to pretend that I know you better than you know yourselves. As I mentioned I am both a student of The Salvation Army and the social sectors in general. My aim today is not to say that the secret is for The Salvation Army to run itself more like a business. In fact, I would like to suggest that business has as much to learn from the social sectors as the other way around.

I had a conversation with Bob Watson to discuss his book, The Most Effective Organization in the U.S. In preparation for this event he graciously spent an hour with me on the phone. And he told me a story of visiting Peter Drucker when he was beginning to work on the book. His first draft of the book spoke toward folks in the social sector. Peter Drucker, in his typical Druckarian way said: “You have got it backwards. You should position this for businesses to learn from The Salvation Army.” There is no hierarchy of effective organizations with business at the top. The critical distinction is not the difference between business and social sectors but the difference between great and good.

A culture of discipline

A culture of discipline, disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and take disciplined action is not purely a business construct nor is it purely a social construct—it is a greatness construct. You will find it wherever you find sustained great results. You will find it in great companies, and you will find it in great social movements like The Salvation Army.

Notice the order? Disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought who take disciplined action. We’ve learned in our research that the order is important. We found in our analysis of what separated great companies from good ones that the ones who went from good to great were led by people who thought first about who and then about what. They thought first about who should be on the bus, who should be in what seats and sometimes perhaps who might need to get off the bus—and then they thought about where to drive the bus. When they focused on getting the right people on the bus and the right people in key seats and then figured out where to drive the bus, they were able to deal with whatever the world threw at them. They had an ultimate hedge against uncertainty. It’s not your plans but your people.

Shifting engines

Later I’m going to talk about one of the differences between the business and the social sector, which is the shift from an economic engine to a resource engine. Especially in the social sectors, the most important element in the resource engine is not money. It is people. It is time. Maybe your greatest gift is the offer you make to people — that they would have the chance to serve, to be of service, to be of use. How do you change the world? Perhaps you don’t. You change people. They change the world.

The younger generation, a valuable resource, is very passionate about wanting to serve. They need a vehicle. And so, I give you one of my first questions today. How can you increase and track your ability to begin to integrate into your great movement that next young generation? They are the future. How are you doing at that? Are you relevant to them? Are you their choice for a vehicle of how to exercise their passionate, desperate desire to serve?

Qualities of effective leadership

I’d like to talk a little bit about something that was very surprising in our work—about the types of leadership that seemed to produce the best results. We selected our companies based on purely empirical data driven results—financial cumulative stock returns relative to the general market. You could not find a more clinical selection variable, a more purely financial variable. Some leaders in those companies prevailed, and some didn’t.

We found something different there—something distinctive—something special, a qualifier in the great companies. It was a great and delightful surprise. These had to be some of the greatest chief executives in the history of the Fortune 500, and what was their signature? It wasn’t towering charisma. It wasn’t their great presence. No—it was humility. The distinctive signature of the greatest chief executives we studied in the history of the Fortune 500 selected on a purely financial basis was humility. We weren’t looking for this. And yet you find something that deeply resonates with spiritual and human teachings

But it is humility of the very special type. It is a humility that I think you in the Army might understand at a deep core level. It is humility defined as absolute burning, passionate ambition—not for themselves but for the cause. That humility combined with a stoic will to do absolutely whatever it takes, within the bounds of core values. Humility and will combined is a very powerful package.

In my small studenthood of The Salvation Army I was struck by a story in General Shaw Clifton’s book, Who are These Salvationists, where he tells the story of an event in England in 1914, when the first World War broke out. England was being strangled by U-boats and bakers began raising prices on bread. General Bramwell Booth arranged a meeting with the bakers and asked them to drop their prices. He was very gracious, but the prices did not come down. So, he very quietly asked again. They still did not come down. In a third meeting, very calmly, he said: “If you do not bring down the prices so the poor can eat, we will open up Salvationist bakeries and undercut you.” Prices came down. Ambition—Cause— Will. It is only when you combine the humility with the will—the stoic will—that you truly achieve greatness.

As we’ve studied in the business and social sectors, we’ve found that there are actually two types of great leadership; one I describe as executive. We find this type in the business sector. It has concentrated executive power. In the social sectors, there’s rarely concentrated power. Sometimes it’s “One hundred points of no.” There is, then, what I describe as legislative leadership. These leaders can design the conditions for the right decisions to happen even though they themselves do not have the individual power to make a decision and often face negative points of power that can stop things from happening. One thing that we’ve learned, when we step into a social sector in a diffused power environment—a power based on humility and will becomes even more important. Negative power is very real. Therefore, the trump card is that people have to believe and know deep down that you’re in it for the cause—not for yourself.

The Stockdale paradox

Disciplined people with disciplined thought and disciplined action—I did some reading on you folks about the power and applicability of one of the key findings that came from good to great. It’s a finding that we came to call the “Stockdale paradox.” I would like to share with you the Stockdale paradox through the story of my interactions with one of the most remarkable men I’ve ever met, a man named Admiral Jim Stockdale. Admiral Stockdale was the highest-ranking military officer of the Hanoi Hilton when he was shot down over Vietnam in 1967. He was in there for seven years—from 1967 to 1974—and was tortured over 20 times. In preparation for a day that I got to spend with Admiral Stockdale, I read his book, In Love and War, and as I read I found myself getting depressed because there seemed to be no end in sight; there was no guarantee he would get out or that he would ever reunite with his family.

I asked him, “Admiral Stockdale how, how did you not get crushed by the experience? How did you deal with the depression of not knowing the end of the story?”

“Oh you have to realize,” he said, “I was never depressed, it never got the best of me because I never ever wavered in my faith that not only would I get out but I would turn this into the defining event of my life. That, in retrospect, I would not trade.”

After a long pause I said, “Admiral Stockdale, who didn’t make it out as strong as you?”

“Oh that’s easy,” he said. “It was the optimists.”

“I am extraordinarily confused; you sounded very optimistic.”

“They were the ones who always thought we would be out by Christmas and Christmas would come and go. And then they thought we would be out by Easter and it would come and go. And then Thanksgiving and it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

And that is when Admiral Stockdale taught me the lesson. He grabbed me by the shoulders and said, “This is what I learned. You must never ever confuse the need for absolute unwavering faith on the one hand with the need on the other hand, simultaneously, to confront the most brutal facts. We’re not getting out of here by Christmas.”

That is the Stockdale paradox. We found in all of our companies that prevailed in contrast to those that didn’t, they had that Stockdale paradox. And it strikes me that The Salvation Army is founded on the Stockdale paradox in some way going all the way back to this unwavering faith and confronting brutal facts. In 1865 Booth took his work right into the teeth of the brutal facts in east London. We must confront the facts. As a person, I must confront the brutal facts about myself and my ability to confront today’s challenges—adults with substance abuse problems, chronic homelessness, aftermath of tragic catastrophes —tsunamis, hurricanes, and someday earthquakes that we face in this country. If we loose unwavering faith we’re doomed. If we fail to confront the brutal facts we’re doomed.

Confronting the brutal facts means that the best social sector institutions and the best social sector leaders track the facts—track the data—they are really relentless about determining what the facts say about how we’re doing and what the facts say about what we face.

Inputs and outputs

One of the primary differences between the business and the social sectors—in business, money is both input and an output. Money is both a means to success and a definition of success. And there can be a great temptation then to come into the social sector organizations and to try to define success purely in financial terms because it’s what we know how to do. I encourage you to be careful. Because the key to success in the social sector is to know the difference between inputs and outputs. In the social sector, money is not an output it is only an input. Rehabilitated alcoholics might be an output. People who give themselves over to a life of faith might be an output. Children who get a better start in life than they might otherwise might be an output.

Revenue is an input. Funding is an input. And the thing that a great social sector does is to ask ourselves: “What are the inputs and what are the outputs?’ Then, we hold ourselves permanently accountable for improving output results. When you return to your communities, carry this question—What in our community do we mean by great results? Are we improving? If not, why not? And how can we improve any faster in relation to our audacious output goals? It strikes me, that at a national level there are some very interesting questions on the table concerning whether or not we work to elevate results. Do we begin to think about not just addressing symptoms but addressing root causes so that results might generate continued improvement, and, if so, which results are they, and what makes it happen?

The “flywheel effect”

Disciplined people, disciplined thought and disciplined action in the social sectors means understanding that in any great institution there’s what we came to call a “flywheel effect.” This means being resolutely clear about what you’re passionate about, deeply in your mission, realizing what you can contribute that no one else can, and knowing what best drives your resource engine. By remaining relentlessly focused on that you begin to build this giant momentum like a flywheel turning and turning and turning and going from 10 to 100 to 1000 to 1 million turns in that flywheel.

In business it’s so easy to get the flywheel going because of the money being both an input and an output. In the social sectors that link between profitability and rational capital markets does not exist. So how does the flywheel turn? I’d like to suggest that we must shift from an economic engine, driven by profit, to a resource engine that has three parts: time, access to the right people—willing to give themselves over to what you are trying to do— and money. Most importantly, however, in the social sectors is brand reputation.

You attract believers. You build strength. You demonstrate results. These results build the brand which increases results, which enhances the brand which allows you to attract believers, build strength and demonstrate results at a higher level. This allows you to further build a brand and attract more believers. And the flywheel goes round and round and round. What that means is that in all corners of every community, The Salvation Army brand must be protected at all costs.

To do lists

Disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and disciplined action—I would like to suggest that those that I’ve met in the social sectors who are so passionate about what they do and have such a desire to do more demands that I ask a question: How many people in this room have a “to-do list?” Yes, all of us have some degree of being productively neurotic. How many of you have a “stop-doing list?”

The presence of a to-do list without a corresponding stop-doing list is a lack of disciplined action. If you’re going to add a priority, you must have a priority to stop-doing something. But that’s so hard in the social sectors because there’s so many to-dos that could make a difference. I will leave it up to you to resolve the existential dilemma of putting a stop-doing list on your next to-do list.

Now, I would like you to carry back to your communities this question: “What must we have the discipline to stop doing? What is not delivering results?” We hate to confront the brutal fact that it is not delivering results. What does not fit our mission? What does not fit what we can distinctively contribute? What might not contribute to the brand? What might erode the brand? What must we stop doing? For building momentum, the key is consistency over time. And of course, as I have learned a little bit about you folks, I have noticed how over time there has been clarity about not only what to do but about what not to do. Notice how in the mission statement itself, there is a statement of what not to do. “Without discrimination.” We will not discriminate who receives our service based on their faith, or their background or their circumstance. We will not take sides during war time. We will not become the tool of any political party or politicized issue. We will not make the needy come to us. We will go to them. We will not compromise our theological mission for the sake of funding.

Going from great to good

We have now studied nearly 40 companies over their history that never became great, that squandered great promise or that fell from great to good. I’m writing a book now on the inverse of from good to great. How does that happen? How does the infection of mediocrity creep into something that is exceptional?

I’d like to offer you two points that tie into this process. First, almost all decline is self-inflicted and can be avoided. Institutions, great institutions, do not fall because of what happens to them—they fall because of what they do to themselves. Second, you would think that companies lose their greatness because they somehow become complacent, they become lazy, they refuse to change and the world passes them by because they didn’t change enough. And yes of course, in competitive markets, if you do become complacent, if you do become lazy, if you do become fat and happy and refuse to change, the world will pass you by. But it turns out that that’s not generally the pattern of what happens. Almost all the companies that fell from great to good were anything but complacent. One of them fell during the very time they were introducing a new product every single day, 365 days a year. This is not complacency. The signature of mediocrity is not an unwillingness to change. They often change too much the wrong things. The signature of mediocrity is chronic inconsistency. I believe this is especially true in the social sectors. Drifting under pressure, drifting in pursuit of opportunity, drifting in pursuit of funding, from your core values and from your mission and from your unapologetic allegiance to your mission would be your greatest danger. Yes you must change. But you must change with great care that increases— increases—consistency with your mission.

Embracing the genius of the “and”

One of the key ideas from our research is what we came to call the “genius of the and.” When we studied companies that were built to last over time, companies that prevailed over long periods of history, we found that they were and organizations not or organizations. Embracing the “genius of the and” is not trying to find a balance between two forces. No—it is the opposite. It is about embracing two sides of a coin equally, obsessively at the same time—this is the genius of the and. Is it pragmatism or idealism? No! It’s pragmatism and idealism. Theological mission or social work? Theological mission and social work. Good intentions or results? Good intentions and results. Faith or deeds? Faith and deeds.

In our work we found that behind any sort of long-lasting institution that does exceptionally well is one giant and, two sides of a coin that play at the same time. Think of it as preserve something core and stimulate progress. Preserve and provide continuity on values that must remain fixed, that must not be compromised, and being open to changing practices and strategies and traditions still consistent with the core values. Preserve the core and stimulate progress. Hold firm to what we stand for and be thoughtful about how we do things. We hold these truths to be self evident. We lose our values, we lose our soul. We lose our soul, we lose it all. And yet the world changes. And so the great duality is this tension between what is core and what is open for change. We face a world in dramatic change—the demographic shift away from the WWII generation that has been a key source of funding, to the baby boomers, to this next wonderful glorious young generation. We face frenetic waves that overrun us—cell phones, email and over information. We face a world increasingly fearful—a world increasingly split into devices—debate amplified by 24-hour media. “If you disagree with me, you’re evil.” That is dangerous. Preserve the core values and ask how must the practices change.

My sense, as a limited early student in your development is that The Salvation Army is at an inflexion point where there is tension and pressure on core versus practices. Which practices and traditions should remain and which should evolve without ever compromising the core? And this is the crux tension to embrace intelligently as disciplined people, with disciplined thought and disciplined action.

Core values and practices and

traditions—knowing the difference

The key challenge, I might suggest, is knowing the difference between the core values and the practices and traditions. And here is what we have learned, we have been studying companies that have prevailed in highly disruptive industries. We’ve been doing this as a new piece of research, where the companies are surrounded by highly turbulent environments, where the world around them is changing tremendously. Guess what we have learned—they constantly challenge but rarely change their distinctive disciplines, their distinctive practices that make them special. If I walked in here next year and you said, “By the way, we decided to give up uniforms, our system of ranks, decentralized structure, our officers only being married to other officers—because the world is changing and we thought we had to change a whole lot in one year to keep up,” I would be worried. And yet at the same time if I came back in 10 years and everything was exactly the same, I would also be worried.

And so I issue you a challenge, I issue you this question: As the pressures of the world bear down on you, as the world becomes increasingly turbulent, uncertain, fast moving, where are the key grinding points between the eternal enduring core values of The Salvation Army and the practices, and which practices need to evolve and which must we hold to for now? I have asked this question. It is for you now to answer.

The secret to it all is to realize you’re always only good relative to what you can do next. And so I remind you of that statement—142 years is a nice start.

One of my students at the Stanford Business School—a young man from South Africa, told me: “I am wealthy—I have a purpose for my life.” Since then I have seen many of my former students struggling with the question: What does it all add up to? Have I been of any use? And that is I suspect one of the secrets to The Salvation Army. By tapping the desperate craving for meaning and providing a clean path that delivers real results, the Army gives millions of individuals answers to the question. How can I find transcendent purpose and how can I be of use? No matter how much the world changes, I might suggest that this is an infinitely renewable source.

A personal Board of Directors

Good is the enemy of great. I believe that this great society of abundance in which most of us are so privileged to live—many if not most, will get to the end of their lives and have to accept the horrifying truth when the clock is running out that they did not have a good life. Because they just principally went for the good life. Good is the enemy of great.

I would like to challenge each of you to think about how you can take some of these ideas back into your work and communities, back into your own life. Business people talk about “governance.” What about personal governance? Have you built a personal board of directors, of wise elders who you would never want to let down?

There are two approaches to life. There are those who go at life as a series of transactions and there are those who go at life as enduring relationships. In any movement, it is all about relationships and not transactions. In a life, transactions can never provide meaning. Let me share with you something one of my personal board members impressed upon me. John Gardner, a former secretary of Health Education and Welfare during the Johnson administration and senior faculty member at Stanford, brought me into his office one day when I was still a junior faculty member. He said, “Jim it occurs to me you spend way too much time trying to be interesting. Why don’t you invest more time being interested.” I learned that disciplined thought and that being of use, perhaps as a board member or somebody contributing, doesn’t mean that you have to come in with answers. It means coming in with questions.The Stockdale paradox not only applies to organizations. It also applies to individuals.

I mean seriously the challenge I left you with concerning the inflexion point and tensions between values and practices. I challenge you to go back to your communities renewed to ask the question: Where are the tension points on our practices and how is that different from our values so we can hold our values and be intelligent about the evolution of our practices?

And I will close with the words that Peter Drucker left ringing in my ears because they are so appropriate to where you are and what you do. As we were sitting in the car at the end of a day together, he slammed his arm down on the armrest as we were getting ready to go and he turned to me and said: “Now Mr. Collins, please—please do me a favor. Go out and make yourself useful.” And I realized something, that what he was saying is that perhaps the greatest gift we can give ourselves is to make ourselves useful. And it seems to me that that is what you are all about—a movement that allows people to plug in and to make themselves useful. And so I leave you with Peter Drucker’s admonition ringing in your ears. “Now please, go out and make yourselves useful.”

Thank you.