As shut-off notices and delinquent bills still haunt Flint, Michigan, residents, The Salvation Army works to give them some breathing room.

By Lizeth Beltran –

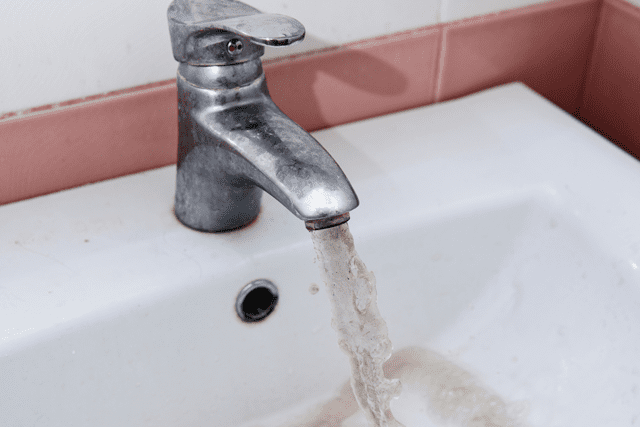

Cynthia Haynes boiled her tap water each night, ridding herself of any and all bacteria and potential health hazards—or so she thought.

“They never said there was lead in the water,” said Haynes, a 47-year-old mother in Flint, Michigan. “All they were telling us at first is that there was bacteria and to just boil it.”

Haynes, whose 7-year-old son falls on the autism spectrum, said she never thought lead poisoning would affect her family. Her son, who battles sensory issues, is very particular about his diet, but there is one food he loves—noodles.

“We don’t really drink water, so with me making the noodles, I’m boiling the water and thinking it’s clearing out the bacteria,” she said. Haynes noticed drastic changes in her son following 2014, when the city switched its main water supply to the Flint River.

“His behavior was getting out of control,” Haynes said. “His behavior has always been different because of his autism, but now it’s really bad—especially at school.”

Just one year ago, Haynes had her son tested for lead poisoning and the results came back positive. His Blood Lead Level (BLL) was 5.6.

According to the World Health Organization, lead affects children’s brain development resulting in reduced intelligence quotient (IQ), behavioral changes such as reduced attention span, increased antisocial behavior, and reduced educational attainment. Lead exposure also causes anaemia, hypertension, renal impairment, immunotoxicity and toxicity to the reproductive organs. Some experts say the neurological and behavioral effects of lead are irreversible.

The challenges and stress of raising a young child on the autism spectrum is difficult enough, and for Haynes, any help from community organizations is more than welcome. She is currently in the process of receiving assistance from The Genesee County Salvation Army with past due bills and car repairs.

The Salvation Army has played a large part in assisting residents throughout the water crisis, partnering with community organizations in hope of restoring some faith in Flint residents. The Salvation Army’s current focus is helping those with delinquent and shut-off notices pay their bills and avoid being displaced.

Although the state had initially provided credits to residents in Flint, covering two-thirds of their bills, a recent announcement by the state declared credits will only be offered until the end of February 2017, leaving many without viable options to pay their bills.

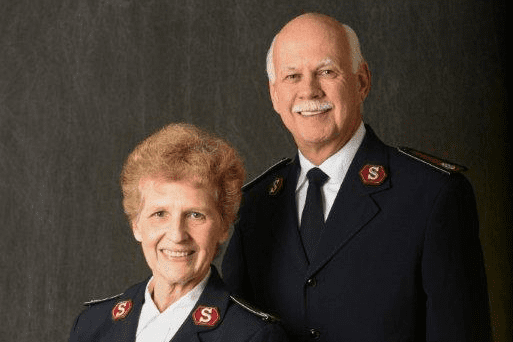

“They starting sending shut-off bills to individual homes, because several have not paid their water bill, even their sewer bill, along with other things because of the water crisis,” said Captain Caleb Senn, Genesee County Coordinator for The Salvation Army. “So now we have some funding both from the water crisis funds, as well as United Way gave us a grant, to help pay down those water bills.”

Senn said one of the ways The Salvation Army has adapted its service to the water crisis was change the entire structure of its system.

“We help so many people in our social services offices with rent, mortgage, utilities…with the water crisis—that all had to be redesigned,” Senn said. “When people come to us now, needing essentials for water and needing their bill paid, we have a totally different system where they walk in and are able to see someone almost immediately.”

The Salvation Army has also stepped up in other ways. Last year, from January to April, the Army served 5,000 meals to residents of Flint. They also held a Picnic in the Park program during the summer to ensure kids have nutritious meals.

“We want to make sure kids in this area have good nutrition because all the research states that good nutrition is essential when there’s been lead in the system,” Senn said.

Of course, ensuring access to safe water remains the top priority.

“There has been a program by the city that hires people to go door-to-door and ensure people have filters or access to filters, ” Senn said. “We’re not part of the program but we have our caseworkers to see if they can get jobs doing this.”

Door-to-door services allow those who are homebound and less mobile to gain access to safe water. Other community organizations for disabled residents have a disabilities network that addresses the needs of this population.

Yet, according to Kathi Horton, president of the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, the toughest challenge ahead is addressing many residents’ fundamental dissolution of trust.

The Community Foundation will be constructing a new early childhood center for infants, toddlers and preschoolers that will be in service full-time. The center will provide an early childhood program, a space for adult literacy with a two-generation approach, and a model place for early childhood educators, where they can come and observe high-quality curriculum development. It’s not a panacea, but rather an encouraging step forward.

“Even though the state and city have made some almost herculean efforts to address the water crisis issue,” Horton said, “[the water crisis] was so devastating for people at a fundamental level.”

Listen to this article