An excerpt from Soldiers of Uncommon Valor: The history of Salvationists of African descent in the United States

An excerpt from Soldiers of Uncommon Valor: The history of Salvationists of African descent in the United States

By Warren L. Maye –

In the midst of the most racially turbulent period in United States history, black commissioned officers of The Salvation Army’s USA Eastern Territory convened a special meeting to discuss race relations within the organization. The first of its kind in The Salvation Army’s history, the meeting served to unite the voices of black officers concerning important issues.

However, some Salvationists voiced opposition to such a meeting. In response, these black officers persuaded Army leadership that their intention was to bring down the walls of separation between themselves and the larger Salvation Army community, rather than become “separatists” or “isolationists.” Eventually, visionary Army leaders granted these officers permission to convene for the purpose of assessing their future in The Salvation Army.

The meeting had the enthusiastic support of Army leaders such as then Territorial Commander Commissioner Edward Carey, Colonel J. Clyde Cox, Lt. Colonel John Waldron, and then Divisional Commander Brigadier Charles Southwood.

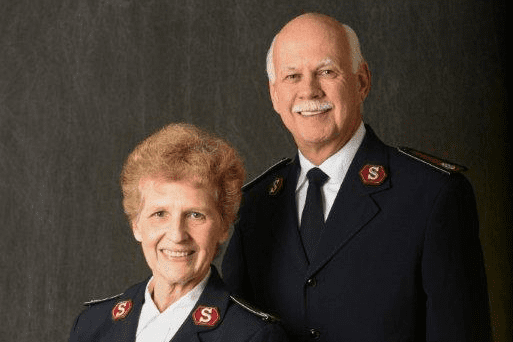

Captain Israel L. Gaither, who was then one of the officers responsible for planning the assembly and who later served as National Commander of the Army in the U.S. from 2006-2010, wrote that it would encourage the implementation of ideas and raise expectations for future gatherings. The officers laid plans to publish a candidate recruitment brochure and suggested the Army hold a territory-wide forum with black youth on opportunities in The Salvation Army.

“We are turning an important corner as far as Negro recruitment for officership is concerned and I am anxious that the flow of [blacks], especially young people in the ranks, will increase,” Gaither wrote.

Some critics were still concerned that the black officers would later demand that the Army set up a “black division” within its ranks and become separatists or isolationists. However, level heads prevailed. Brigadier B. Barton McIntyre, then divisional secretary for the Metropolitan New York Division and a black officer, wrote to Cox with assurance that black officers “…did not want be interpreted as a splinter group…”; rather, they were making an “…honest attempt within The Salvation Army framework to define objectives, expand relationships, and improve the general image of the Army in community services and opportunity. This is not to be interpreted in any way as separation,” he wrote.

The long-range effect of this meeting was to force Salvation Army leadership to recognize its dual ministry to black officers and to the broader black community served by the Army. Black officers held subsequent meetings and forums, which led to the formation of a Multicultural Department in the East.

The hope was that young black Salvationists, disappointed thus far by the lack of opportunity, would be encouraged by watching their parents secure a better future when black officers would be able to play an influential role in shaping Army administration. The black officers recommended that the Army devise new and effective methods to promote opportunities for service in the Army to blacks by:

- Using posters, pamphlets, “specialing” groups, radio, and television

- Adapting to its promotion campaign music that would be meaningful to all worshippers both black and white

- Appointing black “specials” and inviting them to conduct weekend meetings at various corps, corps cadet rallies, or councils, and at camp meetings

- Appointing black officers to the School for Officer Training staff

- Preparing black officers for specific leadership positions

- Introducing courses in black history, cooking, grooming, special music, clarinets, drums, and other programs relevant to the black community into Girl Guards, Boy Scouts, and young people’s events

- Devising methods at the corps and territorial level whereby soldiers from the Caribbean and corps nearest their residence or workplace could have communication with their home territories

- Appointing a minority coordinator with department head status to serve at territorial headquarters

- Submitting a proposal to the territorial commander requesting that black officers meet periodically for a full-day workshop in a central location in the territory

The group also addressed longstanding cultural issues prevalent among black Salvationists. For instance, Caribbean officers typically found acceptance from whites more easily than did African-American officers. At the meeting, officers raised this issue and recommended that the Army spend more effort on developing black officers from the United States as well as tapping the Caribbean for “reinforcements” [new officers].

However, such a task required that the Army first reconcile its internal differences and find ways to effectively bridge social and cultural gaps with the African-American community. According to one black leader of the day, the Army’s tendency to embrace a neutral position on civil rights was an obstacle to achieving such reconciliation. The leader agreed with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had called the behavior of white moderates “the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom.”

The Salvation Army of 1969 had changed since its radical days under Founder William Booth’s leadership. Rather than engage in acts of civil disobedience, the Army opted to remain silent in most cases, even in the midst of an unjust status quo. Most men and women wearing the uniform were subdued rather than display the indomitable spirit of such legendary figures as Booth, who despite threats from the authorities, had protested in the street against the mistreatment and abuse of women and children workers in poisonous London match factories; or Joe the Turk in the United States, who had frequently endured the humiliation of incarceration for the sake of spreading the Gospel message. Although the Army supported the goals of civil rights in principle, it stopped short of officially supporting the radical means being used to achieve those goals.

Yet, Army administration did carry out several recommendations from the black officers’ meeting, such as allowing them to hold subsequent conferences and to convene forums on candidate recruitment. But the Army’s social fabric was still tightly stitched to the larger segregation-oriented society. Black officers continued to command only black corps, while white officers enjoyed more varied ministry opportunities.

_____________________

This is an excerpt from “Change from within,” a chapter in Warren L. Maye’s Soldiers of Uncommon Valor: The history of Salvationists of African descent in the United States (Others Press, 2008). Find more in his book including black Salvationists’ attack on racial stigma, a Salvation Army-issued statement on “racial justice,” and details of inner-city ministries in the 1970s-80s. To order, call the Eastern Territory’s Trade Department at 888 488-4882.