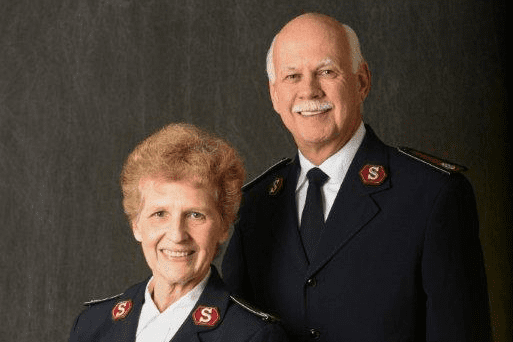

By Gordon Bingham –

Territorial Social Services Secretary

Sixty years ago the federal government established a “safety net” for the most vulnerable persons in our nation: the aged, the blind and disabled, and mothers with children. Assistance to these persons was to be guaranteed through a series of categorical programs: Old Age Assistance; Aid to the Disabled; Aid to the Blind; and Aid to Dependent Children, which became Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC. All but AFDC were later folded into a new program, Supplemental Security Income, or SSI.

The AFDC program was the primary target of the recent “Welfare Reform” legislation, and the single program which most people have long identified as “welfare.” It is a program that no one has liked very much, not liberals, and certainly not conservatives. Aimed originally and principally at helping widows and orphans, it has had the unintended consequence of contributing to the growth of single parenthood, and has helped foster a “culture of dependency.”

The arguments surrounding the passage of this legislation echo the themes of William Booth’s time: Are individuals personally responsible for poverty, or are they victims of shortcomings of our economic and social systems? How can people be given a helping hand without making them dependent? Who is responsible for the poor, and who can best help them–government? or private charity? The “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996,” or, “Welfare Reform,” stitches together a new response to these questions, reflected in its title.

The primary elements are simple: to restrict access to assistance on the part of those presumably able to work and support themselves; and to move responsibility for assistance from the federal level to the state level. Supporters of the latter envision 50 state “experiments” in getting people off welfare and back to work. Others see a competition between states to see which can be the most restrictive or punitive.

The logic of this legislation assumes that if welfare is simply unavailable, people will then find employment and the health and self-respect that comes with this. This may be no more valid than the assumption of Booth’s day that if welfare were made sufficiently unattractive, i.e., if those in need had no recourse but to submit themselves to the “workhouse,” people would be motivated to take care of themselves. A number of hurdles exist between many of those now supported by welfare and successful employment. The serious questions as to the availability of jobs and/or access to child care, affordable housing, transportation and other supports, have yet to be fully addressed.

The individualized state approaches to welfare, coupled with specific cutbacks to other programs, e.g. an across the board three percent reduction in food stamp grants, and the elimination of assistance to immigrants, suggest increasing numbers of people in need seeking help through Salvation Army and other private resources.

We can anticipate the need to maintain and, where feasible, to increase our food pantry and feeding programs. These have been growing almost continuously since 1980, responding to chronic food crises among the homeless and those with limited resources.

The mandate to move from welfare to employment suggests we look for means to increase programs of family support: educational and job training efforts; case management and counseling; all kinds of childcare, but especially before and after school care; and support groups where those impacted by these changes can share resources and develop mutual, self-help skills. There will be no easy transition of those who have become dependent on welfare into viable and sustained employment.

Other features of this legislation appear intended to foster a continuing “partnership” between government and private charity. We will need to strategize as to how best to position ourselves with regard to state initiatives if we are to be a continuing participant.

To that end the Territorial Social Services Department will convene one or more mini-conferences in the fall to examine the impact of the welfare reform act on our programs and to consider a strategic response. As we continue to assess the implications of this legislation for our work, it may be useful to recall that in every instance in the past where Salvation Army help to people has been questioned on the grounds of whether the individuals in need were “deserving” of our help, e.g. striking workers, illegal immigrants, etc. the operative principle has been to respond to the need for its own sake.

We continue to believe a loving response to the need as presented will open the door not only to other kinds of more substantive help, but to the ultimate rehabilitation of new life in Christ.

The welfare reform legislation will present us with new challenges and doubtless much frustration. It is also an opportunity to realize the integrated ministry of the Army. We must look at it in that light.