The Salvation Army adopts a protocol for more programs to implement and administer the life-saving overdose antidote.

By Jared McKiernan –

Eric Owings took the company truck, but it wasn’t a business trip—he was on his way to buy some heroin.

“I was living in a sober house, and I had relapsed about three weeks prior,” he said. “So, I was kind of hating myself at the time. So I got off work, and I drove out about 40 minutes to South Baltimore and met up with the same guy who had been selling me the same stuff for two weeks.”

Owings got his smack, got back in the truck and started driving. But there was only one thing on his mind. He pulled over about a block away and put the truck into park.

“I did my shot right there in the truck, and I remember feeling all tingly. It was definitely a different feeling that I’d never felt before,” he said. “Normally, I would’ve just sat there for awhile, smoked a cigarette, and then driven home. But on this particular day, I pulled out right after and started driving. I have to think my decision to pull out was my higher power watching over me.”

That’s the last thing Owings remembers. Stopped at a red light in an intersection in South Baltimore in the driver’s seat of a pest control truck, everything went dark.

That was Aug. 28, 2018—the day Owings, 31, overdosed on heroin. The story could’ve ended there. For 115 Americans every day, the story does end there.

But Owings had a different fate.

A nearby motorist saw he was in trouble and flagged down a police officer. Just when the officer made his way over in his squad car, Owings lost control of his body. His foot came off the brake, and slowly, the truck started drifting into the intersection. The officer quickly pulled his car in front of Owings’ truck to physically stop him from drifting any further. The officer got out of his car, hurried over to Owings’ driver side window, and smashed it.

Glass sprayed the truck’s interior—the dash, the floor and Owings’ lap all covered in shards. Owings was unresponsive, but the officer was prepared—he was carrying naloxone, a drug used to revive people overdosing on opioids. Quickly, he administered a dose of it to Owings.

The officer and the concerned bystander who flagged him down stood there in the intersection, waiting for a sign of life. After about two minutes, the naloxone took effect and suddenly, Owings started breathing again.

“I remember there was just a loud ringing, I couldn’t see for like 30 seconds. It took a minute for me to get my vision back,” Owings said. “Then, everything started to come into focus. There was glass everywhere. My vehicle was up against the paddywagon. That was the scariest moment of my life. I didn’t know what happened, who I hurt, or where I was. Thankfully no one was hurt.

“I always believed overdosing was possible. I just never thought it would happen to me. I always thought I was being smart about it,” he said. “But I know that police officer saved my life. Had he not been carrying naloxone, I probably wouldn’t be here right now.”

All hands on deck

Owings is walking proof—naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan—literally brings people back from the dead. By blocking the brain’s opioid receptors, it restores normal breathing in people who have overdosed on heroin, fentanyl, or prescription painkillers such as Percocet. Naloxone can be administered through a nasal mist or an injection. Its effects typically last for 30 to 90 minutes, which usually buys enough time to get medical attention.

A review of emergency medical services data from Massachusetts found that when given naloxone, 93.5 percent of people survived their overdose. The research looked at more than 12,000 dosages administered over two-and-a-half years. A year after their overdose, 84.3 percent of those who had been given naloxone were still alive.

In the thick of an opioid crisis that’s become more deadly than gun violence and car accidents, naloxone is a welcome sight for many policymakers, addiction treatment specialists and, of course, anyone personally impacted by substance abuse disorder.

Earlier this year, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Jerome M. Adams even issued a national advisory, imploring more Americans to carry naloxone and learn to use it. The last time a U.S. Surgeon General issued such an urgent warning was to advise women not to drink alcohol when pregnant.

“It is time to make sure more people have access to this life saving medication,” Adams said in a statement, noting that 77 percent of opioid overdose deaths occur outside of a medical setting and more than half occur at home.

Many paramedics and police officers—including the one who revived Owings—already carry the drug. But the opioid crisis is no longer just for “trained professionals” to address. It’s effectively outsized those confines to the point that it’s no longer just an “addiction” issue—it’s a human wrecking ball.

Now, laws in every state allow the drug to be administered by anyone, from a doctor to a friend who might be actively using right alongside the person overdosing. Although demand is driving up the price, most insurance plans cover naloxone and a majority of states and many cities have issued standing orders allowing anyone to get the drug at a pharmacy without a prescription. Organizations of all types are applying to become Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs to be furnished with naloxone. And groups and individuals that never would’ve previously had to think for a second about intervening in drug abuse, are suddenly getting up close and personal with the overdose antidote.

For instance, every public library in the U.S. will soon get naloxone kits for free. That’s right—librarians are being tapped to form a last line of defense against the country’s largest drug epidemic ever. It’s a strange snapshot of the current state of affairs.

Part of the shift

The Salvation Army, which has long been a leader in addiction recovery with its network of over 140 rehabilitation centers across the country, is adjusting too. Three of its four U.S. territories, spanning 35 states, now have a protocol in place for individual programs to apply for and administer naloxone kits.

Because each state has different policies on how to obtain the drug, it’s up to each program to scope out state and county agencies that might provide both training and the product itself. The protocol isn’t just for addiction recovery programs. Any program—emergency shelter, domestic violence, veteran housing—can apply.

“Opioids are an equal opportunity killer that affect so many different subsets of people. That’s why any program can apply,” said Patrick Riley, Social Service Program Specialist for The Salvation Army, who helped develop the protocol for the Western Territory. Riley’s also a retired paramedic who’s administered naloxone a time or two. He acknowledged that while an anti-human trafficking program, for instance, may be less likely than a rehabilitation center to have to administer naloxone, having a protocol in place is really just a precautionary measure that you hope you never have to use. In other words, just because you don’t anticipate having a fire, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have a fire extinguisher on hand.

Still, it’s a rare plunge into the deep end of harm reduction for an organization that typically takes a more conservative approach with policies such as needle exchanges and “damp shelters.” Despite that, along with criticism that naloxone merely enables drug use by giving users a safety net between them and death, Riley said the organization was virtually in consensus that the timing was right. There’s even research that suggests naloxone has actually been shown to decrease drug use in some circumstances.

“Are we enabling people by giving them naloxone? Yes, we’re enabling them to live,” Riley said.

Closer to the goal

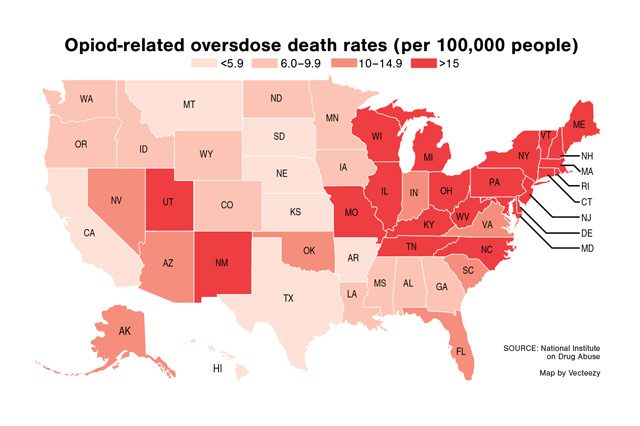

Tim Weber runs a network of sober homes in Maryland—a state with one of the highest opioid-related overdose death rates—and trains other programs on how to administer naloxone. But he was once on the receiving end of a dose—four times, actually.

After a dozen years in and out of jail, shelters, hospitals and a Salvation Army rehabilitation center, he started working in earnest toward recovery. He’s now 15 years in, and thankful every day for the second, third, fourth and fifth chances he got because of naloxone.

“This is a miracle drug. People really are dead when they get a dose of it. It brings them back like Lazarus,” he said. “What’s remarkable is the fact that this drug saves so many people before they die or become brain dead. That’s why access and training are vitally important, because if you can’t keep them alive long enough after the overdose, you can’t get them into treatment.”

Not only can naloxone give people another chance to get help if they so choose, but the near-death experience of a drug overdose and being saved often acts as a catalyst to encourage people to get into treatment with a fresh perspective.

That was very much the case for Owings. After he woke up from his overdose, reality set in like a ton of bricks.

“I was sitting in the back of the ambulance and it really kind of hit me in that moment—I just overdosed,’” he said. “And luckily I was brought back. There are a lot of people that haven’t been blessed with someone being there with Narcan. Who knows if anyone would’ve found me if I hadn’t pulled out and started driving.”

The authorities asked Owings what he wanted to do from there. They could either take him to the emergency room or to a stabilization unit in Baltimore. Owings chose the latter. He spent a night there, then detoxed for a week. That’s when Weber, his sober mentor, helped get him into a 28-day program in Sykesville, Maryland.

“I had always thought I had hit my bottom before that overdose. But I quickly learned—that bottom can always get deeper,” he said. “Recovery is the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in life. But I believe everybody should be given another chance.”

Captain Timothy Rockey, a retired Salvation Army officer, can attest to that. He spent his entire career with the organization working in rehabilitation centers and he keeps a close watch on harm reduction policies. He noted that, contrary to popular belief, it’s usually death that keeps people from seeking treatment.

“From a biblical standpoint, in Luke, it talks about the 10 lepers that Jesus healed. We know at least one of them was a Samaritan because the only one that came back and praised God for being healed was not a Jew, yet Jesus healed them all regardless of what the outcome was. So as an intercession, I think naloxone is a good thing,” he said. “My larger question is, as a society, and as a culture, after the naloxone, then what? Much like our programs in The Salvation Army, we bring them in and we feed them every day, but what are we doing to help them be ‘fishers of men’ and be independent? The danger of naloxone is that, in and of itself, it’s not a holistic intervention. So, I think The Salvation Army is in a good position, because not only can we save them in that moment, but we can save them through a total care approach to recovery.”

And for many, a big part of recovery is simply sharing their story.

Weber recently started an online group called “Naloxone/Narcan Saved My Life” for others like he and Owings to do just that. He wants to connect everyone willing to come forward not only to break the stigma surrounding opioid addiction, but also to piece together a dream he’s had for awhile: a diehard Baltimore Ravens fan, Weber wants to pack as many group members as possible into M&T Bank Stadium on a Sunday.

“I would love to have it announced at a game, ‘Everyone who’s been saved by naloxone, please stand up,’” he said. “I think we might all be amazed.”