by Karen Gleason –

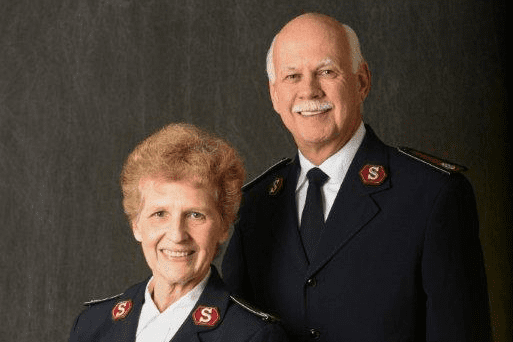

George Scott Railton and family |

One hundred and twenty-five years ago in Philadelphia…

In an abandoned chair factory, a teenaged girl, Eliza Shirley, not only organized The Salvation Army’s first meeting in the United States—she was the preacher! This young blood and fire Salvationist was determined to bring the gospel message to the new world—in an age that did not condone women preachers, to say nothing of her youth. On Oct. 5, 1879, her prayers and efforts bore fruit when her vision became a reality in the United States.

Already a commissioned officer in her native England, Eliza initially did not want to leave her work there. Her father, Amos Shirley, who had already moved to Philadelphia in search of a better life, told Eliza of the ungodliness in America, convincing her that the Army was needed there.

Securing General William Booth’s blessing, after his initial reluctance, and his promise to send reinforcements if her work was successful, Eliza and her mother, Annie, set off to join Amos in Philadelphia—together the family fought to save souls and build a Salvation Army in America.

Within two years, the Shirleys witnessed the conversions of more than 1,000 Philadelphians to Christ and had started two corps. General Booth kept his promise, sending George Scott Railton and seven hallelujah lassies to join the salvation forces in America. They arrived in New York City on March 10, 1880.

In 2005, the Year for Children and Youth, as Salvationists celebrate the contributions and potential of young people, we remember 17-year-old Eliza Shirley, who 125 years ago pioneered the Army in the United States.

At an anniversary celebration this past fall in the Eastern Territory’s Pendel Division, Lt. Colonel William

Carlson stated, “How extraordinary that the movement that today is hailed by management expert Peter Drucker as ‘by far the most effective organization in the U.S.’ was initiated by a 17-year-old girl who bucked the societal culture of her day and even the advice of our founder William Booth.”

When the energy and passion of youth are given over to God, he will work wonders!

Meanwhile, on the West Coast….

The Devil was having his way in San Francisco.

From the Gold Rush of 1849 to the 1870s when the boom was subsiding, San Francisco experienced tremendous growth. By 1870, it was the tenth largest city in the U.S. with 100,000 residents, having grown from a town of 30,000 in tents and shacks in 1856 to a city of brick and stone.

As it still is today, San Francisco was a colorful city. Lawlessness and licentiousness ran rampant, and its famous red light district acquired the name “Barbary Coast”— reminiscent of the coast of North Africa where Arab pirates attacked Mediterranean ships—for its seaport area of brothels, saloons and gambling places.

Pacific Coast Holiness Association

Although sin was commonplace, the Devil was not without foes. In 1882 a group of Christian businessmen from the San Francisco Bay area organized to preach Christ and holiness, calling themselves the Pacific Coast Holiness Association. They set about evangelizing the seamen and others along the waterfront.

When their efforts proved futile, members grew discouraged, and their group of 40 dwindled to 13. It was then that they came across a copy of the London War Cry. Reading about the success of England’s new Salvation Army renewed their incentive, and they decided that San Francisco needed this Army. Therewith they adopted not only the name but as much as possible, the methods and uniform of the Army in England. They even put out four issues of their own War Cry.

Once again, though, after several months their results were disappointing, and they faced ridicule and threats.

Now calling themselves The Salvation Army Holiness Association and led by Rev. George Newton, a Methodist minister, the group wrote to General Booth, asking that he send officers to them so that their struggling movement could become a part of his Army. Unless Booth sent help, it looked like this upstart branch of the Army would die.

While Booth believed that the western U.S. was ripe for evangelization, his problem was that the Army had grown so rapidly in the British Isles that there were barely enough officers to handle the work there. Railton, after expanding the work in the eastern U.S. and in St. Louis, had returned to England to open other fields. He left the Army in New York and Philadelphia in good hands, but there was no one capable of taking it west. Thus The Salvation Army in the West developed independently of the Army in the eastern U.S.

Just when all hope seemed lost and Rev. Newton had decided to seek other endeavors, news arrived that General Booth had agreed to send officers to the West Coast to take charge.

Alfred Wells

The first officer to travel to the West was a young captain named Alfred Wells, 24 years old, a native of Sussex, England, recently returned from service in Ireland. He later wrote his memoirs, which provide vivid details of his experiences as an officer.

Booth summoned Wells, telling him, “You are the man I have been looking for for fourteen months. Are you willing to go as pioneer of the Army in California?” “I’m yours for China or anywhere else,” replied Wells. Booth then gave him a few days to prepare, telling him to report to his office the following week.

When Wells appeared at headquarters, Booth greeted him, “Major Wells!” At first the young captain did not respond, doubting that the Founder could be addressing him when at the time the number of majors could be counted on the fingers of two hands. Booth told him to get his major’s crests for his collar, saying, “You are deserving of all the honors I’m conferring on you.”

The following Sunday morning in April 1882, Wells set sail for America, leaving behind his fiancée, Captain Mary Jane (Polly) Medforth.

Wells arrived some weeks later in New York, and after stops to assist the Army in Toronto, Louisville, Kentucky and Chicago he proceeded to his destination.

“I believe I shed a few tears,” Wells recalled, “before going to sleep in a second rate hotel in San Francisco the first night. I think I prayed the Lord would make a man of me…The fellow who has to make all things new in a new country as a Salvationist has his hands and heart full. Every song was new—nearly all our methods were strange, and to make S.A. of everything was my determination, or at least to use such methods as had proved a success on the other side of the Atlantic.”

God answered this young man’s prayers, and Wells persevered—The Salvation Army had arrived in the West, and was there to stay.

Sources include: Born to Battle: The Salvation Army in America, by Sallie Chesham; The Salvation Army in the West—1883-1950 by Frances Dingman; Reminiscences of Alfred Wells, written in 1925, courtesy of The Salvation Army National Archives; and “When the Stars and Stripes met the yellow, red and blue,” by Paul Marshall.