Program allows inmates to give their child a handwritten note and gift to open Christmas morning.

For families of incarcerated individuals across the U.S., the holidays can be a particularly challenging time.

The Salvation Army’s annual Christmas Toy Lift in Omaha, Neb., helps remind them that they aren’t forgotten.

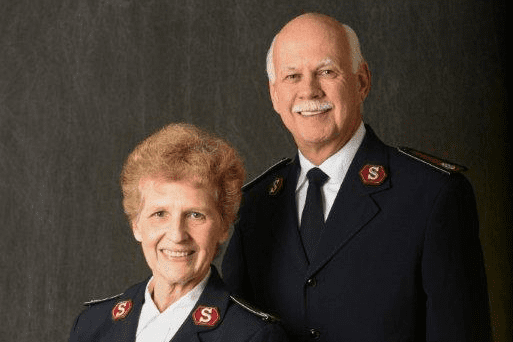

Headed by Don Winkler, assistant divisional social services director in the Western Division, the program allows men and women in correctional facilities to give their child a handwritten note and gift to open Christmas morning, with no indication the gift came from The Salvation Army.

Volunteers from the Western Division have visited jails and offered the Toy Lift program for more than 16 years. The program serves inmates of the Douglas and Sarpy Jails and Youth Center.

“We used to go into the jail with toy catalogs, but in 2007 we started giving $15 gift cards,” Winkler said, “We found we could reach more families that way.”

Preparations begin with Winkler and volunteers visiting jails to perform interviews and paperwork.

For many who participate in the program, it is a chance to reconnect with their child and the child’s caretaker.

“This makes them feel like a person,” Winkler said. “Being in jail, they have no money, no way to get anything to their kids—they feel empowered.”

Kay Weinstein, metro volunteer director for The Salvation Army in Omaha, first got involved with Prison Toy Lift when her son was incarcerated.

“He didn’t have children, but I realized these people needed another shot to be able to have access to their children, to be able to tell their children they care about them, that they are there for them,” she said.

The program that first began serving 600 children has now grown to serve Weinstein’s son and over 1,500 others.

“This is the only thing that a lot of incarcerated people, men and women, can do for their children,” Weinstein said. “Wherever there is a Salvation Army, we’re there to help those children.”

That includes those living outside the U.S.

“If we can get the jail to verify the inmate’s information and children, we will send out a card to them,” Winkler said. “We’ve sent out cards to all parts of the world.”

Weinstein said there is a sense of camaraderie when she and other volunteers visit cell blocks. “You have to realize that some of the people, they don’t really know how to write,” Weinstein said. “They would go to another prisoner and the other prisoner would help them write the letter to their child.”

Many who participate in the program also have language barriers they must overcome. Volunteers and correctional facility employees work together to ensure interpreters are present for those who need assistance.

Both Winkler and Weinstein recall how meaningful their jobs are to them and those they serve.

“There were inmates working in the kitchen, and we were waiting outside the kitchen area,” Weinstein said. “One man came out after working in the kitchen and wanted to send a note and gift to his child but he could not remember the address. It was heartbreaking,”

Many men and women have a hard time keeping track of addresses and contact information over the years, making giving a simple gift a difficult task.

“One of our Salvation Army officers was present at the time and told the man, ‘We will make it happen.’ I felt really good about that,” Weinstein said.

Weinstein stressed the importance of reaching the inmates’ children as those who grow up with parents in prison are more likely to “drop out of school, engage in delinquency, and subsequently be incarcerated themselves,” according to The Sentencing Project.

“People have a very callous idea of prison and it’s not all that great for the children,” Weinstein said. “You want another generation to have good experiences.”