New legislation opens up a debate on restoring services to those “less than honorably” discharged

By Jenny Lower –

As a former machinist in the U.S. Navy, Lloyd Francis has used nearly every benefit he’s entitled to from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical and dental care, vocational training, job placement services—“all of ’em,” the 61-year-old Vietnam veteran said, save for a home loan and military burial.

Yet Francis nearly lost all those entitlements. Currently, he is a resident at The Haven, a Salvation Army center on the West Los Angeles VA Healthcare Center campus that provides housing, counseling, and treatment for up to 2,500 veterans per year.

But back in 1978, he got in a fistfight with a lieutenant who gave him a work order on his day off—a brawl resulting in a court martial that could have landed him in Fort Leavenworth.

Francis got lucky. His lawyer and testimony from his then-pregnant girlfriend managed to exonerate him in court, and suddenly his other-than-honorable (OTH) discharge, was upgraded to honorable to reflect the acquittal.

Without that reprieve, Francis’ life likely would have been much different.

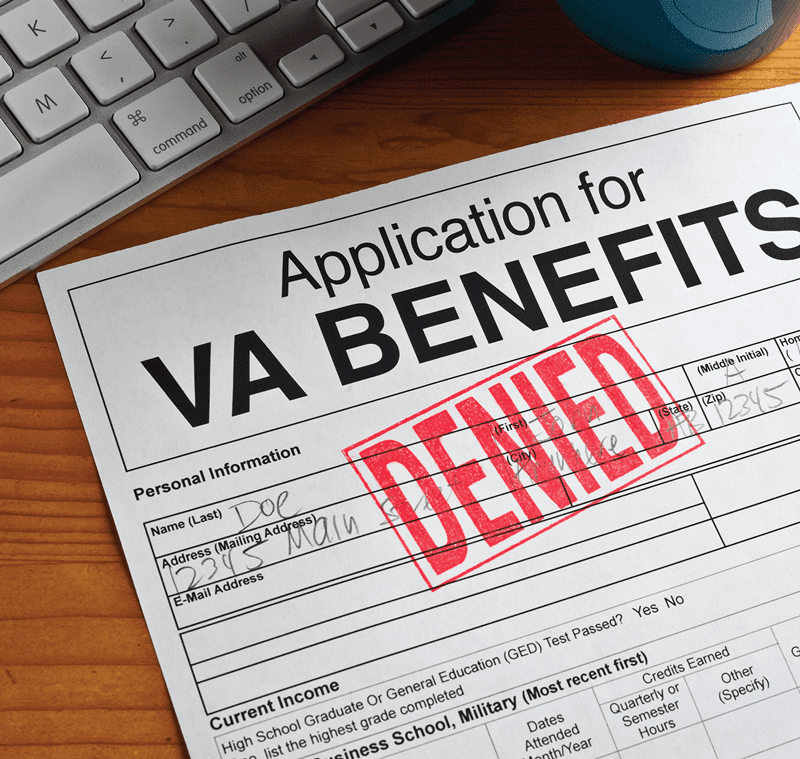

Veterans who receive an OTH or dishonorable discharge from military service—what’s sometimes known as “bad paper”—are barred from receiving regular VA benefits. That, combined with the stigma an OTH discharge often brings when applying for a job, means such veterans face an uphill battle returning to civilian life.

“I feel sorry for them,” Francis said. “It’s messed up.”

Reasons for an OTH discharge can range from failing to report for duty to drug and alcohol abuse, stealing or violent behavior—factors that can stem from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or mental illness. National Public Radio has estimated that at least 100,000 veterans have received OTH discharges in the last 10 years. Many who later attempt to upgrade their status often see their appeals denied.

But recently introduced legislation could one day restore access to VA benefits for these veterans. In March, Rep. Mike Coffman, (R-CA), proposed a law that would shift the burden of proof from those who served onto the federal government. Veterans with a PTSD diagnosis would no longer have to argue that the actions leading to their OTH discharges resulted from trauma. Instead, it would be up to the government to prove they didn’t.

Francis, the Vietnam veteran, said he would support the measure were it to pass, and he thinks most veterans would too. He’d like to see benefits restored to anyone who endured a physical injury.

Since December, Sadaf Joshegha has served as a case manager in the Chronically Mentally Ill division of Victory Place, a wing of The Haven that provides up to two years of housing for veterans with both mental illness and substance abuse problems. Along with case lead Tiesha Davis, she manages a caseload of 10 residents, coordinating their medication, counseling and access to community services.

The facility doesn’t see many OTH residents, but they’ve seen the consequences of the label. As a contracted care provider, The Haven can only service veterans authorized by the VA—generally, those with honorable discharges. Those that do come through their doors are usually exceptions routed there from the VA Hospital or the judicial system.

But a few weeks ago, the VA referred a 35-year-old patient who had served in the Marine Corps Reserve for two years before going AWOL in 2000, resulting in an OTH discharge. Today, he suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and a methamphetamine addiction.

Without antipsychotic medication, he hears “good and bad voices that usually tell him to take off, to leave,” Joshegha said. “If he wasn’t being treated at the time of [military] service, he could have left due to the voices.”

He ended up abandoning The Haven, too. Before he disappeared, Joshegha worked to refer him to a county outpatient clinic in place of a VA treatment center.

“It was so difficult to get him linked” to resources, she said. “County services are so wide and so vague, it’s hard to get them an appointment. That lapse in treatment is what really affects clients who are OTH. They can’t get medication. They can’t get anything treated.”

When the patient ran out of his prescription while still waiting for an appointment, she had to send him to the emergency room. That tactic places a greater burden on taxpayers, Joshegha noted, but few alternatives exist when treatment delays lead to gaps in care. Otherwise, he could have posed a danger to himself or others.

For now, the Haven will work with OTH veterans who want to appeal their discharge status.