We grow and develop almost in tandem with the characters we love.

Every good film in some way wrestles with identity—a character struggling with the gap between who they are and who they want to be. Seeing another person’s journey, no matter how far from our own, often triggers our own reflection. We are highly adaptive creatures, constantly learning from other people’s experiences as well as our own.

It seems like entertainment, but we often carry the lessons learned through film deep in our psyche. We grow and develop identity almost in tandem with the characters we love.

Yet watching a movie and writing a movie are dramatically different experiences. Screenwriters will tell you that what causes growth and development in a character is often not something you would expect.

It’s the people, not the plot, that drives the development of a character’s identity.

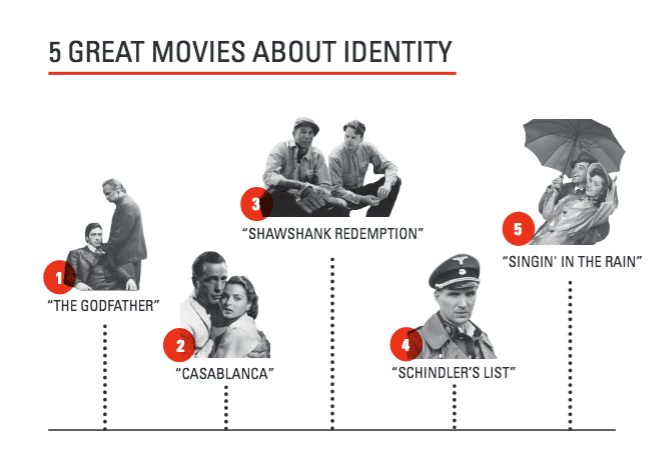

Think of how many great films have centered around the development of identity over time. From “Casablanca” to “Singin’ in the Rain,” and even “The Fast and the Furious,” starring the incomparable Paul Walker, is a story of a young cop trying to decide what kind of person he wants to be. It’s not exactly a high-brow, intellectual journey, but it was a crowd-pleaser. (I won’t disclose how many times I saw it in the theater.)

This development of identity, the “arc” of a character, is what truly powers the emotional payoff at the end of a great film. We want to see our hero begin as someone just like us and transform into someone more powerful, more beautiful, more happy and fulfilled. Sure, the conflict is resolved. The character—with us, the viewers—we may have conquered the world or gotten the girl but we only care because when the movie started we weren’t sure if we could. We weren’t sure who we were. We weren’t sure if we could save the Goondocks or become a Jedi Knight.

And then some immovable force tested our metal and we saw who we were. The plot was set in motion and we overcame!

In so many ways the character arc in cinema is a profound comfort, one that comes from our deep desire to believe that we can change—that we can become who we most deeply desire to be.

In real life change is much more complex. There is no outside author our obvious script. Our script is based on our models, our parents, our teachers, or our culture. Most of us find that making changes to that script can be incredibly difficult.

Rarely do we understand how to build our own character arc. We spend time and energy building sets, designing wardrobe, and perhaps most fruitlessly, focusing on plot.

– Invite friends over to watch your favorite movie centered around the development of identity.

– Give to The Salvation Army’s efforts for arts development in your community at westernusa.

salvationarmy.org

It’s easy to think that if we conquer the dragon or save the princess, the story will be over. The truth is that unless the character has grown, learned, changed—developed—the film is likely to fall flat.

The plot, the sequence of events, doesn’t drive character development. It’s the other way around.

It seems like a simple concept, but a character arc is actually one of the most difficult technical achievements of a film (and a life). And it’s almost solely shaped by a single unusual force: The root desires of the other characters.

A master storyteller will orchestrate the desires of each character in such a way that they can’t ever be in full agreement. They build some characters with a strong desire for justice, some characters with a drive to survive at any cost, some characters with a crippling desire for external approval. The more characters in the story with divergent or opposing desires, the more natural and motivated the plot.

This principle has profound parallels to real life.

Well written characters often have desires that can all be traced back to a singular root desire or “spine” that motivates all of their actions.

Take “Finding Nemo,” for example. Great plot. Lots of twists and turns. But every twist and every turn was motivated directly by the root desire of Marlin, Dory or Nemo.

Marlin is the father of one fish: Nemo. His wife and the rest of their children were tragically lost leaving Marlin with only one desire: protect Nemo.

Nemo is the spawn of Marlin, an overprotective but loving father. His only desire is to grow up and experience life outside his sea anemone.

Dory is a lost blue tang-fish with memory issues and a plucky attitude whose only desire is to help.

In Nemo’s desire to grow up and prove his independence, he swims too close to a boat and is picked up by a scuba diver. Though Marlin has a paralyzing fear of the open ocean, he immediately moves beyond his fear to track the boat that took his son. He bumps into Dory, explains that he’s looking for his son and in her desire to help, the two unlikely friends embark on an adventure.

It’s important to note that Marlin wouldn’t have chosen to be friends with Dory. His desire to protect Nemo forced them together, and her desire to help kept them together. The friendship was forged from each one’s true motivations.

By the end, they’d each grown into who they wanted to be. Marlin learned not to be afraid of the ocean, and to allow Nemo to be independent. He has become, in many ways, the best father he can possibly be. His character has a deep and meaningful arc. His identity has changed.

But imagine that Marlin had found another set of parents that were also afraid for their children and wanted to protect them at all costs. What if he’d been on another reef, not so close to the edge and all the parents had agreed to keep the children confined. If the characters all shared that same spine—the same central point of personality—there would be no plot. No push. No growth. No change. No arc.

Imagine if Luke Skywalker had met Darth Vader before he met Obi-wan Kenobi. His character arc would have been dramatically different. Obi-wan’s core desire helped shape the plot of Luke’s life.

Or imagine if your hovering boss wasn’t pushing you every week, demanding results. Would you be as vigilant about your job if you had to motivate yourself? Is your boss’ desire to control actually driving your character arc?

Are your three closest friends motivated by the same root desire? Or do you have enough diversity in your social circle to make sure that you can grow?

Just like the lead in all great movies, your character and identity are shaped by your deepest desire and the deepest desires of those closest to you. Every day, through your most basic interactions, decisions are made and influence is exchanged. The plot of your life is built by the orchestration of your relationships. But the difference between you and Humphrey Bogart in “Casablanca” is that you’re not just an actor—you’re an author.

You get to determine whether you’re going to star in a comedy or a drama. You get to decide on the trajectory of your own character arc. And while not everything in your life is within your control, your circumstances don’t appear out of nowhere. They are almost always the fruit of your relationships.

You’re allowed to build the relationships you need to be healthy. You’re allowed to seek health for the relationships that aren’t working. You’re allowed to ask for help. You’re allowed to make new friends at any age. You’re allowed to build your own community.

You can choose to orchestrate the characters in your life—your relationships—so that you have a deep and meaningful path to becoming the person you want to be.