With Yuma overwhelmed by migrant families, other communities offer reinforcements.

By Jared McKiernan –

Cesar ran three pizza parlors and made a decent living—before “taxes” anyway. By any standard, he was better off than many of his peers in Guatemala, where over half of the population lives in poverty. But his neighborhood was controlled by gangs, so Cesar had to pay a protection fee to stay safe.

One morning, shortly after he decided to stop paying the fee, he opened his front door and looked down. There on his doorstep, was a bag of body parts with a note attached.

“If you don’t pay, you’re next.”

That was all he needed to see. He packed up, left behind his business and trekked from Guatemala all the way through Mexico, and eventually across the Colorado River into Yuma, Arizona. He was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and later dropped off at a bus stop and transported to The Salvation Army shelter.

Since early April, over 3,800 people—mostly families from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras—have passed through this shelter seeking asylum and, like Cesar, a better, safer life in the U.S.

The Salvation Army opened the shelter late in March at the request of the City of Yuma, which quickly became overwhelmed by the number of migrant families being processed at the border. In the past six months, ICE has released over 168,000 migrants traveling as families in U.S. border communities.

Without a designated shelter to accommodate such a high volume of migrants, The Salvation Army converted its vacant 19,000-square-foot thrift store into one. They staffed it with as many volunteers as they could find, and began providing three meals a day, shower and laundry services, and even basic English lessons.

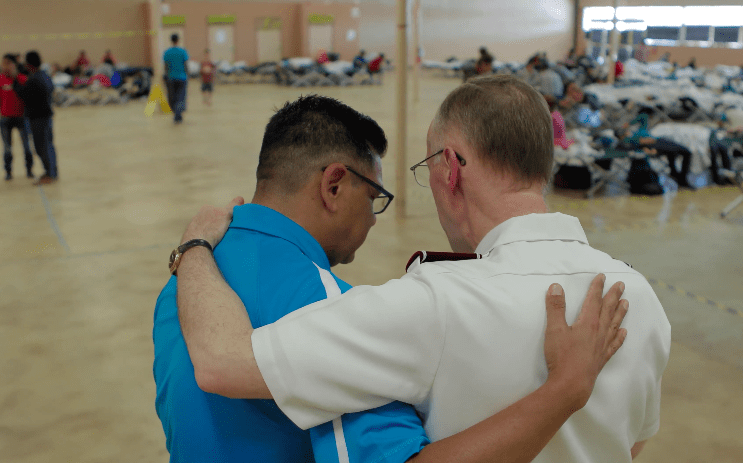

“You never know how local circumstances will offer an opportunity to step forward and be the hands and feet of Jesus,” said Lt. Colonel Kelly Pontsler, Southwest Divisional Commander for The Salvation Army. “We’ve adopted the simple motto from 1 Corinthians 13: Love is kind. Simple acts of kindness can be life changing, so we’ll just keep showing up with kindness.”

While some asylum seekers are routed onto buses or planes relatively quickly to go to other parts of the country for sponsors and court hearings, most have to stay three to five days until their travel arrangements are set, according to Captain Jeffrey Breazeale, Yuma Corps Officer. That doesn’t mean they have valid asylum claims, but it’s a risk they’re willing to take.

“I’m seeing the need is real for some; for others, it’s a means to an end,” he said. “I’ve heard just about every story from the families coming in—fleeing persecution, fleeing unfit living conditions, looking for work, wanting to be closer to family in the U.S.”

Yet, while the need is imminent, a reprieve is not. The organization has been maxed out with volunteers and resources for more than two months now, and like many nonprofits working at or near capacity, the pace is simply unsustainable.

“Our volunteers are tired, our employees are tired and it’s not stopping,” he said. “What the city told us is, ‘this is our new norm.’ We will not be able to sustain our services on the local budget. So we’re now tapping Emergency Disaster Services (EDS) funds.”

Yuma is home to The Salvation Army’s biggest shelter for asylum seekers in the Western Territory, but it’s not the only city in which it has a presence, according to John Berglund, Territorial EDS Director.

Five-hundred miles east of Yuma, The Salvation Army is putting in work in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Since federal authorities began dropping off migrants on April 12, The Salvation Army has been serving three meals a day, six days a week. They also just set up a shelter in Tucson, Arizona, and three corps in Phoenix have started producing meals for a network of Hispanic churches, which have been serving this population for several years. And in California, they’re looking at setting up a shelter in Palm Springs to help with the overflow.

“It’s an emergency for us because it’s people in need,” Berglund said. “Whether it’s a declared emergency or not, we will still respond to people in need.”

Captain Noel Evans, Las Cruces Corps Officer, noted that because The Salvation Army is the only organization feeding this population in the city, it’s imperative that they do so, but it’s also a privilege.

“We’re up to 350 meals three times a day now, which is the most we’ve ever done,” she said. “They’re home-cooked meals. Tonight we’re making chicken alfredo. We make everything with love and show them the love of Christ.”

Beyond meeting the families’ basic needs, she’s been listening to a lot of their stories.

“I’ve cried a lot with the families. The fact that they made it, and that they had to probably go through things that are unthinkable, unspeakable to us, but they get a second chance at life—I just hug them and I cry with them,” Evans said. “They left everything they loved behind. I think we forget that these are people and they hurt and they suffer. They’re wives without their husbands. They’re children without their mothers. And they’ve come here for a chance at a better life.”

She remembers one boy from Honduras who was 16 years old and seeking asylum with his father, so he could work in the U.S. and send money to his mother and younger siblings back home.

“This young boy has never had a childhood,” Evans said. “From the moment he can remember, he’s always worked in plantations. He’s always worked—period. He’s never gone to school or done anything. And now, he’s come to the U.S. and he’s still not going to have a childhood. He’s still not going to go to school because he’s going to work and work and work to send money back home to his family.

“It just puts it into perspective. He’s come over here for a better life so if I can sit there and make him a home-cooked meal to stick to his bones, that he will remember me by, then I will do it,” she said. “Through the love of Jesus Christ, I will do it.”

Cesar’s name was changed for this article