by Rick Hampson

In Morgantown, W. Va., when the red kettles appear each year, the questions start: “When’ll he drop it? Has he dropped it? Will he drop it?” Finally, the Salvation Army commander’s phone rings. The bank has a simple message: “It’s there.”

For 25 years, through war and peace, boom and bust, someone has secretly dropped $1,000 into a kettle at Christ-mastime in this otherwise unremarkable college town.The mysterious gift has evolved into a seasonal meditation on the meaning of giving.

In 1972, inflation was rising so fast President Nixon had imposed wage and price controls; Vietnam peace talks were so slow he’d resumed bombing North Vietnam. In a period of three days, four B-52s were shot down. Someone had broken into Santa’s House on Courthouse Square twice in a week, stealing lights and decorations.

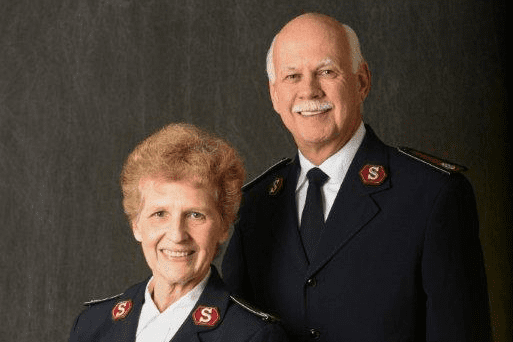

The community’s new Salvation Army commander, Capt. William Crabson, was trying to brighten this grim season, but he’d had trouble getting articles in the newspaper. He went to see the editor.

Then, on December 12, Crabson got a call from the First National Bank president. “I have a friend who wants to make a large donation, but he doesn’t want anyone to know,” the banker said. “It’ll be in the kettle in front of the bank, wrapped in a $1 bill.”

The Captain didn’t have to feign surprise for the kettle volunteer’s benefit when he unfolded the dollar bill: he was looking at the face of Grover Cleveland. The story not only made the local paper, but also papers around the country.

In 1972, a thousand dollars was still a lot of money, especially in one of the country’s poorest states. Morgantown had something to talk about besides the economy. The day after the story broke, contributions doubled. By Christmas the kettle drive had raised $7,400, a quarter of the post’s annual budget.

In the years that followed, the same scenario was played out, and the spirit seemed to be catching. In 1973, a poor little boy brought eight cents to the town’s Christmas party so Santa could have a Christmas present. In 1981, another anonymous donor put in $1,000, in hundreds. The following year, someone dropped five one-ounce gold coins into a kettle in Crystal Lake, Ill., spurring a Christ-mas tradition that spread through the Chicago area.

Meanwhile, the $1,000 Christmas donation became Morgantown’s version of Punxsutawney’s Groundhog Day.

Everyone wondered: Who was the donor? A few found out. One year, Crabson got the call and arrived at the kettle a little early. He saw a man, accompanied by the bank president, dropping something into the pot. It was Hale Poston, an elderly, old fashioned lawyer who didn’t even drive. Poston died in 1983, but that Christ-mas, nothing changed: same call, same kettle, same amount. His role had been quietly assumed by the bank president, Martin Piribek. When Piribek died in 1992, however, those who suspected he was the donor wondered what would happen.

For one thing, the $1,000 bill disappeared. Instead, for the next three years, The Salvation Army received two 1934 $500 bills. In 1995, the donation came in the form of an 1881 U.S. $10 gold coin worth about $1,000.

Now, the donations were turning up in different kettles at different times before Christ-mas. Sometimes December 25 drew ominously close, making people worry.

The tradition continued, and so did the spirit it symbolized. Last year, the Morgantown Christmas kettles collected $100,000–up $92,600 from 1972–and The Salvation Army served more people in a month than it did in all of ’72.

“The money’s nice,” says Lt. Roy Williams, corps officer in Morgantown since 1994, “but the story is worth a lot more than a thousand dollars.”

The story leads some Morgantowners to think about the meaning of giving, and to regard the town’s Christmas tradition as a mystery in a deeper sense.

Then one time a man met with Williams and explained what happened.

“I was outside the bank about ten years ago when I saw this guy put the thousand dollar bill in the kettle,” he recalled. “I asked someone who it was and he said Piribek the banker. So when Martin died, I thought someone should keep it up. It’s a neat tradition,” he says. “My family and I do it and then we sit around and giggle. People ask us, ‘Who do you think it is?’ and we suggest all kinds of candidates. It’s almost indecent to get so much enjoyment out of this.”