Tucked into the village of Tilonia in Rajasthan, India, is a school that is redefining what it means to receive an education and breaking down barriers for rural villagers across the developing world.

As a young college student in the 1960s, Bunker Roy volunteered to serve in relief efforts following a severe famine in a poor area of India. He was on the path to success as a student at St. Stephen’s College in Delhi, but experiencing the reality of life for rural villagers changed his plans for the future.

“I left college in 1967 and on the first of November, I decided to leave the world I knew to live and work in the villages of Rajasthan,” Roy said. He traded in a three-piece suit for the kurta pyjamas worn by the locals in Rajasthan, one of the poorest states in India. At conferences and at home, he still wears the kurta wherever he goes. Roy signed up to work as an unskilled laborer, deepening wells by lowering down into them on a rope and tossing explosives into the darkness below.

“I lived with very poor and ordinary people under the stars and heard the simple stories they had to tell of their skills and knowledge and wisdom that books and lectures and university education can never, never teach you,” Roy said. “My real education started then when I saw amazing people—water diviners, traditional bonesetters, midwives—at work.”

After five years of manual labor, Roy decided to put his education and resources to use by opening a community college in Tilonia with the help of other young graduates.

“I had no projects, no programs and no money to offer,” Roy said. “Only my enthusiasm and my two hands.”

Barefoot College opened in 1972 in an old, government-owned tuberculosis sanatorium that Roy rented for $1 per month. The school combined urban education with local traditions and values.

“The demystified, decentralized, community managed, community-controlled and community-owned approach put the traditional knowledge and village skills of the rural poor first,” Roy said. Today, former students run Barefoot College rather than college graduates from the cities. “It is, I believe, the one and only college in the world built by the poor, managed by the poor and owned by the poor.”

It grew into much more than a school.

“Barefoot College is the most extraordinary environment,” said Meagan Fallone, head of global strategy and development at Barefoot College. “It’s a place where every day 300 people wake up and say ‘why not’ instead of asking themselves ‘why.’”

From the beginning, Barefoot College developed based on needs identified by local villagers. “Every day has been a concerted effort to respond to a real need from a real person in a real community,” Fallone said.

Barefoot College has no religious affiliation but is deeply rooted in the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, with particular emphasis on Gandhi’s belief in the importance of community traditions, values and self-sufficiency.

“We try to act as a catalyst and a support system to communities by really using the skills that rural communities have within them to try to draw them out so that they begin to have confidence in their own abilities and to augment their quality of life by giving people confidence and competence and the sense that they have the potential to make their own way to something better,” Fallone said.

Barefoot College is first a center of education, providing balwadis (rural crèches), night schools, bridge courses and day schools for children and teenagers. The night school program began shortly after the college was established and has become one of it’s most successful educational programs, a way to bring relevant education to rural kids who didn’t have access to school.

In rural India, 60 to 70 percent of children are unable to attend school. Most of the students are girls who are often discouraged from pursuing an education outside of the home. At Barefoot College, boys and girls learn side by side. The teachers are community members, most of whom are graduates from the program themselves.

“The thing that is so unique and innovative about the Night Schools is that the curriculum is very place-based,” Fallone said.

For example, a “Children’s Parliament” teaches children how to function within a democracy and gives them a sense of importance. The parliament, started in 1993, works with village committees to govern all of the night schools across India and in other parts of the world. Members campaign and are elected by their fellow students.

“The civil society component is how we teach kids to make democratic decisions, how to put your hand in the air and have an argument that is intelligent,” Fallone said. “These are all very important skills in having democratic societies.”

The program takes five years to complete and is not age-specific. Curriculum is hands on and encourages students to learn by doing.

“I think there’s a huge trend right now in the redefinition of education and that relevant education is really important now,” Fallone said. “Not everybody needs the same education.”

After completing their night school training, students have the option of transitioning into traditional schools with the help of Barefoot College officials.

“The students who do this finish in the top 12 percent so; even if it’s a little harder for them, they have the skillset to be able to take on quite tough work,” Fallone said

Since opening in 1975, the night schools have taught 75,000 students, 14,000 of whom now work in government-run schools.

But the success doesn’t stop there. In 2008, Barefoot College began what has become its most famous program: a solar engineering training program for grandmothers from villages throughout the developing world.

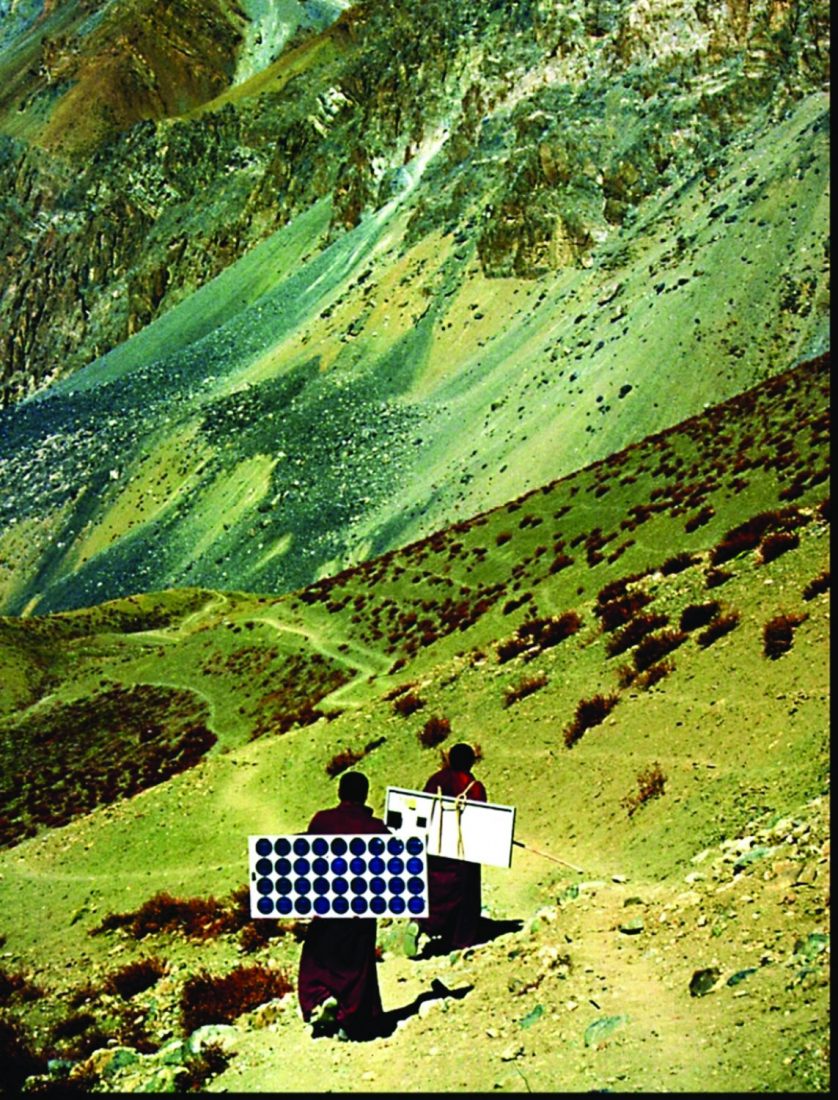

In rural villages, grandmothers are generally women over the age of 35. They are flown to the Barefoot College campus in Tilonia where they spend six months learning to build and repair solar panels. Most of these women have never left their villages. They don’t speak the same language as each other or as their instructors and are unable to read or write. They learn through demonstrations, sign language and determination.

“This is not only about training a woman as a solar engineer but demonstrating that even the very poor have the capacity and competence to learn the most sophisticated skills and they can also serve their communities,” Roy said.

Once women are trained, they return to their villages where they build, install and are paid by a village energy committee to maintain the solar panels that light their village, sometimes for the first time.

“The best woman solar engineer the Barefoot College has trained is a 55-year-old grandmother from Faryab in Afghanistan who is looking after 200 houses she solar electrified in September 2005 and they are still functioning without any problem,” Roy said.

Women are selected for the program based on observations by Barefoot College staff who look for curious, natural leaders who have the support of the village.

“These women are absolutely rooted in their communities,” Fallone said. “If you capacity build them, that competence is not going to leave their community.”

A key element of the program is that women are trained to train other women––the trainee becomes the trainer. Through these methods, Barefoot College has trained more than 600 women from 1,000 villages in 64 countries to build, install and repair solar panels.

“We’ve really answered a very strong response to a shift in the development world,” Fallone said. “People were really dissatisfied with the top-down approach so there really has been a cry for models that are bottom-up, grassroots, community-based and this one addresses so many issues.”

For Roy, every day at the Barefoot College is an opportunity to prove that the impossible is possible.

“Tilonia gives me a challenge every day,” Roy said. “It is not one lifetime’s work but many in one. The thought that I have managed to help so many people has kept me going.”