Under new law, drug addicted pregnant women can be charged with assault.

By Erin Wikle –

Tennessee State Governor Bill Haslam signed into effect State Bill 1391 on April 29, affecting women who use narcotic drugs while pregnant and likely impacting organizations, including The Salvation Army, that serve people struggling with addictions.

The law, effective July 1, states that a woman can be prosecuted for assault if she takes a narcotic drug while pregnant and the baby is born addicted, is harmed, or dies as a result. The woman can, however, avoid criminal charges if she completes one of the state’s approved treatment programs.

The Tennessee State Department of Health recorded 921 cases of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS), or “drug withdrawal” in infants in 2013. This reflects a near 10-fold rise in the incidence of babies born with NAS since 1999.

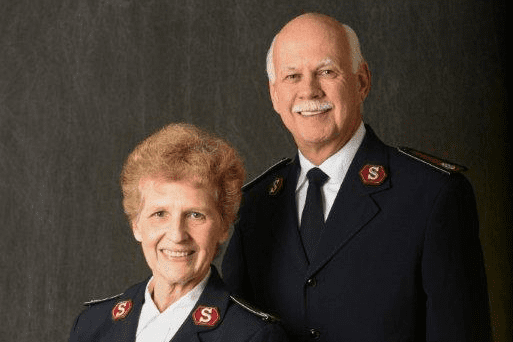

Memphis is home to Tennessee’s only Salvation Army Adult Rehabilitation Center (ARC) since the Nashville facility closed after the record-breaking flood of 2010. Currently the Memphis ARC offers recovery programs for men only, but it is expanding to include women this autumn. In addition, with a new Intensive Outpatient Program slated to open in June. the Army will be able to serve more than 100 women and children each day.

“We believe that we are particularly and increasingly well positioned to serve addicted women along with their children here in Memphis,” said Captain Jonathan Rich, Memphis area commander. “With the current changes in Tennessee we will have expanded our capacity to be the leading provider of rehabilitation services for women, and their children, in the western part of the state.”

The Salvation Army’s Renewal Place in Memphis is a transitional housing program for chemically addicted women and their children. The program is unique in that it allows mother and child to stay together during the recovery process, which can be up to two years. With intensive case management and training partnerships for both mothers and children the program helps to stabilize two generations of both addicted and drug exposed individuals.

While some see this new legislation as a step in the right direction for addressing the issue of wide-spread and illicit drug use in Tennessee, others pose concern as to whether the law will only cause more questions and criticism to arise while creating further financial strain on the state and its subsidiaries. “Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness,” published by the Journal of American Medical Association, reports that drug dependence costs the U.S. approximately $67 billion annually in crime, lost work productivity, foster care, and other social problems.

Sergeant Ernie Simms, corps officer at the Berry Street Corps in a run-down neighborhood in East Nashville, posed questions that remain, for the time being, unanswered: What will happen to the existing children of single, drug-addicted mothers who are given the option of either rehab or jail? Is the foster care system prepared for the influx of children who could potentially wind up in custody of the state? What is the response to the generational problem arising when a child is taken from his mother—even his opiate-addicted mother—and no bonding takes place? And even if mother and child are reunited, who has taught this new mother how to raise her child and parent effectively? Is the state prepared for the influx of women who will be incarcerated for illegal activity and will require prenatal care until her child is delivered?

No doubt The Salvation Army will continue to offer relevant programming, recovery, and holistic rehabilitative services to those in greatest need. With the restoration of the drug-addicted individual its priority, The Salvation Army must consider all implications of drug use both short and long term, including health, housing, employment and the ability to cope with day-to-day scenarios.

It is critical that those in the field serving as corps officers and lay leaders be prepared to help throughout the entire recovery and assimilation process. As a movement so involved and entrenched in its communities locally and internationally, the Army’s response must be that of urgency—to comfort the broken mother, to help the suffering child, to bring hope to hurting families.