The Salvation Army partners with an elementary school on Montana’s Crow Indian Reservation

By Jared McKiernan –

For residents of Sheridan, Wyoming, a simple shopping outing usually means crossing state lines. The nearest major retail hub is all the way up in Billings, Montana, a little more than two hours north on the Interstate 90. It’s quintessential rural, small town America, so there’s not much along the way to pique the interest of patrons-to-be.

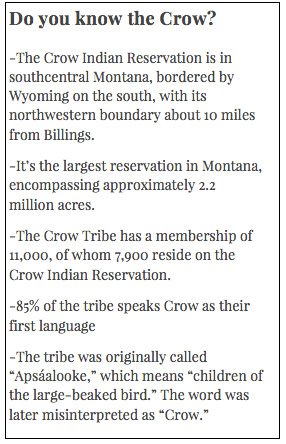

But for the past year, whenever Captains Matthew and Charleen Morrow would make the trek from Sheridan to Billings, they’d pass a town called Lodge Grass, and perk up. Situated on the historic Crow Indian Reservation, the 450-person community is not hard to overlook, spanning just 0.3 square miles. Its high school, junior high and elementary school all share a building. And like many areas in and around American Indian reservations, it’s plagued by high poverty and unemployment, and a litany of other social issues. So, while many motorists would cruise past the reservation without a second thought, the Captains would consider the possibilities.

“We were driving past the Indian reservation for a year, and just thinking ‘I wonder what’s going on there,’” said Charleen Morrow, who was appointed with her husband to lead The Salvation Army Corps in Sheridan in 2016. “We had this great opportunity, culturally, sitting right next to us.”

“We were driving past the Indian reservation for a year, and just thinking ‘I wonder what’s going on there,’” said Charleen Morrow, who was appointed with her husband to lead The Salvation Army Corps in Sheridan in 2016. “We had this great opportunity, culturally, sitting right next to us.”

The director of a nearby food bank mentioned to the Morrows that he and his wife go up to the Crow Reservation once a year and hand out coats. “We just told them, ‘We get a lot of coats donated. If you ever need anything, let us know,’” Morrow said. “Within literally a week of that conversation, we got a letter from Lodge Grass School District asking us to come and have a meeting with them.”

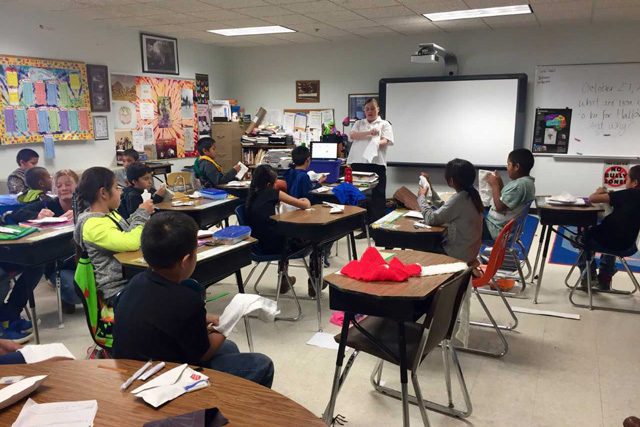

At the time, the K–6 elementary school there was only aware of The Salvation Army’s thrift store and food bank, so the Captains briefed them on all that they do—particularly their character-building program for kids.

The Morrows’ own backgrounds were also of interest. Matthew Morrow holds a degree in Montana Native American history, and Charleen Morrow previously worked for the State of Washington as a foster parent recruiter and retainment coordinator. So part of her job was to teach classes to prospective foster parents on how to meet the unique needs of children in foster care. A lot of those needs, she found, mirrored those of reservation kids.

“Some of the things I’d teach the parents were things that the students weren’t taught at home, before they became a foster child,” she said. “A lot of times foster children don’t know the basic things, like ‘why do you wash your hands every day?’ So I drew a little from those classes and combined it with some of [The Salvation Army’s] troops materials, which we use for a lot of youth programs.”

After the meeting, the Captains dropped by the school as guest speakers to give the kids a lesson in basic hygiene. The Morrows hope it’s the first of many opportunities to engage the students on the reservation. Next time, they’ll be talking about the importance of responsibility to oneself and others.

After the meeting, the Captains dropped by the school as guest speakers to give the kids a lesson in basic hygiene. The Morrows hope it’s the first of many opportunities to engage the students on the reservation. Next time, they’ll be talking about the importance of responsibility to oneself and others.

“We’re highly affected by unemployment, so there’s only a couple little businesses here and the school,” said Melanie Ferguson, Lodge Grass Elementary School Principal. “A lot of our students are being cared for by other family members. And we’re trying to fill in the gaps for their care and nurturing, their social engagement, their academic and behavioral excellence, as well as their nutritional needs and their health needs. So we’re just trying to help them in any way we can.”

Lodge Grass was one of just six recipients in the nation of a recent $60,000 grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, designed to improve the well-being of children in low-income communities. Though some 68 percent of Lodge Grass residents fall below the poverty line, at least part of the town’s woes can be attributed to a lack of activities to keep children engaged. That’s what Ferguson likes so much about the Salvation Army partnership.

“My hope is that students’ needs are met in a way that makes them feel warm, comfortable and safe in school,” she said. “We want them to feel cared about and therefore be more engaged in learning activities, and maybe their attendance will improve.”

Historically, school attendance hasn’t exactly been a crowning achievement among reservation communities, and Lodge Grass is no exception. Compared to their white peers American Indian students are over 65 percent more likely to lose at least three weeks of school per school year.

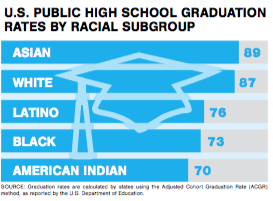

Unsurprisingly, researchers have linked chronic absenteeism (even in a single year) with an increased likelihood of dropping out. And although the public high school graduation rate in the U.S. recently hit a record-high 82 percent, American Indian students continue to lag behind. Just 70 percent of the class of 2014’s American Indian population graduated on time—trailing every other racial subgroup.

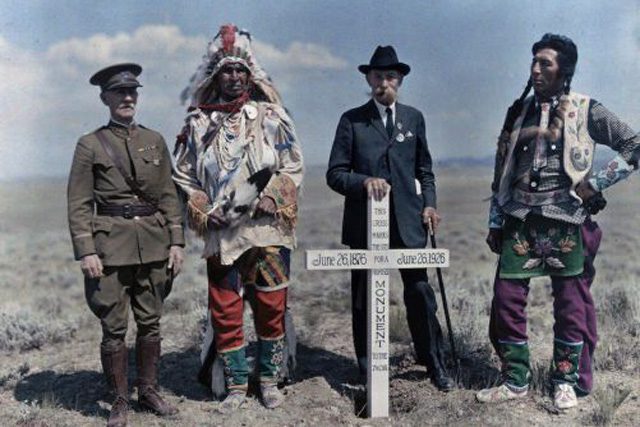

“If you think of the things that typically cause absences, and you think about a Native American kid, there’s a lot of history of Native American young people being separated from their home communities, their home languages, and placed into boarding schools,” said Hedy Chang, Executive Director of Attendance Works, a national and state initiative that promotes awareness of the important role of school attendance. “This didn’t happen that long ago. We’re talking 1960s—a lot of these kids’ parents experienced that. So their sense of school as an engaging welcoming place committed to their future is not exactly there.”

Lawmakers in Oregon recently launched the Tribal Attendance Pilot Project (TAPP)—a $1.5 million effort to reduce chronic absenteeism among native students in nine Oregon districts. The project’s family advocates work to build a culture of attendance and help American Indian families learn to build trust with public schools. Local store employees even call if they see students skipping school. TAPP, which has yielded some encouraging results, suggests that regular attendance and student engagement has to be a community-wide effort.

For Lodge Grass, that community happens to be in two different states. And that’s perfectly OK.

“We want to make sure that their community knows that we support them,” Morrow said. “We’ve had a lot of interaction with them through the years through our food bank, but as far as us going out of our walls, this is the first time that this has happened.”

The Morrows said they’ve been praying about the possibility of bringing Lodge Grass students out to Sheridan for Sunday worship. They’re also planning a Pow Wow with the school—just another way to engage with the student population and celebrate their culture.

“We’re just excited about being there,” she said, “and excited about the opportunities that can be.”

This is the third in a series of articles by New Frontier Chronicle showcasing different expressions of ministry across The Salvation Army USA Western Territory that point up the importance of reaching out to other ethnic and linguistic groups so as to build a more vibrant and inclusive Church. View the rest of the series here.