We see stats about addiction. We see substance abuse portrayed in film and in TV shows. We might even know someone who’s personally faced addiction to drugs or alcohol. But most of us don’t really understand what causes addiction, and why our brains respond the way they do to drugs.

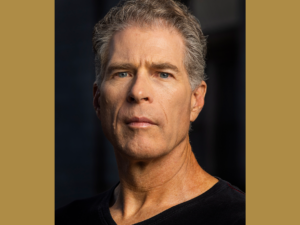

Dr. Judy Grisel has made it her life’s work to unravel the mysteries of addiction, striving to uncover its root causes.

A distinguished behavioral neuroscientist whose expertise spans the fields of pharmacology and genetics, Dr. Grisel’s groundbreaking research draws from her insights into addiction. These insights aren’t just academic though; they’re also deeply personal.

Dr. Grisel’s journey has been shaped by her own experience with addiction, which has given her a unique vantage point on the subject.

Her passion for understanding the neuroscience behind addiction led her to deliver a powerful TED Talk titled “Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction,” which captivated audiences around the world. She wrote a book of the same name.

With a career dedicated to advancing our understanding of addiction, Dr. Grisel is on the show to share her knowledge, insights and research findings, shedding light on this complex and often stigmatized topic.

Show highlights include:

- Dr. Judy Grisel’s background and what sparked her interest in behavioral neuroscience and addiction.

- How her own experience influenced her approach to studying addiction.

- Key factors that contribute to addiction, according to her research.

- How genetics and pharmacology play into her research and what genetic factors can influence susceptibility to addiction.

- How the brain’s reward system drives addictive behaviors.

- How a better understanding of the neuroscience of addiction can lead to more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

- Why it’s more impactful to incentivize recovery instead of punishing addiction.

- What Dr. Grisel sees as the biggest misconceptions surrounding addiction.

- Advice and resources for families or individuals dealing with addiction.

- How you can better understand and help those facing addiction.

- What you can do to help and understand those facing addiction.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: Dr. Grisel, welcome to The Do Gooders Podcast. Thank you so much for your time and for joining us today.

Dr. Judy Grisel: Thank you. I’m happy to be here.

Christin Thieme: Can you start by telling us a little bit about your own story and maybe what sparked your interest in this field of behavioral neuroscience and addiction?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Sure. I’d be glad to. I grew up in New Jersey and I was kind of a typical Jersey girl, normal more or less life, and everything looked probably just fine until I tried my first drink, which was at 13, and I drank quite a lot and I loved it. It really changed the trajectory of my life. I went from that drink to getting my hands on as many mind-altering chemicals as I could whenever I could, however I could, and just completely came off the rails. I was kicked out of three schools by the time I was in my 20’s and I was homeless. I had contracted Hepatitis C from sharing needles. It was right around the time of the AIDS epidemic getting started. So I’m lucky I didn’t catch HIV, but I basically ended up driving myself into the ground, pretty miserable, yet I couldn’t see that drugs were my problem and I fortuitously ended up in treatment.

And that’s kind of a long separate story, but it wasn’t my intention. It wasn’t like I realized what I was doing. I just crashed and burned, got to treatment where I learned that addictions were mental illnesses and that if I wanted to live, then I needed to be abstinent. That’s what they said. And I thought, “No way.” I don’t want to live that much, and I definitely don’t want to live abstinent, because it seemed like that would be more or less the end of the fun for me, even though it wasn’t that much fun at that point. But still, I wasn’t convinced. So I figured kind of naively and arrogantly that if I had a disease that was killing me, all I needed to do was cure the disease and then I would be able to use.

So even though I had on paper not much potential, I was determined like most of us are and I finished college. It took seven years. I got my PhD in neuroscience, got another seven, did a postdoc. And my goal really was to try to fix what was wrong with my brain so that I could not self-destruct. And I was at the same time taking advice about staying sober and working on that. And so I kind of got tricked into it, I guess. I got tricked into recovery. And surprise, surprise, my life was a zillion times better. So it wasn’t always wonderful, but it was definitely more interesting and more enlivening and I had better relationships and my skin looked better. I look at myself in the morning without disdain. So yeah, things got much better. So that’s how I got into it.

Christin Thieme: So no surprise there that your personal journey really had a significant role in your work. That’s kind of an amazing story and probably gave you a whole new perspective than a lot of the people that you were studying alongside. So how do you think those experiences influenced your approach to studying addiction?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Yeah, it’s a good question. I think for when I was younger, I felt like that my addiction was kind of a big flaw that I needed to cover up and that my past was not something to acknowledge if possible, and definitely not to celebrate. I’m really grateful to be alive, so don’t get me wrong, but I do see now what you’re alluding to is true, that kind of my worst experiences and my hardest times really help inform what I do, what I love about my life today, and more importantly, I think how I can be useful to other people.

So I didn’t see that. And along those lines, what made me a sort of terrible addict was that I had a strong self will. I was really persistent. I took risks. I was single-minded, and I was determined to always be pulling the levers to get what I wanted, a different feeling, a better feeling, more of that feeling, this feeling and that feeling. And those exact same traits are what make me a good scientist I think. I’m really curious. I’m really determined. I have kind of a tough skin. There’s a lot of rejection in everything, and it doesn’t seem to affect me like it does some more delicate types. I can really single-mindedly pursue my goals, and I think it’s helped a lot.

And then like you say, I have a kind of unique perspective. I don’t think I’m the only one. I think there’s other people like me, but I can see it from both sides. So I can see where the scientists get really lost sometimes in the trees and they don’t even see the forest. It’s the most obvious thing. Some studies are missing the boat I think, and I can see where people who are suffering with addiction don’t understand the basic neurobiology that makes our behavior reflect a disease state where we lose our choices, we lose our options, and we’re kind of desperate.

Christin Thieme: In your research, you delve into the root causes of drug addiction. So what would you say are some of those key factors that you’ve discovered that would contribute to addiction, especially from your studies from a neuroscientific perspective?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Sure. And all of my understanding is based on my little research in the lab, but more importantly, it’s based mostly on what this large body of science and biomedical research is showing. So I read the literature and I try to understand it, and there are three main causes of addiction. The reason I’m like the way I am, I think comes from three sources. The first is what I inherit, and that turns out to be much more complicated than we thought, but about half of an individual’s risk for developing substance use disorder comes through our DNA. So we’re kind of born with it. Some people are liable and some people are kind of protected naturally. And then the other half obviously is environmental. And that’s all kinds of things, including what your family life is like. And if you have trauma or stress or you have good access to drugs.

In many cases like mine, it’s just like a random occurrence. One day in middle school I decided, “Oh, let’s drink this.” And I was off to the races. But probably the most potent influence is exposure to addictive drugs during development, which everybody realizes, I guess, is when most people first try addictive drugs. So kids are prone to risk taking and to novelty seeking. And of course, drugs are known to be risky and new, and so they’re likely to pick something up. And when they do, because their brain is so malleable during development before you’re about age 25 or so, it kind of primes the brain to develop an addiction. And addiction in a way is kind of a memory that drugs are coming, and so it makes you adapt. And so I think that in my case, I had a little bit of a genetic predisposition, a little bit of environmental stuff. My mom was probably depressed and I was bored out of my mind and this and that, but maybe not so unusual, but I think the big catalyst was this half a gallon of wine I drank when I was 13.

Christin Thieme: You talk about genetics. Can you explain a little bit more for people who don’t have the same background as you do, what are some of those genetic factors that can make you more susceptible to addiction?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Well, it’s a great question. So we thought 20 years ago or 25 years ago that there were going to be a few genes that were kind of like smoking guns. If you had this gene, then you had the gene for addiction. That is not at all the case. The genetic code and genetic influence, which we get from both our parents, our biological parents, and also their experiences through epigenetics and our grandparents’ experiences. So that’s a new kind of layer onto this. But anyway, what we inherit in our DNA is lots of genes that influence your propensity for addiction, but only each contribute a very small amount. And many of those might make you more at risk and others might make you less at risk. So it’s kind of a complicated mess, but I can give one example that happens to be one that’s kind of close to my heart because my laboratory research is based on this.

It turns out that, and I would bet about me, this is true. If you look at people with no alcoholics in their family for about two generations, and you compare them to people who have at least two alcoholics in their parents and grandparents, they have different levels of opioid peptide called beta endorphin. And endorphin stands for endogenous morphine. So it literally is like morphine that we produce ourselves. It’s a neurotransmitter like morphine. And so what I just said is that people with the family risk have low endorphin, really about half as much, and so they’re kind of deficient in endorphin just by virtue of who the alcoholics may be in their family. So this is a heritable trait. So people are born with naturally low or naturally higher levels. And when people with a positive family history with a deficiency drink alcohol, it really does the trick and it raises endorphin levels tremendously. So they’re very sensitive to alcohol’s effect to be able to release endorphin.

So of course, like for me, probably it felt so great because it really was, it was medicating this deficiency and then some. I suddenly felt like I’m at peace with the world, things are cool, I’m relaxed, I fit in, I’m not insecure, and I thought I had the ticket. Now again, people with negative family history, they might get a little buzzed, but not the same. So really at the first time somebody is exposed to all drugs, but I’m just giving this example with alcohol, their responses vary, and part of that variation is due to what we inherit.

Christin Thieme: It’s so fascinating. You’ve talked a lot about the concept of never enough and it being so powerful when it comes to addiction. How does the brain’s reward system in neurochemistry contribute to this feeling and how does that drive our addictive behaviors?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Another good question. Well, our brain does not like to be high. It’s unfortunate. It really is. It likes to be stable, and in fact, it needs to be stable for us to survive. So if we were high all the time, what would happen is we wouldn’t be able to detect danger, and we wouldn’t be able to detect good news like a potential mate or something valuable happening like a pot of honey, because we’d just be kind of sitting on the forest floor or the couch nice and happy and content doing nothing. So in order to detect when good things happen, or for that matter, bad things, something dangerous could come about. But if you’re stoned, you’re not going to notice. In order to detect those things, which is necessary for our survival, we have to have a baseline to see the difference from.

So if I ran into any of your listeners on the street and I said, “How are you doing today?” And they said, “Oh, I’m fine.” That’s our neutral state. My neutral state might not be your neutral state or somebody else’s, but we all know kind of like the baseline. And then if something changes that, something good or bad, we have a change then. So we can say, “Oh, something great happened today,” or something not so good. And that’s critical to survival. So the brain is all about defending that neutral state. And as soon as we take a drug that changes our neutral state to positive, which is the whole point of the drug, the very first time we try it, the brain begins adapting to counteract it. And always in every case, the brain adapts to produce the exact opposite state that the drug produced.

So if I take a drug to wake up and feel alert and aroused, my brain is going to produce a state of sleepiness and lethargy. So I need the drug to feel normal now. If I take a drug to feel relaxed and calm like alcohol or benzo or something, my brain is going to produce a state of agitation and irritation, and I won’t be able to sleep without it or relax without it. If I take a drug to not feel pain, to feel nice and relaxed and comfortable and pain-free, discomfort free, my brain is going to produce a state of intense discomfort and misery really, psychological and physical misery. So in every case, the consequence of regular use is that the brain gets better and better at adapting. It’s its sort of main expertise, adapting. And it counteracts the effect of drugs, and that means that I need the drug to feel normal, and when I don’t take it, I’m withdrawing, which is awful. And so I have to keep taking it, which is the whole meaning of addiction.

Christin Thieme: It’s fascinating how our brains respond. Addiction, obviously, we know is a very complex issue and it affects not only the individual, but also their family and the community. How do you think a better understanding of the neuroscience of addiction can lead to more effective prevention and treatment strategies?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Well, first of all, the neuroscience is perfectly clear. It’s not that people are not smart enough or strong enough or determined enough to fly straight. We are different, and some of us are much more susceptible than others. So the neuroscience should first of all, make us more compassionate and more understanding. But I think we need to go beyond that because another really, maybe equally important point about what we know about neuroscience is that addiction is caused by the brain adapting, and the recovery is also caused by the brain adapting. So the brain is amazing at adapting, just nothing like it, and it will if it has support. And so just like addiction can develop, recovery can develop. And so we shouldn’t give up hope on people, on anybody, but it’s hard to do on your own.

So in my own case, I ended up in this treatment center. I then went to a halfway house for 90 days. I had a lot of support. I had therapy. I had dental appointments. I mean, I had help. And my brain doesn’t adapt overnight, and it definitely didn’t. In fact, I’ve been clean and sober almost 40 years, and some people, like my parents and spouse would say, it’s still getting better, but it takes time. But it also takes a village a little bit. So not only do people need compassion, but they need incentive and encouragement. And the incentive part, if I have time, I’d love to come back to, because what we’ve tried in the past is to punish or shame people, you know, “Just get your act together.” Or, “You’re going to jail if you don’t get your act together.” Neither of those things work at all. It’s very clear. The war on drugs is complete failure.

But one of the things about people like me is I really am turned on in a kind of hyper way by excitement, by novel things, by interest. I have a tolerance, I have such a low tolerance for boredom, it’s ridiculous, which is why I like drugs. On the other hand, it’s why I like graduate school and neuroscience because it’s always new. So I think recognizing that we can turn our liabilities into assets and with the right kind of framing. So it might be that it doesn’t work well to say, “Don’t use drugs, and here’s your job as a cashier somewhere.” But it might help to say, “If you don’t use, there are these rewards.” You can travel to Fiji and you also can make better music or better art, or you can become a scientist or you can… I think having hope for growth and change is critical.

Christin Thieme: Would those incentives be some of the practical applications you would suggest? I mean, given your research and other research that you’ve studied, how can we practically apply those findings to inform treatment policy support for people who are struggling with addiction?

Dr. Judy Grisel: It turns out that we don’t, as a culture, really incentivize recovery. We punish addiction, but we don’t incentivize recovery. So I think having opportunities as I did to get better and help to do it is really critical. It turns out that if you tell a cocaine addict, “Don’t spend your rent money on this,” it doesn’t work. But if you say to them, “If you have some clean, new ways, you’re going to win Amazon gift cards or Walmart gift cards. And the more clean you are, the bigger the amount is going to get.” It’s kind of the opposite of what you think. You can start out small, but we’re very repetitive. So in other words, we like the carrot. What can I maybe win or how can I benefit? And that sort of thing is a big driver.

So I don’t think we do enough incentivizing, but also for kids who are mostly the ones falling into addiction, it’s good to recognize that they’re biologically primed for risk-taking, novelty seeking, disobedience for good reason. They’re kind of built this way as adolescents, which is why they’re sitting ducks for drugs and addiction. But they could also be great candidates for rock climbing or other kinds of physical or cognitive mental adventures, for learning surfing, or learning how to play the guitar. So I think that we need to not have vacuums. If there’s nothing to do that’s interesting, people like me are going to find something to do. So let’s make plenty of interesting things available, especially to kids that are not self-destructing.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, there it is. The case against boredom. I like it.

Dr. Judy Grisel: Exactly. I haven’t been bored in years, by the way.

Christin Thieme: Yeah. That’s right. In all of your experience, what do you think the biggest misconceptions about addiction are that you encounter and how can we work to dispel them as a society?

Dr. Judy Grisel: I think maybe the biggest misconception from people on the other side is that people with substance use disorders are refusing or just not willing to change. I don’t think that’s what it is, actually. I think, at least for me, I felt unable to change. I felt really, really stuck. I felt like I didn’t know how to live without drugs, and I knew I was dying with them. So the very thing that made my life possible was killing me, and I felt like there was no way out, and I had no idea of a way out.

And so what treatment and a halfway house did, so this is time, supportive time in a safe place. What that did is it gave me a little space so that I could begin to appreciate, wow, I do have a choice here. There is a way, small steps. I could never imagine where I am today, of course. But I think that it’s not that people don’t want to, it’s that they don’t know how and they need help and love and support. And when I say support, I mean like money, actual support, not just pats on the back, but assistance to get jobs, assistance to get apartments, feel good about themselves.

Christin Thieme: So for those who are dealing with addiction, individuals or families, what advice or resources would you point people toward to help them navigate the challenge more effectively?

Dr. Judy Grisel: Well, so extremes I don’t think are going to help. The extremes of either punishment and threats. We have 80 years clearly showing that does nothing. But I also think for family members and community members, it wouldn’t have helped me if someone had said, “Oh, geez, she’s just so pathetic.” I mean, I really was pathetic by the way. But if they had said, “Gee, you know, the best you can do is this,” so let’s just sell me short. So I don’t think we should sell people short. I think it’s something in the middle. It’s something about seeing them as they are and loving them, but also supporting them to change with some traction, not just, again, pats on the back, but what would it take?

And so for me, this time away from dealers and DEA agents and everything that were happening was helpful and really the way I’m alive and then I was able to go to school, I was able to slowly build a life back. It is like climbing out of a pit. So it doesn’t really help to throw bread and water down into the pit because I don’t want to stay there, really. But it also doesn’t help to put the bars over the top of the pit. It’s something about encouraging people to do the hard, slow work of getting out and encouraging, again with some practical aid.

Christin Thieme: As someone who’s deeply engaged in this field, what is one thing that a listener could do who maybe doesn’t know somebody firsthand who’s experiencing addiction, but they want to better understand, they want to better help address addiction in our country? What would be one thing that you would point people toward today?

Dr. Judy Grisel: It’s interesting. I can’t imagine there’s anybody alive on the planet who doesn’t know somebody who’s suffering.

Christin Thieme: It’s very true.

Dr. Judy Grisel: Ten thousand people every single day die from excessive drug use. Five percent of the people who die today are dying from alcohol use, excessive alcohol use. So it’s so prevalent. But you could go to a detox center. You could go to a jail and visit. You could go to open 12-Step meeting, an AA or NA meeting and just listen, I think meet these people. In fact, you can go probably right outside your house, onto the street and sit down and look in someone’s eyes. And it’s hard to do. It is hard to do because they don’t look good, and our tendency is to look away. But I think that’s making the problem worse.

Christin Thieme: Stop looking away and listen. Good advice for today. Well, Dr. Grisel, thank you so much for sharing with us. Thank you for giving us your insight and for all of the work that you’re doing.

Dr. Judy Grisel: You’re welcome, Christin. Nice to be here.

Additional resources:

- See how The Salvation Army supports rehabilitation.

- Watch Dr. Judy Grisel’s TED Talk, “Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction.”

- Read “Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction” (Anchor Books, 2020) by Dr. Judy Grisel.

- Start your day with goodness. Get on the list for Good Words from the Good Word and get a boost of inspiration in 1 minute a day with a daily affirmation from Scripture sent straight to your inbox. A pep-talk for the day. A boost of inspiration and comfort. A bit of encouragement when you need it. Get on the list and start receiving what you need today.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.