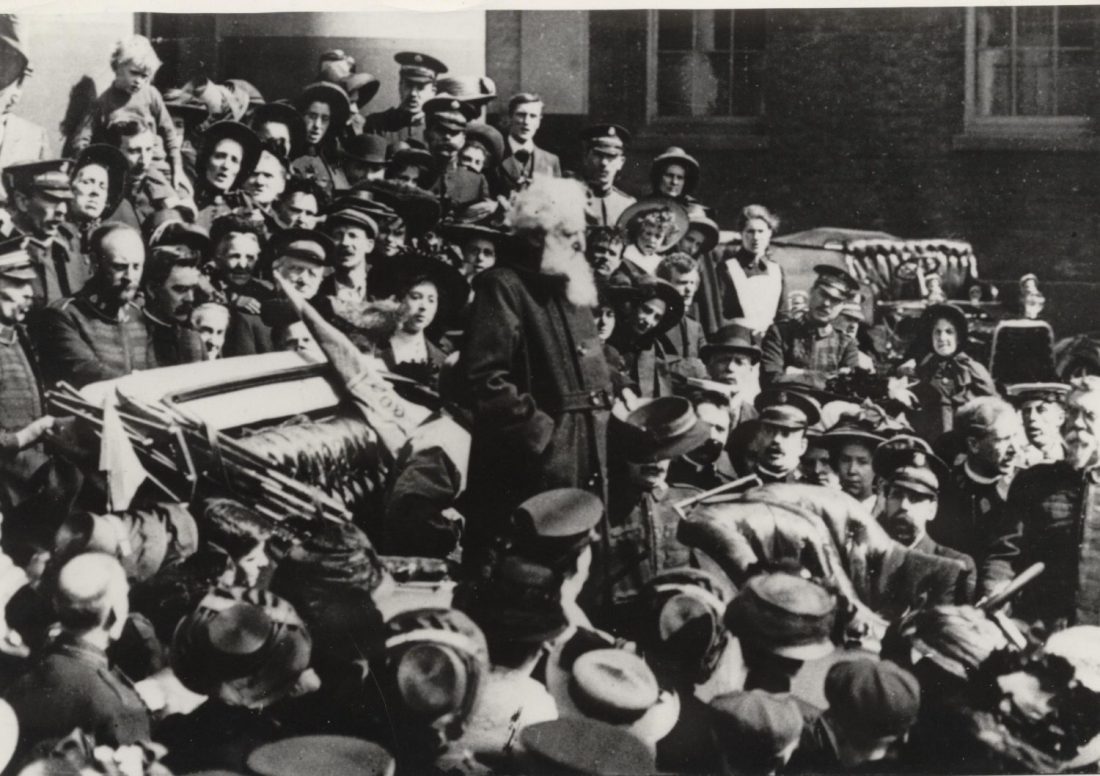

A tribute to the Founder at the centennial of his death.

By Diane Winston—

“Do something!” William Booth told his son Bramwell in the apocryphal story of the night when the Salvationist leader saw homeless men huddled under the London Bridge. Booth was a man of action whose desire to save souls was spelled out in deeds rather than theological tomes.

But in this centennial of Booth’s passing, the Founder’s beliefs are worth rehearsing as a way to reflect on his significance not only for the 20th century but for the 21st as well.

Booth was steeped in the holiness movement of the time. That meant he believed in sanctification, a second baptism that Christians hoped would enable them to overcome evil, work for good and help bring about the Second Coming. Booth expected that the redemptive work of his Salvation Army would bring about the Kingdom of God in his lifetime.

Likewise, Booth was convinced that the secular could be sacred. He urged his soldiers to preach in taverns and to use popular tunes for their hymns. He encouraged them to freely borrow from secular culture not only as a means to attract sinners but also to demonstrate that all of the world could be hallowed. This drove pious Christians crazy. They ranted against the Army’s appropriation of popular entertainment. They feared the movement was both corrupt and corrupting.

But Booth trusted that his Army was corporately called to do God’s work and that institutions as well as individuals could be sanctified. The Army was in the world but not of it, set apart by its garb, its service and its regulated community. The template for godliness was the Army field book of Orders and Regulations, which spelled out all aspects of Salvationist life, enabling Booth’s followers to maintain a sanctified life in a yet-to be redeemed world.

Following Jesus’ example, “Whatsoever you do to the least of my brothers that you do to me also,” Booth instructed followers to work in the public sphere. Jesus called on the faithful to redeem public life. Salvationists sought to effect this redemption with soup, soap and salvation. Soup, the first step, meant addressing material needs. Booth reminds us that the most basic expression of faith in public life is taking care of one another—feeding, nursing, sheltering and sustaining physical beings that are made in God’s image.

If this seems axiomatic, then recall that in Booth’s day, there were no food stamps and very few soup kitchens. Homeless shelters were practically nonexistent, neither were there many programs for job training. The poor were not welcome in most churches, and society had no concept of a social safety net.

Booth was not alone in advocating church involvement in social welfare work. A growing number of religious folks on both sides of the Atlantic were experimenting with how best to deliver services. One ongoing debate was whether food and clothing should be given out at missions or churches, or if the poor should be institutionalized and receive aid in a place like an orphanage or almshouse that concretized their outcast status.

That was not Booth’s way. The poor were the heart of his mission, and his own experience had shown him that poverty could be overcome with the right application of material aid and divine blessing. The majority of Booth’s fellow Christians assumed that the poor were responsible for their plight, and that their deepest desire was to live off the dole. Accordingly, the Army’s program, which offered help to all those who asked, seemed alarmingly naive.

Yet if offering soup seemed ingenuous, providing soap was excessive. Soap in this usage is recognition of human dignity that goes beyond providing basic services. Soap is not a material necessity; rather it signifies recognition of another’s intrinsic value. During Booth’s time, charity organizations were obsessed with evaluating the poor. Their aim was to separate the undeserving from the deserving poor. “Scientific” reformers worried more about supporting scam artists and “pauperizing” recipients—that is creating a permanent underclass supported by indiscriminate charity—than relieving suffering. Accordingly, charitable societies kept busy determining who was truly needy.

The Army refused to engage in this process. Instead it helped anyone who asked. But Salvationists expected something in return. If someone wanted a meal or bed and could not afford to pay, they were invited to work for their keep. According to their motto, “if a man is willing to work, he is worthy of being helped.”

Of course, the Army was not content just to help the physical man or woman. Its ultimate aim was saving his or her soul. William Booth never lost sight of his mission—without eternal salvation the earthly relief was a fleeting redress. That’s why religion was central to public life. For a post-millennialist like Booth, there was no separation between sacred and secular. Booth’s faith shaped his understanding of public life so completely that he could not see a seam distinguishing the two.

Booth’s legacy is first and foremost his Army that, in its early years, was peopled by religious radicals, youthful idealists, ardent evangelicals and even socialists. Booth commanded them to “attract attention” but today’s 1.1 million member worldwide Army rarely does. For Americans today, the Army largely remains hidden in plain sight. It’s seen at Christmas when shoppers slip coins in the kettle, but most are unaware of the Army’s evangelical identity, much less its holistic theology.

For many Americans, Booth’s legacy, particularly his understanding of the role of religion in shaping public life, might be a welcome message. Booth believed it was incumbent upon believers to participate in public life—after all, it was their responsibility to usher in the Second Coming. But it’s important to remember what he wanted his followers to do.

Booth didn’t want his soldiers to debate policy, taunt opponents, lobby officials or pursue electoral politics. He wanted Christians who were willing to do the unsung work of caring for others. Booth believed in a daily commitment to eradicating injustice, inequality and poverty.

Because he sought a perfected world, a world ready to welcome Jesus, Booth taught that faith should be enacted in the public sphere. Regardless of whether or not Americans accept his particular theology, surely we can see the merit of believing that our human efforts can bring about positive change.

Do Good:

- What’s The Salvation Army’s story since its founding in 1865? Follow along here.

- Read more about the Booth family in “Those Incredible Booths: William and Catherine Booth as parents and the life stories of their eight children” by General John Larsson (Ret.).

- Visit westernusa.salvationarmy.org to find The Salvation Army nearest you.

- Give to support the fight for good in your community.