Rising incivility has put many Americans on edge. What roles can Christians play in bringing peace to the public sphere?

Blogger David Gushee took a month-long hiatus this summer from his column Christians, Conflict & Change for the Religion News Service. A prolific writer, Mercer University professor and president-elect of the Society of Christian Ethics, Gushee had long held a front row seat to the hostility that has infected many of our national conversations. “Sometimes the best response to all the world’s ugly noise is a retreat into silence,” he wrote in his sign off.

“I needed a chance to think of some new ways of engaging the distressing circumstances that we’re witnessing,” he said in an interview with Caring. “What I was seeing in myself was unhealthy levels of cynicism and near despair over the state of our politics. And to some extent over Christians getting stuck in arguments along left and right lines over everything.”

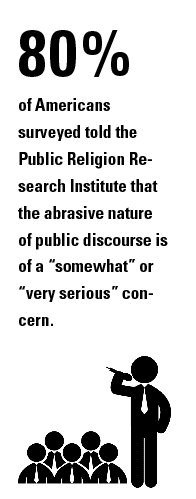

Gushee isn’t the only one who’s had enough of the bickering. Rising incivility has had an unsettling effect on Americans, over 80 percent of whom in a 2014 survey told the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) that the abrasive nature of public discourse is of a “somewhat” or “very serious concern.” And that was long before the 2016 election cycle entered its final combative months.

Gushee isn’t the only one who’s had enough of the bickering. Rising incivility has had an unsettling effect on Americans, over 80 percent of whom in a 2014 survey told the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) that the abrasive nature of public discourse is of a “somewhat” or “very serious concern.” And that was long before the 2016 election cycle entered its final combative months.

Indeed, “this particular campaign in the U.S. has been a wakeup call,” said Richard Mouw, an ethics professor and president emeritus at Fuller Theological Seminary. Speaking in a May 2016 podcast with Leith Anderson, president of the National Association of Evangelicals, Mouw went on to warn of a “failure of what we used to call catechesis,” in which churches have in some ways fallen down on the job of instructing congregants on how to remain kindly disposed toward those with whom they disagree. Such thoughts must have been weighing on Mouw’s mind for some time—way back in the 90s, he wrote a book exploring biblically-based consideration, “Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World” (Intervarsity Press, 1992).

For anyone who goes looking, there’s much ancient insight into present circumstances. The delicate negotiations around how we can be different together weren’t foreign concepts to the earliest Christians, and the New Testament is in many ways a document of how humans have wrestled with thorny questions about what it means to be simultaneously children of their one true God and people in a diverse world.

“We see that the church is born within the context of a really complex, pluralistic world and negotiating that has been a challenge from the very get-go,” said Dr. James Read, executive director of The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg, Canada. “The shape it takes in our time is unique to our time, but the challenges and the questions are not.”

The Bible is peppered with wisdom on how to bring peace, reconciliation and justice to an often contentious civic sphere. There’s the exhortation in Jeremiah 29:7 to seek the peace of the city whither I have caused you to be carried away captives, and Matthew 22:35-40 on loving thy neighbor as second only to loving God. Readers can consult Isaiah 10:1-4 and Amos 2:6-7 for passages proclaiming divine judgement against those who would use government might to crush the poor and allow society to abuse the vulnerable, and while 1 Peter 3:15 famously reminds Christians to be ready at all times to proclaim their faith, do this with gentleness and respect, it adds.

But recent research indicates that it’s not simply the message, but also the medium that helps set the tone. That religiously engaged people tend to be civically engaged people has been widely documented. In 2010, two political scientists—Robert Putnam from Harvard University and Notre Dame’s David Campbell—explored that connection in depth with their book “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us” (Simon & Schuster, 2010). Among their findings, Putnam and Campbell learned that it’s not simply religious Americans, but rather religious Americans with strong social ties who were most likely to respond generously to their wider communities, in realms both secular and sacred. The very nature of congregating plays a subtle but powerful role in this. Particularly in America, congregations have acted as de facto community centers, and the idea that religious communities are laboratories for teaching social relationships was also present from Christianity’s earliest days.

While 1 Peter 3:15 famously reminds Christians to be ready at all times to proclaim their faith, do this with gentleness and respect, it adds.

“Let’s remember that the Greek word that’s been translated ‘church,’ generally speaking, is the word ‘ecclesia,’ which…came from a political context meaning a place of assembly, a kind of town hall,” Read said. “They were to be places in which you learned what it was to be, to work collaboratively with other people, where there will be greater or lesser degrees of unanimity of opinion. Certainly as I understand it, the church is to be a cradle for the nurturing of a kind of civic responsibility and privilege that extends beyond the biological family bounds.”

Putnam and Campbell also identified something unique to religiously-based social networks—the “moral freight” they carry, a phenomenon that compounds their influence. As they put it, “hanging out with gym rats is likely to increase your concern about fitness, and in the same way hanging out with religious do-gooders is likely to increase your own motivation to do good.”

Doing so also pairs the motive with the means and the opportunity, said Brie Loskota, executive director of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California. “If you pair the operating philosophy of a theology that says you should be generous or it’s your job to make the world a better place with the opportunity, through an institutional vehicle like a congregation, to actually act, it’s a lot easier than to have an abstract notion that ‘I should do good’ without a place in which I can do good,” Loskota said.

But what happens when the idea of good itself becomes a political football?

“A 2000-year-old Christian tradition ought to be able to transcend a particular left-right cultural and political polarization that I think is only really about 50 years old in the U.S.,” Gushee said.

So while logged off, he decided to take a deeper dive into Christianity’s spiritual, moral and theological resources, far from the madding crowd of social media and the blogosphere. That he found sustenance in prepping for his class on history’s great moral leaders and the “very dear community” at his church wasn’t too much of a revelation. But something else was—a centering that came along with the simple rhythm of the lectionary, the repetition of the Nicene Creed. In other words, just as important as what he was reading was the context around it. Uncoupled from the news cycle, Gushee says he found comfort in reconnecting with the eternal story of the church, distinct from the story told by American culture.

– Explore the American Values Atlas and other research from the Public Religion Research Institute at prri.org. – Follow David Gushee’s column, Christians, Conflict & Change, with the Religion News Service at religionnews.com/

columns/david-gushee

In fact, one of the most powerful ways religion can enrich the public sphere is its ability to elevate a sense of collective humanity beyond the very worldly game of politics, creating a shared space outside the political arena to come together and embody better angels. Faith-based disaster relief can be an excellent example of this, according to Loskota. The act of ministering to each other’s suffering opens up a civic space in which people can make profound connections based on a shared belief in the sanctity of life, not ideology. Moreover, Loskota points out, research shows that the healing from trauma actually happens in community.

Quiet self-examination, on the other hand, happens, well, quietly, and by one’s self. What’s missing in much of the demonizing that drives incivility is often a clear-eyed appraisal of our own individual culpability. As Mouw said to Anderson, the anchoring that comes from honest soul searching can go a long way toward soothing the urge to fan the flames of heated debates.

There’s a verse about that too: Search me, O God, and know my heart: try me, and know my thoughts: and see if there be any wicked way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting (Ps. 139:23-24).