Art helped a former Los Angeles gang member find God

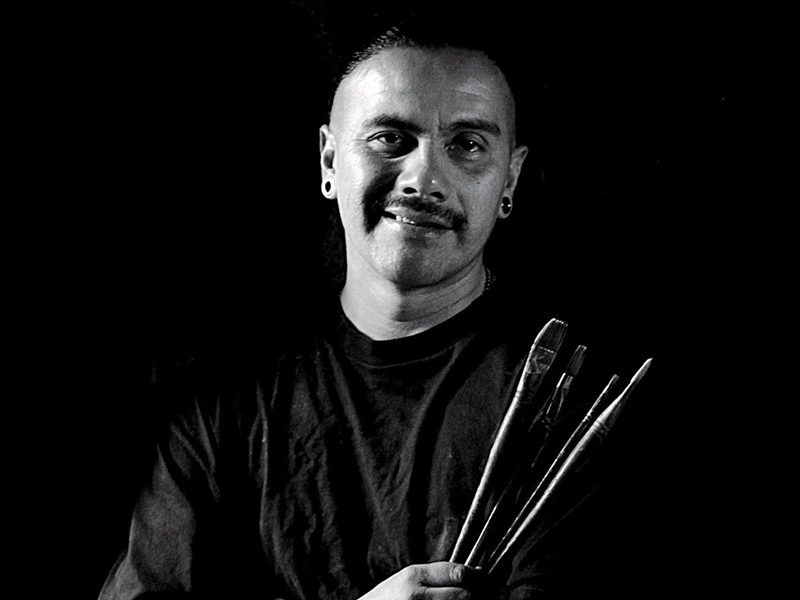

It wasn’t until the beating stopped that 12-year-old Fabian Debora realized he was officially a gang member.

“Covered in blood I walked over to my cousin and told him that they jumped me in,” Debora said. “I didn’t want to gang bang, but I didn’t know what to do.”

Debora grew up in Boyle Heights, one of Los Angeles’ poorest communities. His family had come to the U.S. in search of the American Dream, relocating from Juarez, Mexico, first to El Paso, Texas, before settling in Southern California in 1980.

“It was very difficult for my parents to gain employment and opportunities because of their immigration status,” Debora said. “My mother and father were no longer smiling, happy, or in love.” Instead, he says, they felt overwhelmed by the need to provide for their only child.

To do that, Debora’s father began smuggling drugs from Mexico to the United States.

“My mother wasn’t approving,” Debora said. “He would ask my mother, ‘You want to survive, right? You want to eat, right?’”

Domestic violence, abuse and neglect soon became part of the household routine, he said. Slowly, Debora began to blame himself for the situation.

“I thought, maybe if I wouldn’t have been born, my father’s and my mom’s life would have been a lot better,” he said.

Then one day while hiding under a coffee table, as his mother screamed in the background, Debora began to draw. “I discovered this gift of art,” he said. “Art to me was something that gave me meaning, it gave me hope, it gave me self-worth.”

Debora continued to explore his desire to create art. He would draw during class while attending Dolores Mission Elementary School.

On many occasions he would find himself in the principal’s office. His teachers would chastise him for drawing instead of doing his schoolwork, but he would continue. “If you would ask me to do my math it would be: two plus two equals four, four plus four equals a drawing,” he said.

In the eighth grade, his life took a turn. With only two weeks left until graduation, Debora found himself facing off with an angry teacher.

“He came around the classroom, and he grabbed my artwork, put it in front of me, and he tore it in half,” Debora said. “That was my gift, my self-worth, my hope. He literally ripped my heart in half—the way I felt when I first caught my father putting a syringe into his left arm.”

It felt like one betrayal too many.

“I was betrayed by my father because of heroin, was betrayed by my mother who couldn’t protect me from my father, and now the teachers,” he said. After throwing a desk at the teacher from across the classroom, Debora was expelled. With his chance at graduation went his mother’s hope for a better life for her son.

Debora was sent to meet Father Greg Boyle, the founder of Homeboy Industries, one of the largest gang intervention programs in the country.

“Father Greg said to me, ‘I want you to go home and draw me something,’” Debora said. “And that’s when I recognized Father Greg acknowledged my gift of art. And that’s when he became my father figure.”

Soon, Debora was creating graffiti art in the L.A. River, his “playground.” On his way home from there one night, Debora was approached by a group of neighborhood gang members.

“I told them ‘I don’t bang,’” he said. “They didn’t like that, so they punched me.”

But soon, Debora gravitated to the gang, not fully understanding the implications of membership and attracted to the attention they gave him.

“The reality was that because of my very low self-esteem…I fell for them,” he said.

It was to become a period of Debora’s life punctuated by multiple arrests and months in jails around the city. He began to use drugs—a mix of marijuana and crack cocaine.

But eventually gang culture began to lose some of its allure, and in 1994, he decided to call it quits.

“I walked away, but I found myself to be abandoned, neglected and rejected [again],” he said. “So then what better way to not feel that then by using drugs again.”

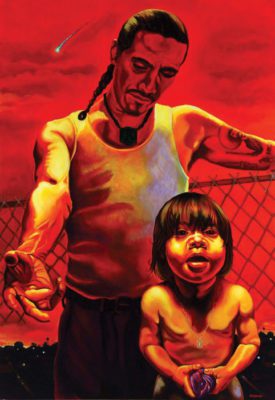

Soon after, Debora became a father. Fabian Jr. was born but quickly taken away by his mother. Again, Debora turned to drugs.

This time it was methamphetamines.

“I could not believe in recovery. People would tell me, ‘Jesus loves you’ and I used to say, ‘Well if he did then why is my father a heroin addict, and why is my mom struggling, and why do I feel this way?’” Debora said.

Depressed and addled by his addiction, Debora began to think about suicide. One day, after being caught by his mother high on meth, he just ran.

“I jumped into the Hollenbeck Park pond. Hot, oily, and greasy and full of seaweed, I ran toward the freeway and I walked on the edge, jumped onto it and bit my tongue, practically ripped it open,” he said. He began to hear voices in his head.

“It became amplified as if they were screaming at me from the universe,” Debora said. “‘Kill yourself, kill yourself.’ It sounds so attractive at first and then…it started to become terrifying as if it was pushing me toward the road.”

Debora began to hear the trucks passing. “The voice got louder and I couldn’t deal with it,” Debora said. He covered his ears with both hands, averted his gaze “and I ran.”

He survived. Sitting on the center divider of the freeway he looked up.

“I saw the sun reach down to me beautifully and I receive the feelings of peace, joy, happiness, and serenity,” he said. “Those feelings that can only come from a higher being, a higher source; my God. That day I understood that every son must return to his father. That day I did, and the thought of my children was the purpose, and why he allowed me to live.”

Debora was met by authorities, guns drawn, on the freeway. Racing off, he found a payphone a few blocks away from which he could call his mother to pick him up.

“I told my mother, ‘I think I have a drug problem,’” he said.

With expletives she replied, “I’ve been trying to tell you this for the past 15 years.”

Three days later, Debora walked into The Salvation Army in Pasadena, Calif., to begin his 12-step program.

“I recognized that there was a God,” he said. “I’d become a spiritual believer, a firm believer, because it was only through grace that I survived that day on the freeway.”

Debora sailed full force through the adult rehabilitation center program. He graduated, and within days began working at Homeboy Industries under the supervision of Father Greg. He returned to school and today works as the director of substance abuse services at Homeboy.

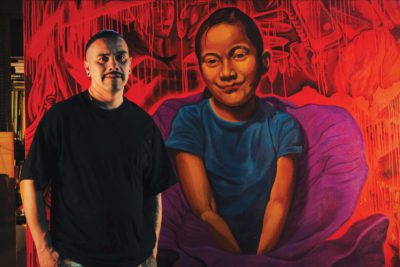

He continues to create art. A number of Debora’s murals can be seen throughout Los Angeles, including inside the city’s airport, on the streets of Boyle Heights, and displayed at Marvin Gay Studios.

“Art…is what kept me in tact. It was my hope, a reflection of my hope and my challenge,” he said. “Art kept me at ease, art gave me a sense of hope, it gave me self-worth.”