An excerpt from “The Hope in Our Scars: Finding the Bride of Christ in the Underground of Disillusionment”

Why do so many go through the motions of church life, often falling short of entering and living in the world of new life in Christ with all our senses? Why do we struggle to be known? Shame isn’t only something we experience from others. We are pretty good at shaming ourselves. Shame tells a tale about your value. It speaks to who you are and says, “You’re not good enough.” Researcher and author Brené Brown says we can easily fill in the blanks when we think we don’t measure up: not smart enough, not successful enough, not attractive enough, not skinny enough, not healthy enough, not spiritual enough.

We are particularly good at covering up on Sunday mornings. My friend calls it “church face.”

We all know that the gremlins can be more exacerbating on our way to church. Those coming alone battle how this is magnified in worship. The messages from their own narrating selves are compounded by a heightened sense of their aloneness among other Christians. Talk about disillusionment! How is it that our brothers and sisters in worship can make one feel so isolated? Like you don’t measure up to the contemporary gospel ideal of the nuclear family?

Maybe you have your act together on Sunday morning. But you still probably have a bit of church face. The Sunday morning hustle is a safer example. We don’t share our stories. We don’t tell our secrets. We can’t be vulnerable. There’s the wife who walked out on her family to the surprise of everyone in church.

“She was struggling? Did you know? Me neither!”

There’s the high school senior who is full of doubt about God. Quietly. Outwardly, she answers the questions “correctly” in Sunday School. There’s the man who had a panic attack on Friday and is terrified it may happen again while trapped in worship. The person sitting next to you doesn’t have job security and is afraid to ask for help. No one seems to even engage with the single woman in her late thirties. She feels so alone in God’s household. Many of us do. We’re all just smiling because we should be further along on the sanctification scale by now. There’s that word should again. Shame and should go hand in hand. We let our awful narrating selves make us feel like imposters who don’t have what it takes. We must be vulnerable to be known, and that can be terrifying. What if church is not a safe place to be known? We need to talk about the masks we wear and the silence we keep.

The very thing that we long for we run from. We long to see and feel that gaze and hear, “You are absolutely beautiful, my darling; there is no imperfection in you” (Song 4:7). It is an expression where Christ recognizes himself in his bride, like Adam, “This one, at last, is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh” (Gen. 2:23). At last. We long to be looked upon and recognized this way now because our hearts long for this greater fulfillment in eternity.

We want a kind of love that sees us in our most vulnerable condition—soul-naked—and embraces us. But we struggle to believe this kind of thing is real. Being soul-naked, or physically naked even in the most godly, intimate conditions, leaves us vulnerable. We are often uncomfortable there. And we run from the gaze that we long for—before friends and family in baring our souls, before spouses in romantic intimacy, and before God. It can terrify us. So we put on the masks. When you look at a group picture that you are in, who is the first person you zone in on? Yourself, right? How do I look? How do others see me? Maybe you stay at the superficial appearance, but maybe you look deeper. What is my expression saying? What story am I telling? How am I? There you are, captured in a moment, for the gaze of yourself and all others looking. Tension pulls between wanting to be seen and the anxiety of being seen. Sometimes we notice the mask we were wearing.

How do you want to be seen? What story do you want others to hear about your life? Maybe you haven’t asked this question directly, but we are hustling to curate our story all the time in our curated social media accounts, our wardrobes and our interactions.

Here’s a similar yet deeply different question: What do you think people see when they look at you? What story are they telling themselves about you? This is something we cannot control. Some agonize over this, and others completely block the thought out, either choosing to believe most people accept the story they present or pretending other people don’t care because thinking otherwise is too devastating to bear.

That leads to the next question: How are you? What’s your real story? Sometimes this weighs on us when we are alone, undistracted. Do you know another time we feel it weighing down? When someone is really looking at us. You know what I mean. Sometimes we can feel the gaze before we make eye contact. What is that sense that we have? I’m not sure how we “feel” a gaze, but most of us have. And we all know that there are boundaries with how we look at each other—I’m not merely talking about sexual propriety, but social awkwardness. Every now and then, and not in a creepy way, someone really looks at us. It can be uncomfortable. More often than not, we look away, wanting them to look away. In that moment you are feeling seen in a way that asks these very questions: How are you? What is your real story? We want it deeply, but it terrifies us.

Shame is the cause. Since the fall, “to be human is to be infected with this phenomenon we call shame,” as Curt Thompson puts it. So if someone is really looking at you, your thoughts might be, “You will not measure up. How could anyone possibly love you if they knew the real you?” Our adversary leverages shame to keep us alone and entrapped in sin. It’s so dark and ugly—how can we be involved in creating beauty? In resurrection? Some of the shame is from what others have done to us, and some is of our own doing. So many people carry shame and trauma from abuse or neglect. Shame entraps us with messages about our value and diminishes our sense of self. If the people we love knew what was going on in our minds and the things we have done or that have been done to us—the very real sin that is such a violation of beauty, truth and goodness—they would need to look away. We can’t bear the gaze that we long for because we do not see ourselves as worthy.

So we get stuck in patterns of depression, isolation and sin. When we think of the stain of what has been done to us in abuse or neglect or what we have done to ourselves and others in sin, we struggle to see a way forward. Shame sticks to us, in a sense. How can we talk about beauty now? You can’t exercise shame off with the story you are hustling; it doesn’t work.

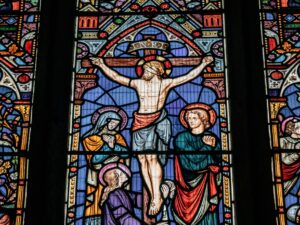

The good news is that God comes for us. And so we need to consider Christ’s bearing our shame on the cross, despising it, while the Father looked at him (Heb. 12:2). And we need to rejoice in what God sees when he beholds us now.

Taken from “The Hope in Our Scars: Finding the Bride of Christ in the Underground of Disillusionment” by Aimee Byrd. Copyright © 2024 by Aimee Byrd. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.harpercollinschristian.com

Do Good:

- Read “The Hope in Our Scars: Finding the Bride of Christ in the Underground of Disillusionment” (Zondervan, 2024) by Aimee Byrd.

- Get on the list for Good Words from the Good Word and get a boost of inspiration in 1 minute a day with a daily affirmation from Scripture list this sent straight to your inbox. It’s an email to help you start your day with goodness.