Julian of Norwich seems an improbable guide in the 21st century. We orbit the earth. She spent her life in one small room. But she knew the message God gave her was not meant only for her. “I would to God it were known, and my fellow Christians helped on to loathing of sin and loving of God,” she wrote. “This sight was shown for all the world.”

Julian was given that sight because she prayed. Most of us pray for good health. Julian prayed for an illness in which she and everyone else would think she was dying. She prayed to be present at the crucifixion, another unusual request. And above all she prayed for compassion, repentance and longing for God. She made the first two requests “if it is your will,” but she prayed for the last without any conditions.

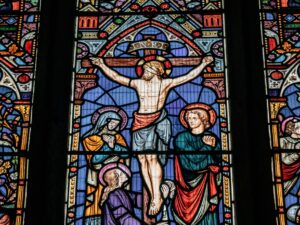

And in May 1373, when she was 30 years old, all her prayers were granted. She became so ill that her priest was sent for to give her the last rites. As he held the crucifix before her eyes it seemed to her that the cross began to bleed.

In that near-death experience she was given a series of “showings,” during which our Lord appeared to her and spoke with her. They lasted from four in the morning until past “none,” which could mean midday or 3 p.m., the time the office of the ninth hour is said.

These were given in three ways—by inward sight, by outward sight and by words formed in her mind. Each overlapped and complemented the other.

Julian got better and went to live in a little room beside St. Julian’s church in Norwich, where she spent the rest of her life meditating on what she had been shown, and writing it down.

At the time, there seemed little chance of our getting to read it, six centuries later. There was just her own handwritten copy and, if she asked a scribe to make another, there was a chance it might come to the official notice of the Church. And if that happened, there was a risk that both she and her book would be burnt.

Because many of the things she was shown did not appear to be the same as the teaching of the Church in her day. Julian was troubled by this:

“Now during all this time, from beginning to end, I had two different kinds of understanding. One was the endless, continuing love, with its assurance of safekeeping and salvation—for this was the message of all the Showings. The other was the day-to-day teaching of holy church, in which I had been taught and grounded beforehand, and which I understood and practised with all my heart” (Chapter 46).

“God himself showed me the higher judgement at that time—and therefore I must needs accept it. And the lower judgement was taught me by holy church—and therefore there was no way in which I could forsake the lower judgement… And I still stand in longing, and shall until I die, to understand—by grace—these two judgements as I ought to” (Chapter 45).

We are able to engage in these contradictions today because, by the grace of God, we are now less likely to react by retreating into our prepared positions and lobbing missiles at each other. Like the soldiers in the First World War who climbed out of their trenches and played football together on Christmas Day, we have to be prepared to venture into the no man’s land our sectarian squabbles have laid waste, and to recognize that there are no enemies, but only people like us. Today, after centuries of being handed round in secret, Julian’s book has emerged as one of the great guides to faith in the 21st century.

Julian invites us into her cell to join her in her search for understanding. This will not be easy, because once she went into her cell the entrance was sealed. But a solid barrier need be no obstacle to the world that lies beyond it, as Alice found when she stepped through the looking glass, and Harry Potter when he pushed his trolley through the wall that concealed Platform 9¾ at King’s Cross. There is a sure way to dissolve the wall that bars the entrance to Julian’s cell. It is prayer. And that is how we shall have to begin.

Prayer will let us join Julian in her cell. But where to begin? On Ash Wednesday we are given instructions: But when you pray, go into your room, close the door and pray to your Father, who is unseen. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you (Matt. 6:6).

But not many of us have a private room, and open plan means we increasingly share our space with other people. Sometimes the only room with a door is the bathroom.

Take heart. You can pray to God in the bathroom. You don’t have to wait for a special time and place. God is with us all the time, wherever we are. We just have to recognize it.

I grew up in an age when many people only had a weekly bath (and sometimes had to take turns in the bathwater) but now some people shower two or three times a day, so there are plenty of opportunities. Each time, you can remember your baptism. You can thank God for the gift of clean, pure water—not something to be taken for granted. You can stand naked before God—as naked as Christ at his crucifixion. And as you dress, you can remember God showed Julian:

“At this time our Lord showed me an inward sight of his homely loving. I saw that he is everything that is good and comforting to us. He is our clothing. In his love he wraps and holds us. He enfolds us in love and will never let us go” (Chapter 5).

But prayer begins when you first wake to a new day. One Lent I decided to give up 15 minutes in a warm bed each morning. I am a reluctant riser, but I dragged myself out of bed and prayed. It was the best thing I ever did.

Julian tells us that prayer is not one-sided. God is longing to hear from us.

“Our prayer makes God glad and happy. He wants it and waits for it so that, by his grace, he can make us as like him in condition as we are by creation. This is his blessed will . . . He is avid for our prayers continually” (Chapter 41).

All of us have known times when we have waited anxiously for a letter, or these days an email, to drop into the mailbox. The thought that God feels the same is a revelation, and so is the assurance that we often find praying hard work. Julian writes:

“So he says this: ‘Pray inwardly, even though you find no joy in it. For it does good, even though you feel nothing, see nothing—yes, even though you think you cannot pray. When you are dry and empty, sick and weak, your prayers please me—though there be little enough to please you. All believing prayer is precious to me.’ Because of the reward and endless thanks he longs to give us in return, he is avid for our prayers continually. God accepts the goodwill and work of his servants, no matter how we feel” (Chapter 41).

Praying can be hard work, and it also needs time. And finding time seems to get harder and harder in our busy world.

Adapted from “The Way of Julian of Norwich: A Prayer Journey Through Lent” (SPCK, 2021) by Sheila Upjohn. Used with permission.

Do Good:

- Read “The Way of Julian of Norwich: A Prayer Journey Through Lent” (SPCK, 2021) by Sheila Upjohn.

- See how you can get involved in the Fight for Good with The Salvation Army.