For the next few weeks, we’re talking about disasters. You’ve seen the headlines and news coverage of the wildfires, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, and heat waves plaguing our country. And according to experts, this troubling trend is showing no signs of leveling off.

In fact, the U.S. experienced a record number of billion-dollar weather disasters in 2023, according to a new report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. There were 28 separate events, surpassing the previous record of 22 set in 2020. These events cost $92.9 billion, and at least 492 fatalities.

Of course, this isn’t a one-year fluke. Looking at the bigger picture paints a frightening picture. In the last seven years alone, the U.S. has seen 137 billion-dollar disasters, causing more than a trillion dollars in damage and killing over 5,500 people.

Last year also saw a number of climate anomalies, including an above-average number of tornadoes, a record-high number of named Atlantic tropical cyclones, and widespread drought influenced by record heat.

In the face of this changing disaster landscape, there’s one organization consistently on the frontlines, bringing aid and hope to those in need: The Salvation Army, whose disaster relief operation never sleeps.

Last year alone, The Salvation Army served nearly 600,000 people across a staggering 4,300 disaster events. Thanks to the generosity of donors and corporate partners, The Salvation Army was able to provide these survivors with a warm meal, a safe haven for the night, and in some cases, something just as essential: a listening ear and a moment of prayer.

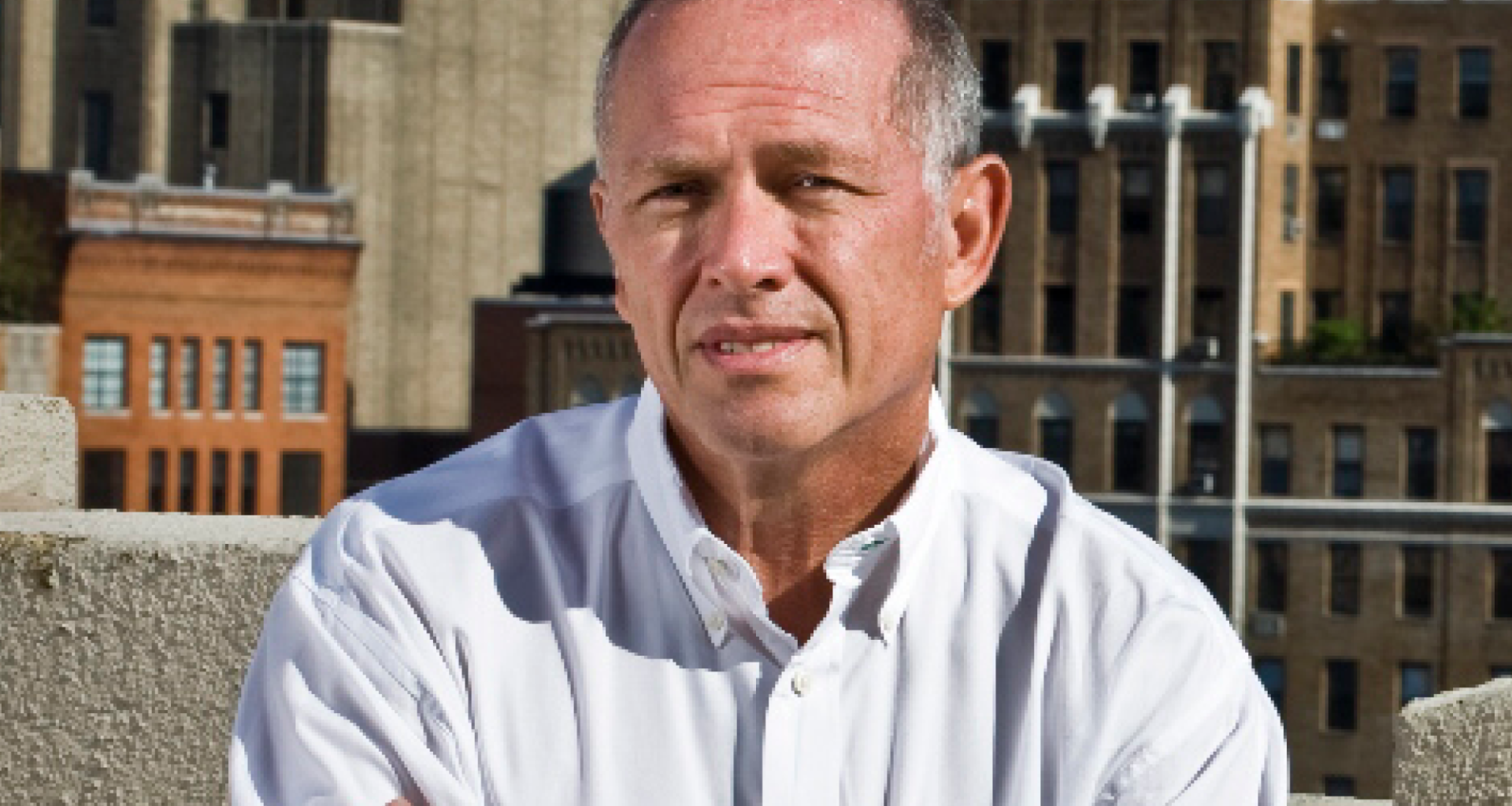

In this episode, John Berglund, The Salvation Army’s Emergency Disaster Services Director in the West, is helping us set the stage for our ongoing conversation about the current state of disaster relief. John’s been on the show before, but we love talking with him, and hearing his insights on the industry.

Today, he’s sharing more on the dynamics of serving throughout another record-breaking disaster year, the importance of cleverly adapting to meet needs, and some of the common misconceptions around disaster relief.

Show highlights include:

- The Salvation Army plays a crucial role in disaster response, meeting needs without discrimination in the aftermath of natural disasters.

- Partnerships, local involvement, and training are essential for effective disaster response.

- Disasters disproportionately affect low-income communities, and The Salvation Army focuses on addressing their needs.

- The psychological impact of disasters is often overlooked but is a core part of The Salvation Army’s response efforts.

- The Salvation Army is involved in both immediate relief and long-term recovery efforts.

- There are misconceptions about the nature of disaster relief and the ongoing work that happens behind the scenes.

- Individual and family preparedness is crucial in the face of increasing extreme weather events.

- Getting involved with The Salvation Army at the local level is the best way to support disaster relief efforts.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: Well, John, welcome back to The Do Gooders Podcast. Thank you for being here once again.

John Berglund: Christin, thanks. Thanks so much.

Christin Thieme: We are starting off this series talking about the state of disaster response for The Salvation Army. And I wanted to start with looking at this increase that we’ve seen in both the severity and the frequency of disasters in the US in particular. Of course, The Salvation Army has a long history of meeting needs without discrimination in the aftermath of natural disasters. How do you see The Salvation Army’s role?

John Berglund: Looking at this increase that we’ve seen in both the severity and the frequency of disasters in the US in particular, of course The Salvation Army has a long history of meeting needs without discrimination in the aftermath of natural disasters.

Christin Thieme: How do you see The Salvation Army’s role evolving in the face of the changing disaster patterns that we’re seeing?

John Berglund: Well, I think it’s going to continue. I think there’s a national expectation that The Salvation Army will be there to assist, much like we assist individuals on a daily basis, we’ll be there to assist communities as well as we can. I think the difference is, one, the media is very, very quick and very, very loud on these situations when they happen. The other thing is that the field is very competitive and very crowded. So unlike, say, 20 years ago, where there were only a number of major response agencies in the United States, nonprofit agencies, there’s hundreds and hundreds of them now. And there’s a lot of them that I would call boutique agencies that specialize in very specific areas of disaster response, like psychosocial support and such.

The Army has to continue to make it a priority that we’re going to continue to do disaster response. And with that, I mean to encourage our people to stay involved and connected on a local level, because I think that’s what’s the most important. If we’re not connected and we’re not involved on a local level with the disaster response agencies and local government, that’s where there will be gaps. I think the days of just rolling out canteens and showing up in one area or another, that still can easily exist. There’s no doubt about that. But it’s not as easy because the field has matured over the past 20 years or so. And it’s a well-oiled machine being led by government at all levels. And there’s also, years ago, you didn’t have the influx of non-profit or for-profit entities that have entered the field. So the field is multi-sector, it’s crowded, it’s competitive. The Army still holds a premier position in that and will continue to do so, but I think the key to that is that we continue to train and reinforce that we have to be connected at the local level.

Christin Thieme: When you talk about the field, for context for people listening who maybe aren’t as familiar, can you give us just a little bit of a picture of where does The Salvation Army fit into this apparatus and what is our role in the face of a disaster?

John Berglund: The Salvation Army has been an active player for many a year, especially in the feeding side. So we’ve been known as a primary agency to roll out the canteens, produce feeding and fill that niche. That has expanded. That’s expanded to psychosocial support, emotional and spiritual care. That’s expanded to donations management. That’s expanded to a lot of other gaps that we can fill. And I think the beauty of The Salvation Army, or one of the things that I’ve enjoyed over the years, is that often we can be incredibly agile. Meaning we can be in an emergency operating center at a local or state level and say, hey, you think the army just feeds, but we can also do this and we can also do that. So, even though disaster is our primary tenant, our strength is that we’re a major social service agency with a tremendous amount of presence throughout the country as well as assets, assets, whether they be in volunteers, whether they be in social services. So again, it’s one army, and The Salvation Army is known for its ability to ramp up the different resources that it’s had to meet the needs in a community.

Christin Thieme: So while the response efforts are such a well-oiled machine, like you say, we also see these trends basically of worsening weather patterns and worsening weather events that are causing issues for disasters. How are we preparing for or adapting to this future with these more extreme weather events?

John Berglund: Yeah, I agree. I do think we’re going to have more extreme events. And I think the role for the Army is to figure out the right niche in the different locations at the right times. We surely can’t do it all, and we can’t do it all on our own. So partnerships are really key. Again, I think I’ll keep going back to the local level. If the local level knows what the hazards are in its own community, if we’re working to mitigate those situations, we’re ahead of the game, but also partnerships, figuring out the best role for us, figuring out the best way to use the capacity. For example, in some communities, we may have more facilities than others. We may have more centralized kitchens than others. So I can’t say that there’s an overall general plan as much as I can, that we have to be very, very clever and smart on how we work at the local level, what are the different disasters that are facing us, and how do we work with the existing partnerships and the assets that exist within those communities. It’s not going to go away. And the national expectation, as I said, for The Salvation Army is very high. They expect us to be there.

Christin Thieme: It seems like many of the disasters that we see disproportionately affect low-income communities. How do you think The Salvation Army specifically addresses the needs of communities in the aftermath of a disaster, maybe uniquely? And is there an example in recent memory that perhaps you could give?

John Berglund: There’s many. So the unemployed, the working poor, the marginalized, our clientele that we work with on a daily basis. They are always the most at risk in a disaster situation, the undocumented as well. The advantage is that we work with these communities on a daily basis. And when it comes to disaster scenarios, I think it’s always best for to say, okay, how do we in essence take care of our own? How do we take care of the clients that we work with on a daily basis? Because yes, they will be the most vulnerable in these situations, whether it’s for feeding, financial assistance, sheltering, whatever. So we do what we continue to do. We know these populations, we work with these populations. And when we go into these scenarios, I think it’s best for us to say, hey, the unhoused in those urban communities, we work with them every day. We know how to work with them. We know those communities. Let us come up with programs and work with them, both in the response and recovery. I think that’s the perfect lane for us. That’s where we are most of the time. Now, an example, you may have in a recovery program, we may look at one where we say, okay, look, let’s focus on seniors. Let’s focus on seniors and just look at programs on how to address the needs of seniors and meet their needs. Often, I’ve been in situations where the Army said, okay, for disaster recovery centers, you have to have documentation to get in the door. I’ve seen the Army set up its own response centers where no questions asked, we’ll help however we can.

Christin Thieme: The psychological impact of disasters is something that sometimes gets overlooked in the response. We see the feeding and the housing and those physical needs that are being met, but that psychological impact is so important. And The Salvation Army has always had its emotional and spiritual support side for survivors and first responders. Why do you think that element of our response efforts is something that’s remained a core part of what we do for so long and why will it continue to be there?

John Berglund: Yeah, it is a core part and it will continue to be there. In all catastrophic incidents, whether it’s personal just affecting one family or whether it affects an entire community, there’s going to be post-traumatic stress, which is a normal reaction to an abnormal event. And that will go on for quite some time.

I think the Army is known for its emotional and spiritual care and its wisdom when it comes to ministry of presence and how to address the needs of these people, these folks. Psychosocial support is huge, not only for the individual, but also for the community. So there’s a lot of ways it’s going to continue. There’s no doubt about it. And I’d say it’s one of our strengths. It also requires training. It does require training. To be a pastor is one thing. To be a pastor that understands DMORT or mortuary service for disasters or to be there with the ministry of presence and know how to recognize the signs of post-traumatic stress and how to deal with them. I think that’s key. So it’s inherent in our culture. It’s inherent in our DNA, which I think is all good. At the same time, we have to continue to train our people on the differences between normal pastoring and coming alongside those who ask for it and addressing the direct needs of a major impact of a catastrophic incident.

Christin Thieme: And it goes beyond that immediate relief as well. I mean, outside of that first initial response in the aftermath of a disaster, The Salvation Army is often engaged in more long-term recovery efforts. Is there an example you can think of in the past year or two of The Salvation Army supporting a more long-term recovery effort in a particular community?

John Berglund: Let me address the most recent, which was the Lahaina fires on Maui. So the Lahaina fires, The Salvation Army there was the lead agency for mass feeding for the state of Hawaii. So we had a major role for a good six months in that response phase of feeding, feeding in multiple locations, as well as having a presence in the Disaster Service Center to provide support into intake for survivors. Now, the recovery program for Lahaina will go on for years, several years, you still have five, 6,000 people that are being sheltered, you still lack jobs, you still lack housing. So the Army, because we’ve been in Maui since the 1800s on Hawaii, we’re not going anywhere. There’s no exit plan. And the beauty of the Army, I think, is that it’s patient. It will wait and see what resources are coming down the pike for the survivors. And then we’ll look at the gaps. What are the gaps? I mean, in some ways, as always in social services, The Salvation Army is the last safety net.

So often what I’ve seen in disasters is when a lot of these other agencies roll out or their funding drives up, the response is always the same. Oh, you still need help with this, or you still need help with the kids, you still need help with appliances, go to The Salvation Army. So often as things go down and we go into a recovery phase and the news agency’s going away, it’s usually the local corps who picks up those pieces and continues to be a resource on a local level to help meet needs for recovery. And as I said, the Maui example, we have a recovery project coordinator, we’re involved with the community on the long-term recovery group, we chair the unmet needs committee, so we’re heavily involved in that community because we’re a part of that community, and it’s not going to end anytime soon.

Christin Thieme: And like you said, that response will continue for years and will still be there ongoing. Being so entrenched in this world, what’s a common myth or misconception that you encounter a lot when it comes to disaster relief?

John Berglund: You know, for years, I used to hear, well, there’s been no disaster in that community for two years, so why do you need EDS personnel? I think the biggest myth and misunderstanding is that disaster response in the United States is a billion dollar industry. It’s a well-oiled machine. It’s very competitive. And what we’re doing in blue skies when there’s not an event. What we’re doing is we’re forming relationships, we’re planning, we’re working with the state, we’re getting written into state feeding plans, emotional and spiritual care plans. So there’s a lot of legwork that goes on before an incident happens. And that’s the piece. If you miss that piece, it’s very, very different when something happens immediately and we don’t know what our role is, we don’t know what our place is. It’s much more difficult. So the industry has changed. The industry has changed. I think the roles of divisional EDS directors have changed both with contracting, both with technology and working the community relationships. It’s 365 days a year.

Christin Thieme: What about on the individual level? What would you recommend to somebody, maybe to their family, for the changing disaster landscape? How should individuals be thinking about preparing for disaster?

John Berglund: Maybe the first is to know where do you live and what are the hazards? What are the hazards that can potentially affect your community and protect your family? And then there’s lots of material both on Salvation Army websites and across the country on how do you prepare as an individual and for a family? How do you keep supplies for when the power is gonna go out for two to three weeks? How do you keep a cash reserve? How do you know? If something immediately happens, where do all the family members meet up? So there’s lots of material out there, like I said, on Salvation Army websites on how to prepare. And you want to prepare, because like I said, once the incident happens, it’s very difficult to reach for help in some situations or to know what to do. So you have to take this stuff seriously.

Christin Thieme: Do you keep supplies at home?

John Berglund: I do as much as I can but even still you know it’s like the contractors that don’t work on their own homes. We miss these things unfortunately but they’re very very important.

Christin Thieme: It’s one of those things that’s always on the to-do list, but you need to actually do it. So then what’s the best way for somebody listening to get involved in supporting what The Salvation Army does in disaster relief? How would you recommend they get involved?

John Berglund: We get a lot of inquiries on a national level and on a regional level where folks want to get involved with disaster service. We always give the same answer, it’s like, look, you need to plug into your local Salvation Army. Just look up your local corps or the different facilities that exist in your community. Make those relationships, volunteer with those efforts, and then you will be able to secure EDS training. But if you’re gonna be a spontaneous volunteer, that is true as well, on where is the Army locally? How can I get involved? If you wanted to be an affiliated or trained volunteer, that’s possible as well. But I would start at the local level. I would start at the corps level. Contact your local Corps and ask about disaster services and see how you can get involved. They may not have an incident every week, but the point is you need to make relationships with the Corps officer and with their staff. And if you want to be part of that group, that’s where you start.

Christin Thieme: And here in the West, if you just head to WesternUSA.SalvationArmy.org, you can plug in your zip code and get all the information on where your local Salvation Army facility location is right nearest you. So that’d be the first place to start. And you can also find more information there about how you can get involved in giving to help these efforts and just kind of getting everything ready to go, like you said, while there’s blue skies and being ready for whatever might come, hopefully not, but just in case.

Well, John, thank you so much for sharing today. What would be your last word of advice for anybody listening when it comes to disaster relief, disaster response, and preparedness?

John Berglund: Well, I think as you said, the first thing is to be prepared both individually and for your family and once those boxes are checked then I think you can start looking at how do you help within the community and how do you come along aside The Salvation Army to help. But start with the individual, start with the family and then reach out and contact us to get involved.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.