“There is a growing awareness of the impact of inequality…Young artists are connected to social movements or to their ideologies through social media, and this will inevitably affect their interests and their work.” – Suzanne Lacy

A new wave of artists are making change happen.

Ninety-nine years ago, Marchel Duchamp kicked up a major fuss by taking ordinary objects—a snow shovel, a urinal, a bike wheel—and reframing them as art. Nearly a century later, a growing movement once again is looking to radically reimagine the relationship between aesthetic experiences and everyday life: social practice art.

Ninety-nine years ago, Marchel Duchamp kicked up a major fuss by taking ordinary objects—a snow shovel, a urinal, a bike wheel—and reframing them as art. Nearly a century later, a growing movement once again is looking to radically reimagine the relationship between aesthetic experiences and everyday life: social practice art.

Unlike Duchamp’s revolutionary readymades, which spun an object with a purpose into something purely symbolic, this art form is purely pragmatic, and for the most part, it lives happily outside institutional walls. There is no brush stroke or bronze. There’s no stanchion on the sidewalk to direct ticket holders into an orderly herd. And there’s no need to appease curatorial gatekeepers because gaining entry is almost beside the point.

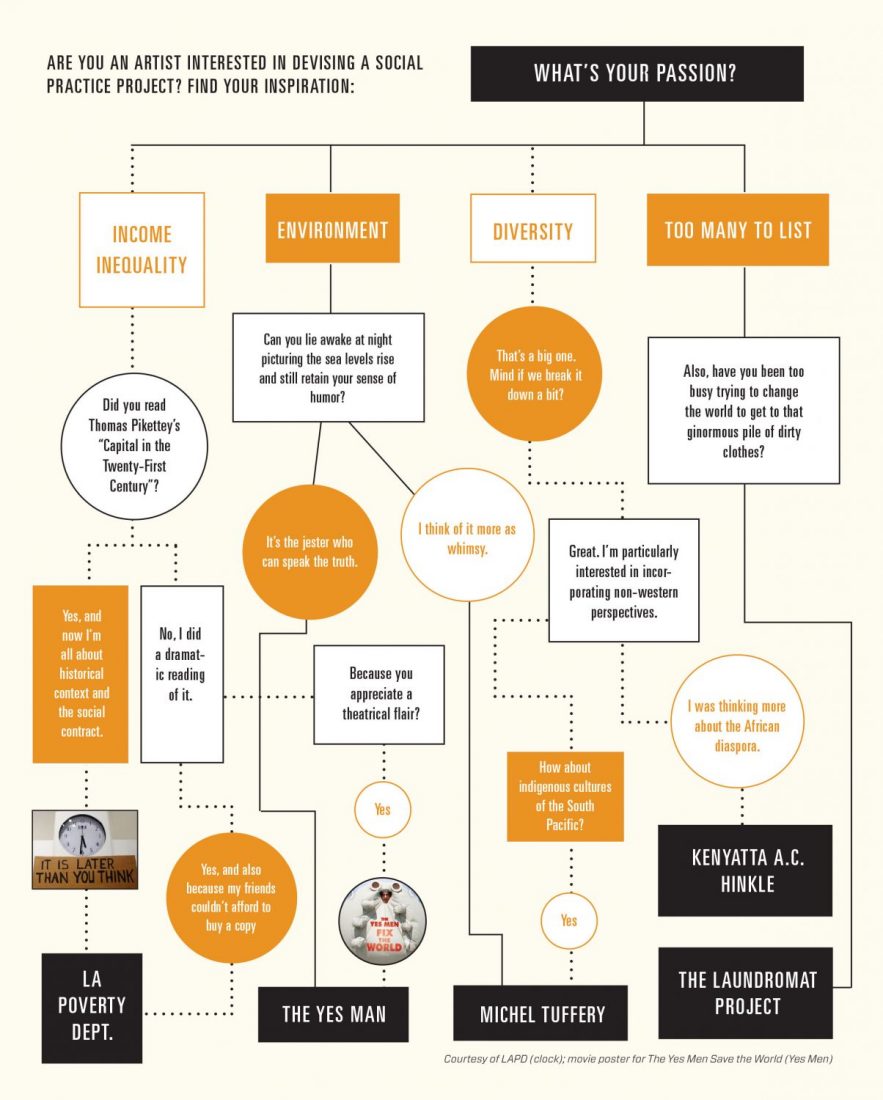

For this generation, making art is about making change. Art is what art does.

In the past, activist artists employed their creativity to signal a problem. Now, social practice artists are devising creative approaches in an effort to actually fix things. And they are starting with the belief that in order to change lives, you have to harness the imagination and experience of those whose lives you are hoping to change—in collaboration with them, in their neighborhoods, in their streets, even in their homes.

The term social practice hadn’t yet been coined. No road had been mapped. So Lowe did what groundbreakers do: he made it up as he went along. He brought in a mix of artists, local residents, church groups, architects and urban planners, and together they transformed the shacks into Project Row Houses, a unique hybrid of arts space and social service center.

Lowe credits a high school student for sparking the idea. “He looked at my earlier political work [billboards], and he basically said it wasn’t what people needed. People needed solutions,” Lowe said in an interview when he won the MacArthur genius grant in 2014. “If you’re an artist and you’re creative,” Lowe said the teen asked him, “why can’t you create a solution?”

“Rick saw what people believed to be the most dangerous block in Houston, and he saw it as an opportunity for how to use his talent to transform a neighborhood. Art was a catalyst to serve needs of community,” said Eureka Gilkey, executive director of Project Row Houses, which now takes up 10 blocks and 49 buildings. They house a vast array of programs—from artists’ residencies to tutoring for children, from public art gallery space to subsidized housing and mentorship for single mothers.

Today, the Third Ward is thriving and Lowe is lauded as a forefather of social practice.

Over the past 10 years, the movement has been gaining traction in academia. At least 10 schools, including Queens College, Otis School of Art and Design and Portland State University have established master’s programs in social practice art and young artists are flocking to them. “The social conditions in the country are ripe for social change. We see that in the elections now, with the strong showing for candidates from both ends of the political spectrum,” said Suzanne Lacy, department chair of Otis’ Public Practice graduate program. “There is a growing awareness of the impact of inequality…Young artists are connected to social movements or to their ideologies through social media, and this will inevitably affect their interests and their work.”

That same socially conscious mentality is sweeping through museums, leading them to experiment with new ways to engage audiences—sometimes by looking beyond their own walls.

The Queens Museum is considered a leader in the field. Five years ago, the Museum embedded Cuban artist Tania Bruguera in a storefront on Roosevelt Avenue in Corona, Queens, where she created Immigrant Movement International, a community space where art and education are used to empower immigrants personally and politically. The space hosts everything from computer and zumba classes to legal services and political protests.

In 2013, the Tate Modern exhibited Suzanne Lacy’s The Crystal Quilt. Lacy is a pioneering performance artist who has been blurring lines between art and activism since the 1970s. She created The Crystal Quilt over two years in Minneapolis in the 80s to explore how aging women are represented in media and public opinion. The project culminated in a large-scale performance installation in a shopping complex with 430 Minnesota women over age 60 seated on a rug designed by painter Miriam Shapiro to resemble a quilt. The Tate acquired and exhibited representations of the quilts alongside photographs and a video documenting the live work.

While some social practice artists do see their work find its way to such hallowed halls of museums, others see no need.

Inspired by her personal experience as the daughter of a Korean immigrant and a Jewish New Yorker—raised on one grandmother’s denjang-guk and the other’s matzoh ball soup—artist Lisa Gross hit on an idea that would unfold in the kitchens of Queens.

Two years ago, she launched League of Kitchens, a cross-cultural exchange achieved through cooking and sharing food. Gross recruited and trained women from a wide variety of backgrounds—from Argentinian to Uzbek and everything in between—to lead workshops for the public in their homes.

“It’s about recognizing the richness immigrants bring to our culture and society and elevates the experience of these women in a public way,” Gross said. Which is one of the reasons League of Kitchens has made a point of making it into the mainstream media. (This past January Stephen Colbert clowned his way through an “Indian Cooking with Yamini” workshop on The Late Show.)

By recognizing the women for their cultural and culinary expertise through paid, meaningful work, League of Kitchens is an empowering flip of the script. So often, Gross notes, the intersection between immigrants and non-immigrants is a service-based experience—they work at dry cleaners or as dishwashers. “Here, the immigrant is the expert, the host, the teacher,” she said, “They are the one in control. They’re the person in power.”

Nobody doubts that empowering the disenfranchised is a laudable endeavor, but some critics wonder where aesthetics come in. Simply put: is an Uzbek cooking class a work of art?

“As an artist I can take inspiration from both worlds—activism and art—and any world, and make something interesting and meaningful,” Gross said. “As an artist you can be inspired by anyone and anything and make something new and you don’t have to feel confined.”

Art, she argues is about expanding ideas and definitions—especially within the world of art. “The art world can be rigid and conventional,” Gross said. “I reach a diverse and wider range of people beyond who would typically engage in performance art or public art.”

“I think that aesthetics and politics and organization success go hand in hand in a social practice project,” Lacy said. “For instance, I might consider something more successful on one or the other of these bandwidths. In the case of aesthetics, these are determined by the disciplines, for instance, of installation or performance or video. In the case of politics, the accomplishment of a project might be to hone a theory or analysis, or reveal connections between systems. But on an organizing level, we would consider the impact of the project on people, the scope and size of the engagement, and possibly the ‘results.’”

Ultimately, Gross addresses the issue in a way that many in her generation would likely relate to: she dismisses it. “In some ways, I left behind the art world. I think and work like an artist, but whether what I do is good art or not? I’m not interested in that question. Have I created a meaningful experience? That’s what I care about.”