When the streets are all you have, Los Angeles’s Bell Shelter offers embrace

Alexandra Tostes opened her eyes one morning on the couch of a Hollywood drug dealer and began her usual routine–a few drinks of alcohol and a line of meth. But that day it was different; she could feel all the pain, shame and remorse that she had numbered for 14 years with drugs. She lived as a transient since leaving home at 16, doing errands and cleaning for various dealers in exchange for leftover drugs and a couch to sleep on.

As a child, a serious car accident left Tostes’s mother in a coma; the accident altered the course of their loves. Tostes was moved to a foster home for a year while her mother rehabilitated. When she returned, expecting to be reunited with her mother, Tostes said the once familiar instead seemed like a complete stranger; she no longer offered a warm embrace. Instead of dealing with the pain of isolation, Tostes said she turned to drugs to help forget feeling alone.

That morning, lying on the sofa, Tostes knew she had to find treatment. she found a Yellow Pages directory in the dealer’s apartment and started calling programs.

“I kept saying, ‘I need help,'” Tostes said. “They would all ask, ‘Do you have insurance? No. ‘Do you have money?’ No. ‘Do you have ID?’ No. They basically said, ‘sorry we can’t help you.’ I was close to giving up.”

She resolved to try a couple more times and dialed a number for The Salvation Army.

“I said, ‘Look, I’ve been calling programs all day. I know what you’re going to ask and I can tell you straight off I don’t have ID, I don’t have money, I don’t have anything. The only thing I have is me,” Tostes said. “The voice on the other end said, ‘All we need is for you to stop using. What time can you be here?’ It was the best thing I’d ever heard.

“They embraced me and made me feel loved. Slowly but surely, I started feeling all the things that I was chasing–the love, the caring, the nurturing, the encouragement–the things that I didn’t have while I was using.”

Ten years later, Tostes still walks the halls at Bell Shelter; she is the associated executive director.

“I knew then,” she said,” It was like God tapping me on the shoulder and saying ‘You’re home.'”

Converting a warehouse

The Salvation Army Bell Shelter today houses 450 a night, plus an additional 70 during winter months, in a converted 40,000 sq. ft. hangar, formerly a U.S. Army Air Base in a secluded industrial area in the city of Bell, roughly six miles southeast of Los Angeles.

The building was renovated in the early 2000s with $3.9 million from the County of Los Angeles Department of Mental Health.

The warehouses located at the Bell Federal Servace Center were built in 1943 to store supplies waiting shipment to troops in the Pacific theater of WWII. The shelter opened in January 1988 in 3,000 sq. ft. of extra space–the first site to be utilized under the Stewart B. MicKinney Homeless Assistance Act–because of the vision of Judge Harry Pregerson.

“Any issue that involves human suffering, depravation and degradation is important to me, wherever it occurs,” Pregerson said. “I can do my part to alleviate, for example, the surge of homelessness. That’s one of my missions in life.”

Pregerson, 85, is a judge on the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, appointed in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter.

AS he drove to the federal court house in Los Angeles one winter day in the mid 1980s, Pregerson heard a story on the radio reporting that then Mayor Tom Bradley had opened the City Council chambers to allow homeless people to sleep inside instead of out in the bitter cold. Several homeless people had died of hypothermia during an unusually cold winter in L.A. The idea became Pregerson’s passion.

He attempted to also open the doors where he worked, in the federal courthouse, to allow people to sleep in the lobby. Pregerson acquired cots and blankets from a local Army/Navy armory, but met strong opposition from some people in the building.

Frustrated with the response, Pregerson then received a call from a U.S. Marshal and Marine reservist about possible space at a federal supply center in Bell. Pregerson investigated the following day with Louise Oliver, then an official of the General Services Administration, and then Congressman Edward Roybal.

With 3,000 feet of warehouse space, cots and blankets, Pregerson had to find someone to operate the shelter. He called various organizations without success until, while watching TV one day, Pregerson saw then Divisional Commander Lt. Col. David Riley talking about The Salvation Army. He called Riley the next morning.

“I said, ‘ Well, what do you think, Colonel?'” Pregerson recalled. “And he replied, ‘It’s perfect.'”

Pregerson also made a call to his brother-in-law, real estate developer Guilford Glazer, who donated $50,000 to cover the initial operating costs.

With some loaned vans, Pregerson, Riley and dedicated people including then Captain Dave Hudson, then Captain Donald Bell, and Russell Prince would pick up homeless people from East Los Angeles, Hollywood, Long Beach and Pasadena and bring them to the shelter for a warm place to sleep, soup and bread at night, and doughnuts and coffee in the morning.

“It has greatly expanded now; I wasn’t thinking then about computer literacy, a library or gym,” Pregerson said. “My initial idea was to get people off the streets so they didn’t die. But the more you get into this kind of thing, the more you become aware of the need and do whatever you can to take care of it.”

He said, “Nothing gives me morel lea sure than to go there and chat with people; I feel like I’m at home.”

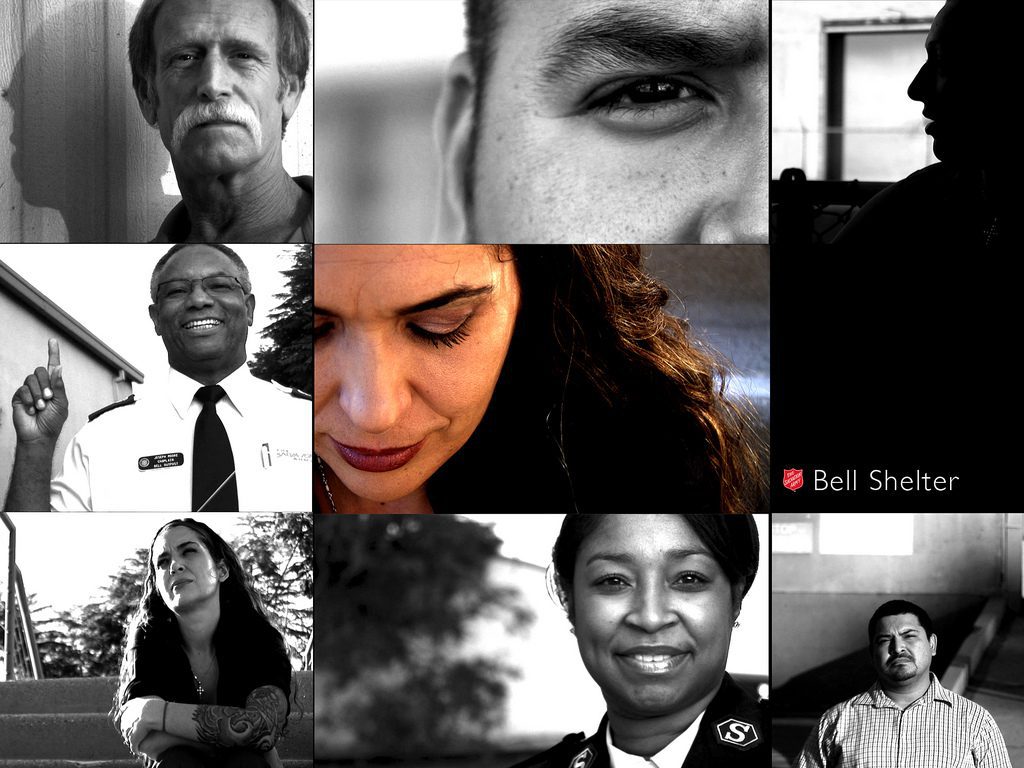

A family of strangers

Besides a bed and three meals, homeless clients at Bell Shelter today–including those requiring medical attention, the unemployed and veterans–receive comprehensive transitional care to help them reintegrate successfully and self-sufficiently back into society.

The network of beds, classrooms and cafeteria houses a community of strangers with strained pasts. But in this society of seeming failure, these residents are united by hope–for a better life and better future. They hope this for themselves, and they love and support their new family along the way.

The residents must adhere to an array of schedules, obligations and incentives under one common 40-foot ceiling. Many are desperate to change; the desperation breeds success.

The shelter operates on an annual budget of $4.3 million. Most of the money (75 percent) comes from federal and state funding; the shelter must raise the remaining 25 percent.

“Our roles is to address the issue of homelessness strategically through coordinated care and coordinated response, so that reintegration happens through employment, a healthy lifestyle and productive community involvement,” said Major Victor Leslie, divisional commander for The salvation Army in Southern California. “Bell sHelter’s ultimate goal of putting the client on the road to achieving self-sufficiency and independent housing represents a model aimed at shifting from managing homelessness to ending it.”

Street sleeping by the numbers

The amount of homeless people is staggering. On any given night in Los Angeles County, 73,702 people are without a home, according to Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) data from 2007. LAHSA conducts a massive count of homeless individuals with over a thousand volunteers every two years. The next count will take place January 27-29, 2009.

Of that number, 40,144 individuals are on the streets of the city of Los Angeles.

“When you’re on the outside looking in, you really don’t realize how big of a problem it is,” said La Rae C. Neal, executive director at Bell Shelter. Neal spent most of her career in the business sector but wanted a change after her sons left for college. Once she stepped inside Bell Shelter, she said she knew she wanted to be part of it. “Many of us can be one day away from homelessness; none of us are above the issue.”

LAHSA also recorded general demographics for the homeless population: 83 percent are unsheltered; 59 percent are men; 12 percent are veterans; 33 percent are chronically homeless; and the median age is 45.

“People can come here and feel like they’re home; you don’t come here and stay for a few days and then go back on the street. If it takes you a year, if it takes you two years, you can stay here until you get your life back together,” Neal said. “I don’t believe we would be so successful today if we were relying on man or money. It is ah higher power that is keeping us going.”

Facets of a shelter

Bell Shelter houses clients in five separate classifications.

First, the 128-bed Wellness Center is a state licensed drug and alcohol rehabilitation program. The majority of beds are paid for by government entities, while 25 beds are self-paid at $550 per month (though the actual cost is $1,027). Depending on individual length of recovery, clients can stay here for up to a year before transitioning into the shelter.

SEcond, the main shelter has 135 beds. Clients in this stage are allowed more privacy and freedom than in the Wellness Center. Two people share a cubicle with two twin beds in a room full of cubicles, called the “clusters,” that are separate for men and women. Each day begins with breakfast–to be eaten by 7 a.m.–and then classes or work until the evening. Clients meet weekly with a case manager to establish and follow a personal plan for success. while in this phase, clients contribute 30 percent of any income they have and save the remaining amount.

Once a client has secured a job and worked for three months, he/she is eligible to move onto the transitional living phase at Bell Shelter. Here, 56 clients live in trailers across from the main shelter. They work, make their own meals, arrange their own transportation, pay a minimal rent, and meet weekly with a case manager to focus on finding permanent housing once their one-year trailer stay is over.

In a separate building, Bell Shelter has a 70-bed emergency shelter that is open from 2 p.m. to 8 a.m. daily. Another 70 beds are added during the winter months. L.A. County contributed $500,000 in 2006 to allow clients to remain here for up to a year while paying nothing. The goal ifs or them to find a job during their stay, work and save all of their income. Many move into the main shelter after a year.

Funding is set to expire for the emergency shelter in 2009.

Finally, the John Wesley Community Health Institute provides medical care in the Recuperative Care Center at Bell Shelter. Resembling a hospital wing, 30 homeless patients that are too well to be in a hospital but too sick to return to the streets can receive medical care here 24 hours a day. Once healthy, meany of these clients then transfer into the Wellness Center or the main shelter.

Finding answers within

According to LAHSA, 74 percent of homeless people in Los Angeles experience a disabling condition, such as mental illness, depression, physical disability or alcohol/drug abuse.

Psychotherapist Paul Wager has counseled clients at Bell Shelter for almost five years in addition to the onsite mental health clinic in collaboration with the East Los Angeles Mental Health Clinic. The clinic provides caseworkers, assessment, a psychiatrist once a week, prescriptions if necessary, therapy and groups. The meetings include topics such as 12 step, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, self-esteem, conflict resolution, money management, motivation, communication, and hygiene.

“Every client has a different story and different needs,” Wager said. “The homeless population is very diverse; they come from all walks of life and socio-economic groups.”

Wager said that when most clients arrive they are experiencing situational depression and anxiety.

“Therapy is a process of helping clients figure out what their truths and goals are,” Wager said. “I try to help them find answers within themselves so they can turn that truth into reality.”

while Wager said some shelters only offer “three hots and a cot,” referring to meals and a bed, “Bell Shelter offers a comprehensive program to promote an overall level of functioning.”

Preparing for a new life

The emphasis at Bell Shelter is on achieving self-sufficiency, which often requires education and job training.

The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) provides classes in computer literacy, English (for second language learners)m and General Educational Development (GED) to certify that the individual has American high school-level academic skills. Roughly one client per month receives a GED certificate at Bell Shelter, which requires a test score higher than 40 percent of graduating high school seniors nationwide.

Dolphin truck driving school sends representatives to Bell Shelter to run a 10-week driving school, which earns clients a Class A drivers license and a job offer. Sergeant Lane Bragg from the Los Angleles Police Department teaches security guard certification classes. The LAUSD also teaches computer repair technician classes. with a donated $77,000 pizza oven from California Pizza Kitchen, Bell Shelter just began offering pizza certification classes.

Bell Shelter also hires many of its own–38 of the 88 current employees and 16 of the 22 current case managers are former clients.

“Ask any of the numerous employees at Bell who were once homeless, drug abusers or lacked mental health counseling how valuable the work is at Bell Shelter and the testimonies of salvation, reunited families, job stability, increased hope, improved health and overall crossing over to a new life would blow you away,” Leslie said.

To care for their personal needs, clients also have access to a wide array of facilities including three free onside Laundromats; a full gym, with equipment donated by Kenny Rogers; a stocked library and reading room; a salon, where volunteer beauty school students provide hair cuts and styling; and twice a week, Los Angeles’s Dream Center brings a medical van to provide care to residents.

“Bell Shelter is a place of extreme makeover, a place where so many have an opportunity to, ‘ring out the old, ring in the new, ring out the false, ring in the true, ring out the grief that saps the mind, ring in redress to all mankind [Alfred Tennyson],” Leslie said. “Above all, they become new creations in Christ.”

An invitation home

Bell Shelter boasts a 90 percent success rate for clients who enter and graduate. Of these clients, 76 percent remain self-sufficient, monitored by case angers who contact graduates to offer encouragement every three months during they first ear back in society.

And then there are those who turn their tragic life stories into incredible triumph–people like Alexandra Tostes.

“It feels great to be in the position where I can make a difference, because The Salvation Army made every single difference in my life,” Tostes said. “The clients’ stories keep me sane and grounded. The thought still comes in my head, even after 10 years, that a drink would be nice. But when they share their experiences from a day ago, it keeps my awareness up that the pain is still out there if I want it–but I don’t want it anymore. tHeir pain is so fresh it keeps me grounded. I share my experiences to let them know there is hope, but they are helping me just as much as I am helping the,”

A large glass vase sits on a shelf above her desk overflowing with thank you cards from past clients and people she has impacted. Tostes said she reads them when needing a reminder of what she has overcome.

Now when Tostes sees an addict living on the streets–an experience she well remembers–she stops and asks if they want help; she asks if they’re tired of living that way.

“I can relate,” she says, and hands over a business card–evidence of a transformed life.

Tostes offers a simple solution, “Come home to the Bell Shelter if your’e ready to find hope.”