This season, we’re discovering The Salvation Army’s Pathway of Hope—a national initiative to provide individualized services to families with children, addressing their immediate material needs and providing long-term engagement to stop the cycle of poverty.

Last week, we heard from a smalltown service center director about what it takes to deliver Pathway of Hope support day-to-day along with a current participant in the initiative.

But let’s take a step back. We’re delving into the Pathway of Hope this season, but what is hope?

Kierkegaard called it a passion for the possible.

Psychologist C.R. Snyder said it’s a reservoir of determination.

Emily Dickinson said it’s the thing with feathers that perches in the soul and sings the tunes without the words.

It’s hope.

As Desmond Tutu said, it’s being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness.

And it’s an essential ingredient, part of the namesake of The Salvation Army’s Pathway of Hope.

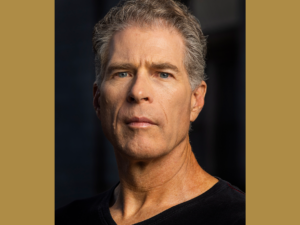

Dr. Suzanne Phillips is a licensed Psychologist, Psychoanalyst, and Fellow and Co-chair of Community Outreach for the American Group Psychotherapy Association (AGPA). She has been a psychologist for more than 35 years and is a newly retired Adjunct Full Professor of Clinical Psychology at LIU Post, a private university in New York.

She’s long provided services and trained others on trauma response and disaster—from earthquakes, to school shootings and 9/11. She’s testified before Congress for the needs of military members and their families—and runs a camp on resiliency for military children.

She is the co-author of three books and host of “ Psych Up Live” an international talk radio show on the Variety Channel of VoiceAmerica.

And as someone in the business of hope, she’s on the show today to help us better understand hope and what it does psychologically and physiologically—plus how we can recognize it and find more of it in our lives.

It’s not magic, she says, but a mindset, a propeller for action and possibility. And, it’s contagious.

Show highlights include:

- Is hope the same as optimism.

- What a hopeful person looks and sounds like.

- How Dr. Phillips has used hope in her life.

- How does hope change us psychologically in order to make a difference in our lives?

- More about a study that recognized people trapped in a cycle of poverty suffer despair, low self-esteem, and hopelessness and what it found.

- The difference hope can make in our bodies.

- Common barriers or obstacles to hope.

- Components of hope and how we gain it—especially for those in extremely challenging, painful circumstances?

- If there’s a danger in hoping for what’s possible instead of focusing on what’s probable.

- What must be considered when you’re approaching hope as part of a program to impact people’s lives for good.

- How to improve your hope today.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: Dr. Phillips, welcome to the Do Gooders Podcast and thank you so much for being here with us today.

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Hello, thank you for inviting me.

Christin Thieme: Can I ask you to start: What is hope? And is it the same as optimism?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Okay. So for me, hope is the belief in options in the future, Christin. It’s action-oriented. Hope is not a lack of fear. It’s not a lack of pain. Hope is being able to see that there’s light despite the darkness. Now, if we talk about optimism, someone might say, “I’m optimistic that the country is going to be okay.” Hope is different. Hope is the belief that if we try to bring people together, or if we try something like Pathway of Hope, your program, there’s a chance we might help people out of poverty. That is hope. It doesn’t assume it’s all going to be okay. Hope is an action-oriented belief system. Charles Snyder calls it something that’s fueled by two pathways. Well, the idea of believing that something can happen and finding pathways to make that happen, it’s willpower and way power. Hmm.

Christin Thieme: So is it something that you can recognize in somebody? What if somebody is full of hope? What would that look like or sound like?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: In my work over all the years, over 35 years being a psychologist, someone with hope believes that they’re going to give it a try. And even if there’s a 1% chance and something happening with respect to their health, or with respect to someone in their life, they’re going to believe in that. And they’re also going to work to make that happen. So an example would be in Grossman’s book about hope and the power of hoping, healing with medicine. One of the doctors who was a specialist in stomach cancer, and he worked worldwide, he ends up being diagnosed with it and he chooses a very, very extreme approach to address it. And the young doctors think, oh my gosh, is he suicidal? This is really so radical. He’s in ICU. Why did he choose this particular protocol? First of all, we, 20 years later, someone meets him for lunch and says, we wondered what you were thinking. We wondered if you were suicidal. And he said, my position with myself and my patients is that if there’s a 1% chance, I’m going to give that chance because there I’m going to rest easy that I gave it my all.

So I think a person with hope keeps trying and they keep using action to make life better. And when the plan doesn’t work, they use the information they got from what happened that didn’t work to re-set up a plan. It’s the plan to change the plan, but it’s always the belief that there’s a possibility in the future.

Christin Thieme: So it is partially state of mind, but then also being willing to take that action consistently. Is that right?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Yes. And what fuels hope most of all is connection. I truly believe when someone feels someone believes in them they’re more likely to be able to hold on to hope and keep trying.

Christin Thieme: How have you used hope in your life?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Well, I will say that I think I’m in the business of holding hope for people very often because I will literally say I’m going to believe in you, even though I know it’s very hard for you to see yourself out of this depression or see yourself through this grieving, but I know you, and I know you have the wisdom of a survivor, sometimes in terms of holding onto hope for people. And we said, when someone’s suicidal, Christin, their thinking is very, very compromised. They can’t remember when they’ve ever gotten out of a bad situation. They can’t see the possibility of a change at that point. It’s so narrow, the thinking. They only feel that this is intolerable inescapable and interminable. And if you’re in a position to help them consider that 10 moments from now, this may feel different. If we try something, we are going to find out, it’s not interminable, that the thinking has made them able to see in the tunnel.

Some people who work with suicide hotline say their job, Christin, is building windows in that tunnel, allowing some light to come in. So in terms of my work, I feel like I’ve been—I do a lot of trauma and outreach work. I feel like I’m very much in the business of hope in my own life. In terms of family, at one point, one of my sons was in a near-fatal car accident. I think we held on to hope. I think his brother really fueled it. And we kept trying to remember that even as a child, he did incredible things. He would run major races at five years old. He was very, very gifted. So we kept believing in the possibility of him beating all the odds, which he did, thank goodness.

Christin Thieme: From your work and from your experience, how does hope change us psychologically?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: It really opens up the space to allow us, instead of thinking in a depressed way or in a way in which we have no choices, to believe that something different can happen. So if somebody is given an opportunity to try something—as your program and in the program that Nicholas Kristof talks about, the graduation program—it allows people to graduate out of poverty because it allows them to believe someone cares. That changes the thinking. “They’ve just given me livestock, and maybe that means I can make a little bit of money from it.” So all of a sudden there’s a mindset of possibility and well, maybe we’re going to talk about this. What we found is that people began taking jobs beyond the particular gift they had gotten in terms of livestock or bees or whatever it happens to be. So what hope does is give people resilience.

There’s a very close tie in with resilience and being able to go the course, even though there’s roadblocks, even though there’s storms, the belief that there’s options and that you can find a pathway fuels resilience and resilience fuels hope.

When we had our military capturing, I remember the Hanoi hotel in Vietnam. I mean the chances of them getting out were not probable, but it became possible because of a code of communication they developed between each other, banging on pipes. And the hope of one person is contagious to other people. So it’s very much a mindset that fuels the best of us and the best of us together.

Christin Thieme: I love that. You wrote an article about hope for Psychology Today, and you referenced a study that recognized people trapped in a cycle of poverty suffer despair, low self-esteem and hopelessness. Can you share more about that study and what it found in relation to hope?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Yes. I just made reference to it, but I’ll expand. So that was the graduation study and we had 21,000 people in it from India, Ethiopia, many undeveloped countries. And when we think of what they were giving them, it wasn’t really much, but it was enough. It was enough magic to stir hope. So they would give people a cow or they would give them chickens, or they would give them a beehive. And they also gave them, Christin, either a supply of food or some money so that they would not sell this potential sort of represented by the livestock or the bee or the chicken. And what happened is they also gave them, they developed a savings account for them. And what they saw happen was over the course of the years that they ran this, it was a 400% improvement in the conditions of these people’s lives.

And they thought, how could this possibly be? But what happened is when you give people the ingredients to actually have a sense of agency, meaning I can do something that could help my own poverty—and as you said, not only economic but poverty of spirit, poverty of self-esteem, poverty of a despair of not being able to feed your children—when you give someone something that gives them agency, it expands. So even though they didn’t tell people to do this, people began to find other ways to make money in the ways to bring in income. So the one gift of agency, the one gift of hope really expanded. And so the results, when they looked at it, they said it can’t just be the things we gave them. It has to be the power of hope.

Christin Thieme: That’s amazing. So it’s this mindset of possibility, which really can change things for a person. What about physiologically—can hope make a difference in our physical bodies?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Well, what I love about Groopman’s book, which is “The Anatomy of Hope: How People Prevail in the Face of Illness,” and there’s another book called “The Magic Feather Effect: The Science of Alternative Medicine and the Surprising Power of Belief” [by Melanie Warner]. And that comes from the movie “Dumbo.” I think it’s a crow who says to the little elephant, “I’m going to give you a magic feather, and that’s how you’re going to fly.” And of course, he flies and the person who wrote this book, she checks out many, many different types of holistic approaches. And many of them really can’t find exact concrete, gold, random study evidence. But what we know is that when people are hopeful, when they believe in something that really results in the release of hormones, feel-good hormones. So that it’s the opposite of the cortisol that you would be releasing if you found stress, you know, it’s the endorphins. And so one of the things we know about hope, which is a belief system, is the power of it to literally change someone’s physiology.

So that, I think when you talk about inviting someone to believe that speaking to someone on a phone is going to make them feel better or reduce their pain, the fact is it usually does when they asked people, what was it about the particular treatment they got? They would say, well, I believe in this person, I have always gone to her. She has always helped me with acupuncture. They even interviewed the chaplain and they said, how do you explain the fact that people end up leaving here, feeling there was a miracle in terms of their physical wellbeing? And he said, I think it has to do with belief systems, because we don’t have the, as I say, the concrete data in terms of physiology, but we do see that people improve. So there’s definitely a tie in with physiology and psychology when it comes to hope.

Christin Thieme: So we know hope works. What do you see are the most common barriers or obstacles that people face in being able to access or have this mindset, this hope?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: What are the hardest things? And I think the biggest obstacle can be isolation, Christin. They say no one’s more hopeless than a person with a problem they feel they cannot solve. And thankfully, when we think of what we went through with COVID, thank God people were able to contact senior citizens and speak to them. Someone that I know was a contact tracer and what her real job was to give hope to senior citizens, because often once that she connected with them, they said, do you think you could call me back, which she did. And so I think one of the most difficult things is isolation. I think when we talked about our veterans in Vietnam, I think knowing there was a guy that they could communicate with meant something. So I think that the reason that for instance, that I believe pets are a very big source of hope, a very big reason to get up every morning.

I think that people need connection. I think it’s very basic to hope. And for some people that connection can be their prayer. They believe in a higher power is what gets them through. And what’s good, what gives them hope for some people it’s nature. One person who had lost her mother said she didn’t know how she’d get through the next month. And then she saw an old broken fence. And she thought that makes me believe in the power of hoping, going on. So we invite people to use anything they can if they are not with other people. And I can’t underscore enough how important spirituality and pets and nature are in fueling hope.

Christin Thieme: That’s so interesting. I love that. That you, I mean, you mentioned those three elements: spirituality, pets, nature—the connection. Are there any other components of hope or something that you would encourage somebody to do as they’re trying to gain hope, especially? I mean, it’s easy to talk about having hope, finding a better connection, for the average person, but what about for those who are in really, extremely challenging, painful circumstances? How do you go about gaining hope?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: I think you break down the pathways that give a person agency into very small, doable steps. You know, they say the journey of a thousand miles begins with a step. I think if you have somebody who is recovering from a serious illness and literally, and I’ve seen it happen with my family, with other people, the fact that they sat up in that bed today, that’s a reason for hope. The fact that somebody gets to school, a very phobic kid, even though they don’t talk to anyone else, that’s a reason to hope. So I think you break it down to minute details.

I was once giving a program and I was sitting with a group of young people who had all had a sibling who had taken their lives, who had died by suicide. And they were talking about how do you manage, how do you hold onto hope? And someone said, you take it day by day. And I said, I’ve heard lately that people say they take it minute by minute. And one young woman said, sometimes I’m taking it millisecond by millisecond. And so it’s a perfect example of you look for any thread. Someone did an article, she worked in a hotline, at a hotline center for suicide. And she said she was in the business of holding onto slender threads of hope. And I think that’s how you do it, in tiny little steps.

Christin Thieme: Is there on the flip side, any danger in hope and having maybe a focus on what’s possible instead of what’s probable in your life?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Well, I don’t think there’s any danger in having hope if, in fact, you think of it as willpower and way power. If you hope that you’ll be fine, but you never take your medication, I don’t know that you’re going to be fine. It’s not magic. It’s action-oriented. I think that so many people now who are fighting for so many causes worldwide, and even in our country, they’ve interviewed them and said, do you feel badly that you’re not going to see a change in your lifetime? I think they asked Angela Davis, might’ve been one of the people, and the answer was, you’ll never see a change if you’re someone fighting for a change and you’ve got to see the result. Now you’ve got to keep doing it and believing, even if you don’t see a change in your lifetime. And that’s, I think that’s the propeller—the propeller about hope is believing in the possibility, even though you may not get to applaud the final end result.

Christin Thieme: Hope as a propeller. I like that. So I’ve shared a little bit with you about The Salvation Army’s Pathway of Hope—this initiative to really come alongside and join families in trying to solve the root causes of their own crisis, their own vulnerability, to increase their hope on this path to self-sufficiency and really to try to break the cycle of poverty for families, for their children down the line. So when you’re approaching hope from this programmatic perspective, I’m wondering if you could just weigh in a little bit as part of programs, part of a nonprofit, somebody coming alongside someone trying to help impact somebody’s life, what must be considered when you think about it from that perspective?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: So to me, there’s two things. One is, you know, when someone says it’s not only an economic poverty, it’s a poverty of spirit, a feeling of low self-esteem, I think we have to approach it with real respect. I think that part of the respect people feel is that programs like yours are saying, we respect you as parents, as people who want your children to be okay, and we’re going to enable you to be the kind of parent we know you want to be. And so I think if you foster a sense of agency and pride in them being able to help their children out of poverty, you give them a great gift and we shouldn’t overlook your very presence, Christin, whatever the components of a particular program. I think the presence of someone who believes in you is a very big part of the gift because it shows respect, and it shows our belief that they can do it. They can do it with even a small amount of change or even whatever ingredients we give them because we know—who’s more important to a child than the parent? So enabling them, I think, is a gift to them that they pass forward.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, absolutely. I like that too. That is a big key is just to believe in someone and help them believe in themselves. What about for anybody listening today? How can someone go about improving their own hope today? What would be your one most tangible tip or piece of advice for improving your hope today?

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Don’t ever assume today is the end of the story. And if today doesn’t feel good, but you dare to consider that you’re going to try something tomorrow, then you’re harnessing hope. If you dare to consider connecting with somebody, your mood will shift. If you dare to consider helping someone else, your own sense of hope will be fueled because this is all about passing it forward. And it’s like one of the people say sometimes to hope under the most extreme circumstances is an act of defiance that permits a person to live his life on his own terms.

Christin Thieme: Well, Dr. Phillips, thank you so much for sharing today. Thank you for the work that you’re doing in the world, and thank you for helping us all to see hope and a new light.

Dr. Suzanne Phillips: Okay, you’re welcome and the best with your program. It’s a gift. I’m sure it’s going to enable people to step out of poverty to give their children a chance and hope.

I hope you’re now inspired to find a bit more of that propeller-like resiliency of hope in your life—and ready to help spread it around.

Next week, we’re taking it back to the beginning of the initiative to hear more about how Pathway of Hope came to be and how it’s different from what The Salvation Army has always been known for.

Until then, keep on doing good.

Additional resources:

- Subscribe and listen in this season to the Do Gooders Podcast with episodes 88-94 focused on exploring the Pathway of Hope.

- Connect with Dr. Suzanne Phillips.

- You’ve probably seen the red kettles and thrift stores, and while we’re rightfully well known for both…The Salvation Army is so much more than red kettles and thrift stores. So who are we? What do we do? Where? Right this way for Salvation Army 101.

- Get inside the Caring Magazine Scripture Study Collection and find a suite of free, downloadable Bible studies to guide you through topics from New Beginnings Through Forgiveness, to Understanding our Imago Dei or Life Hacks From David.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.