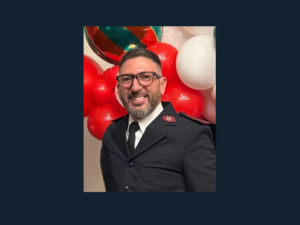

In our recent episodes, we’ve explored what it means to lose home—from the immediate chaos of evacuation to the grief of loss, to the challenging work of supporting a community in crisis. Last week, we talked to Captains Nick and Becky Helms, who lead The Salvation Army in Pasadena, California, about ministering to their congregation in communities affected by the Eaton Fire while also processing their own family’s displacement.

Today, we’re examining the deeper psychological impact of disaster on communities.

Dr. David Eisenman has spent more than two decades studying how disasters affect public health and community resilience. As director of UCLA’s Center for Public Health and Disasters and a practicing physician, he brings both research insight and frontline experience to our conversation about healing after loss.

We discuss how communities can support one another through trauma, what the long-term effects of displacement look like, and how we can build resilience in the face of increasing natural disasters.

Show highlights include:

- How communities process collective trauma after disasters like these wildfires.

- How the loss of familiar landscapes and gathering places affect a community’s psychological well-being.

- Unique mental health challenges seen urban wildfires like these, where the destruction happens in densely populated areas

- What community leaders and aid organizations should prioritize in these early days.

- How families can help children process this trauma.

- Patterns in how communities rebuild emotionally.

- How to care for your own mental health in the coming weeks.

- What gives Dr. Eisenman hope when looking at communities recovering from disasters.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Dr. David Eisenman: I’m what someone just called today a purple unicorn because I’m a general internist, your primary care doctor type. I’m a board-certified general internist, have been for 30 years, but I’ve been doing disaster research for 25 years. And a lot of that is on some of that time mental health, which is sort of the purple part of the unicorn. Because I’m not just a doctor doing public health, disaster research, but also some of it’s mental health.

But a lot of it is on other topics. Why do people evacuate? Why not? Why don’t people evacuate? What is recovery all about? What are the risks and exposures and challenges and road that people face after an event like this? What’s the loss of the environment and the forest mean in a community like this? That’s a particular interest of mine.

So I work at UCLA where I’m a professor of medicine and a professor of public health. I’m in the division of general internal medicine and health services research. And I also then direct the Center for Public Health and Disasters and co-direct the Center for Healthy Climate Solutions. The second of those is more focused on climate change and health, but the two topics really overlap and are topics that are of high demand at this moment in the region.

Christin Thieme: Given everything that you do, the work that you do, the research that you’ve done for so many years, what’s kind of an overview of what you’ve learned about how communities process what you could call a collective trauma after disasters like these wildfires?

Dr. David Eisenman: It is indeed collective trauma. And that’s a very good framing of it because what that does is right away tell you, how do you compare it to other, how do you look at other collective traumas and the recovery and the expectations and the timeline from other collective traumas? So, like collective traumas that hit communities include disasters of all sorts.

Natural disasters like hurricanes, earthquakes, kind of mixed disasters like this, like a wildfire, I’m not saying that’s natural or manmade, it’s Fully manmade ones like 9-11, or you’re kind of unfortunately more routine, even industrial leak that’s toxic to a community.

We’ve seen a lot of those in the last, you know, in the decades. All those end up being collective traumas for the community that threaten the physical health, threaten the life of people who live there, all members of the households that live there, all the households that live there, no matter how well protected they may have thought, how well resourced.

It may face a threat to life and limb of themselves and family members. If they themselves didn’t actually face the direct threat, they witness it. They’re anxious that they have for a while. They don’t know. They have close family members and friends that have directly witnessed it.

So there, and there’s lots of layers and levels of this kind of constant of this exposure. And you can look at it both at like the sort of individual level, I’ve described at the individual level and the, maybe the family level just now. You can also look at it at the community level. And so when it happens to entire neighborhoods and entire communities, there you’re looking at really, you know, the loss of the social connections. The loss of all the resources that people shared and that brought them together and that it was a commonality.

There was a source of memories, of pride, of enjoyment. You know, here in Los Angeles, one of the things we’ve lost is the outdoors, the mountains, parts of the mountains around us. And this is a shared resource that everyone, know, one of the reasons you live in Los Angeles is to go into the mountains easily.

So there’s kind of a collective trauma around this loss of something that we can socialize with all the time and brings us emotional support and brings us psychological support.

Christin Thieme: Like you said, that the effects have been so widespread. Everyone that I’ve talked to in the past week and a half or so have know somebody directly who has lost their home, not only those who were under mandatory orders to leave their homes, but who’ve actually lost their homes. And we’ve been talking a lot on the show about how it’s more than just the loss of stuff, right? It’s that sense of safety and anchoring that is your home and what happens when that goes away. So what unique mental health challenges you could say, what do people in this area, especially in urban areas where it’s densely populated, what are the unique challenges that you see in cases like this after a wildfire, this type of disaster when the destruction is so widespread.

Dr. David Eisenman: Yeah, and I’m really glad to hear you talk about it in terms of homes because that is, it’s not a house, it’s a home, right? And that brings with it all the emotional and spiritual and psychological and physical valence and safety that home means to us. That’s what people have lost. I think what’s unique, I want to expand on this idea of what’s unique in terms of losing the mountains.

I’ll tell little story. A decade ago, I went to study five communities that surrounded this large national forest in Arizona. And the national forest had burned. Was the Wallow Fire. And the five communities are all around the periphery of it. And before doing any kind of survey of the trauma, the mental health consequences,

One researcher like myself goes and just talks to people in the community just to get a sense of what the salient issues are, what’s their priorities, what should I be surveying on? And every one of those towns, they were miles apart from each other down the road, I talk to people and they say the same thing. I feel like I’m grieving the loss of the forest. And I’m a primary care doctor and I’ve dealt with a lot of patients who have grief and bereavement, who’ve lost a loved one.

And it was exactly the same emotions, exactly the same affect and face and sound as someone saying I just lost my husband or wife. And so I really emotionally took that in. I could hear the word grief was not exaggerated. This was a form. This was a feeling of grief, the experience of grief. They were having the loss of the forest.

And it turns out there’s I had not really thought about this, even though I lived in Los Angeles, that when you live close to the forest or any other kind of environmental treasure that’s the reason you live there or part of the value of it, it brings you so much value. It brings you, you know, it’s the place you go to hike on your own just to clear your head. It’s the place that you go with your spouse to have a long conversation and just center things again. It’s, you know, your happy place as we’re fond of saying in my family. It’s a place where you meet friends to socialize without going out to a restaurant and eating, but you want to just walk and talk.

For, you know, in a bigger forest, like a national forest, it’s a place where people make their, some of their income, right? There’s whole industries around recreation and sporting and wildlife that get their income from the forest. So the loss is a tremendous loss that affects everything from the financial to the social to the psychological, emotional and spiritual. And it’s this loss of your treasured environment that’s really deep.

And there’s, it turns out, a philosophical term for it. A philosopher named Glenn Albrecht coined the term solastalgia. And it’s the grief one feels at the loss of a treasured environment.

And so we actually decided to measure solastalgia in a survey. And what we found is that people who scored higher in solastalgia had more aspects of solastalgia that they were experiencing. And this was like nine months or 12 months after the fire. Those same people had higher levels of psychological distress. And that, you know, in math, in statistical equations that adjusted for differences in income and adjusted for how much income the family had lost and other factors that we know make a difference in the level of psychological distress you have later on. Solastalgia was still highly associated with your psychological distress.

So my point is, I think that we’re going to experience that here. I know we’re experiencing that here in Los Angeles. I’m a New Yorker. moved to Los Angeles and my New York friends are always like, you know, what do you see in LA? And the first thing I do when I, when they come here is I take them on a hike and I let them experience what I love. That’s 20 minutes from my home that I do every week that makes me see LA differently every time in its beautiful aspect. And we’ve lost that. At least for a period of time, it will grow back, but it will be several years till it’s the same. And it will be certainly a year until it’s accessible in the same way.

It doesn’t compare to losing your house, your home. I recognize that. But it points out that the trauma of this event extends beyond those who have lost their home to encompass our whole community. And that’s what’s really distinctive. One of the things that’s distinctive about these LA fires.

Christin Thieme: Definitely. Yes, it’s just so widespread. In the immediate response phase, what from your perspective should community leaders, aid organizations, The Salvation Army is there on the ground. What should groups like this be prioritizing in terms of supporting people in these early days?

Dr. David Eisenman: Well, we and your organization know very well what people need in the beginning is physical safety, right? They need the Maslow hierarchy. So, you know, people are needing all the safety of home and the centeredness of a home. And that’s a real issue for, it’s going to be a real issue for quite a while. There was already in Los Angeles, a very tight and expensive rental market, you know, and as expensive as anywhere in the country, more expensive. And so that’s just going to get harder. You know, there’ll be temporary shelters put up possibly. Those are hard to live in for too long. People are going to want to reenter their communities and start to rebuild. And there’s going to be real challenges in that. The ground is toxic where those buildings went down. All that paint and electronics and plastics that we store in our garages that now burnt and went leaching into the soil and is in the ash in the homes that were burning down, that’s toxic stuff. Until that’s remediated and gotten rid of, it’s dangerous. You have to take care, take caution going back into your home.

So I would say that one unique thing that we can be doing beyond the sort of housing, food, warmth, job, financial part, which is really well taken care of by groups like The Salvation Army, is making sure that people know how to stay safe as they reenter their neighborhoods. That they know, you know, how to reduce their exposure to these toxins, to wear an N-95 mask, because you can breathe it in, to wear gloves, to wear a set of clothes that you then take off before you go back home, because you don’t want to trail that ash and dust and toxin into your car and into your house. So change your clothes or wear some big white PPE outfit when you go into the rubble, but do something to isolate those two parts of your daily life.

That’s probably one thing we can get more education to our public on. And similarly, to make sure that our workers who go into those areas are protected. A lot of the workers in these sort of situations are end up being low-wage workers who may not be represented by a group that’s protecting them and are not offered the protections they need to do this work. You know, they are paid by the hour and they’re not offered N-95 masks and not told about these precautions and then are exposing themselves and then their family if they take the toxins home.

I think it’s really important, just as an example, I think it’s really important that we insist and help provide these kinds of protections to the workers that are going to be helping our communities dig out.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, absolutely. On a more personal level, what’s your advice to parents, especially as we’re ourselves feeling the anxiety of all this? As we’re recording this, there’s still all these warnings and particularly dangerous situation labels being put on to everything and the fires are still burning.

But our kids are experiencing this in their own way. I’m not in an evacuation zone, but I still had a 4 year old start crying at bedtime the other night that the fires were going to get us and kind of made me realize, like, OK, they’re hearing all these things and taking it in as little kids would and not understanding. So what’s your advice to parents about how we help kids in the area start to process all of this?

Dr. David Eisenman: Yeah, I think it’s really important to first just reassure frequently and routinely that the child is safe, that you are safe. If that in fact is the case, that they are safe. And it doesn’t have to be special times. You can just say it at routine times, you know, while you’re playing. Let’s, you know, you’re safe to go out. We’re safe to go outside and let’s go for a walk. It’s safe here. You know, when you go to bed, we’re together, we’re safe. Good night.

I think one particular thing I want to highlight is social media. The social media now for disasters has become its own kind of toxin. It used to be that five years ago, social media provided an opportunity to get really helpful information and resources during a disaster from community members, from responsible agencies, from neighbors.

Unfortunately, that’s been flooded out by people who use the disaster to promote political agendas or other agendas and to lay blame where it’s really too early to assign blame, to make something like the LA fires a pinata, a political pinata for something that’s on your agenda already. And it doesn’t take very long to be scrolling through social media to feel that toxic feeling of, they’re really, should I feel angry at these people? Did they make mistakes that harmed me? Can I trust them in the future?

And so you quickly lose any kind of opportunity to trust and to therefore allow yourself to get the useful information that people are trying to get to you, that the people who are in charge, whose jobs are to make you safe. You lose that resource, you’ve blocked yourself off from that.

Bottom line, limit people’s social media. It’s self-traumatizing.

Christin Thieme: Definitely. I know that feeling you’re talking about. When we start to look more long-term, you’ve researched multiple disasters in your career. What have you seen in the patterns, if anything? What have you observed about how communities go about rebuilding emotionally when there is so much of that collective trauma?

Dr. David Eisenman: It’s a difficult process. And I don’t think our field, the fields of mental health, public health or disaster mental health or all sort of cousins of each other have really succeeded yet in fully mastering this. We do know that there’s enormous need after a disaster like this.

There’ll be, know, studies have shown a year that a year from now, 20-30 % of the community will have diagnosable or at least symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of new depression, new anxiety, new post-traumatic stress disorder brought on by the wildfire. And that that will last for a number of them even five, 10 years later.

While the numbers will get better over time, even just naturally, there’ll still be higher numbers than there would have been without the disaster five years later.

You know, there already are plenty of organizations offering crisis hotlines and crisis response. In the early phase, those are being announced and they’ll be made available. It’s never enough. As time goes on, they kind of dwindle, but people still have the problems of all of these mental health problems.

And they either don’t know they have a mental health problem. They don’t know that the suffering they’re experiencing is mental health. You know, if you’re feeling anxious and your heart is pumping sometimes and you get a headache and you’re getting a stomach ache and you’re sweating and you’re not sure why, you’re feeling in your body, you go to your doctor and you ask them, is your heart okay? And they say, yeah, your heart’s okay. But they fail to ask about your experience in the wildfire and if you’re having anxiety or PTSD now.

So it’s really useful for people who have experienced this disaster to be made aware that they may experience diagnosable conditions like anxiety or PTSD, and they should ask their doctor, their primary care doctor about that, because primary care doctors can help you with it.

The mental health system in our country is very broken. A lot of insurances are not great at covering mental health needs. And a lot of our mental health providers, for instance, psychiatry, you see a lot of providers who only take money out of pocket. They don’t take insurance. And there’s just not enough of these psychologists and psychiatrists even still, even if they all did take insurance, there’s just not enough for the need.

So quickly, we have this baseline of difficulty accessing because you’re not insured, you’re poorly insured, they’re hard to reach, they don’t accept your insurance. And then there’s more need. And on top of that, people don’t recognize their need even still.

There’s been efforts at doing kind of collective large scale or larger scale approaches to mental health treatment in communities. I’m not so sure how strong the evidence is on those. That’s an evolving science. We really need to get better at our collective programs, more evidence-based and more widely available.

Christin Thieme: You’ve mentioned limiting social media. What other steps would you recommend to people in these next days, weeks, months that they take to protect their own mental health with all of that in mind?

Dr. David Eisenman: You know, I would do one thing that I did that just protected my mental health or just bolstered my mental health, which is the other day I went out to the local grocery store and bought a whole bunch of food and dog food and drove it across the street to a drop-off center for donations to evacuees. And I unloaded it and I put it on the pallets that they had set out there. And I talked a little bit to the people who were supervising the collection. And I talked to my other community members. And I drove away feeling so much better.

And what I realized is that I was doing a couple of things. One, I was doing the thing that everyone else says you should do, which is volunteer, and that it really makes you feel good. That the payoff is immediate. And two, I was connecting to my community. People I didn’t know, and I’d never see again, but I was connecting to my community for those 10 minutes while I was doing all this.

And you know, the whole thing took me less than an hour. I didn’t have to sign up for a shift in an evacuation center, which right now I can’t fit into my work schedule. But it was itself really valuable to the recovery effort, the response recovery effort, and was just brought me such psychological benefit. I look forward to doing it again this weekend. So it’s pretty ad hoc, but it seems the benefit seems to be really enormous and surprising.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, absolutely. And we are constantly of course, posting ways people can get involved and do good right where they are, especially if they’re in the Los Angeles area, but beyond that as well. So if you head to salarmy.us/socalfires, you will find constantly updated info there about how you can get involved. Finally, Dr. Eisenman, last question for you. I’m just wondering if you could share what gives you hope when you look at communities recovering from disasters, who are already farther down that path?

Dr. David Eisenman: What makes me actually excited is that more communities like Los Angeles in their thinking, think long-term in their rebuilding and in their planning. We have competing pressures. We do have to get people back into their homes, back into their daily lives as soon as possible. And that’s a pressure. That is paramount.

But at the same time, no one wants to rebuild and put themselves at the same risk. Many people will see this as an opportunity to rebuild in a way that improves our communities, reduces our risk in the future to these climate events that are happening in surprising ways like this. I mean, this was very much surprising, right?

Burning down the downtown of Altadena, miles away from the mountain, was never on anybody’s—not many people’s radar for a wildland urban interface fire. It quickly became an urban conflagration. That was just not something many people had talked about. So we are going to take this as an opportunity to rebuild in ways that protects us from climate change events that are here and happening in surprising ways and to really think out of the box as we say and rethink, what could that look like?

I don’t know, pie in the sky? Might it be rebuilding homes in ways that are more fire-resistant further away from the forest? People in the forest know how to create, how to build and do build fire-resistant homes. Now, maybe we need to have a larger perimeter of fire-resistant homes that we build. Maybe we need to even have some buffer land between the mountains and rebuilding area. I’d like to put that out there as an opportunity for creating a future that we all like better.

I’ve seen that happen in communities like the communities around Paradise after the Camp Fire, building community centers and capacities that really improve the community, that are making it more resilient. And I hope we can do some of that in Los Angeles.

Additional resources:

- If you are one of the hopefuls, get on the list for the Do Good Digest, our free 3-minute weekly email newsletter used by more than 20,000 hopefuls like you for a quick pick-me-up in a busy day.

- If you are enjoying this show and want to support it, leave a rating and review wherever you listen to help new listeners hit play for the first time with more confidence.

- If you want to help The Salvation Army serve more than 24 million Americans in need each year, give today. Your gift of money, goods or time helps The Salvation Army do good all year in your community.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.