Even in the midst of unprecedented secularization, several factors keep young adults tied to church.

By Mindy Farabee –

American church denominations have heard a familiar story in recent years: the ranks are eroding.

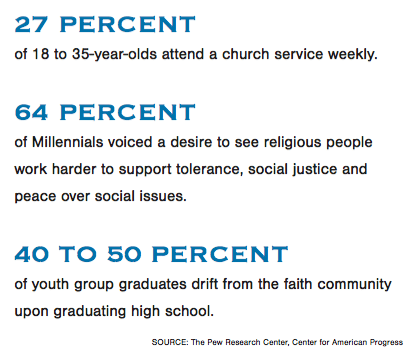

Across denominations, 40 to 50 percent of youth group graduates are drifting from the faith community upon graduating high school, while just 27 percent of young adults 18 to 35 years old report attending a weekly service, according to the Pew Research Center.

By any measure, this group, known as the Millennial generation, is on the vanguard of a growing secularization remaking the country’s religious communities in profound ways.

The whys and wherefores behind young Americans’ steep decline in church attendance remain complex. Sheer numbers paint a sketchy portrait of huge cultural shift still very much in the process of shifting—some experts contend the statistics are overstated, and as of late, the downward trend could be showing evidence of reversing, as Millennials mature and begin returning to the church—yet the questions these trends pose are fundamental questions about the future of organized religion.

While the “religiously unaffiliated” now outnumber both Catholics and mainline Protestants across generations, researches have long studied Millennials’ religious views and changing relationship to the church, exploring everything from the physical design of worship centers to the technology of tithing. A picture has emerged of a generation generally disinclined to join institutions, distrustful of its leaders and disenchanted with hardline moral stances—while nevertheless maintaining some very traditional views about how religion should be practiced.

Sunday School in danger

“It’s a multi-faceted equation,” said Captain Keith Maynor, national youth secretary. “The research right now is pretty clear that, if you’re a Millennial in the United States today, you’re going to have an aversion to institutions. And that includes all institutions, whether that’s marriage, belonging to a political party or…a service group like a rotary club or having a denominational identity,” Maynor continued, pointing to a 2015 study on changes to the country’s religious landscape conducted by the Pew Research Center. “To think that young Salvationists are not touched by that, not influenced by that, is kind of wishful thinking.”

According to Maynor, the conversation around declining membership has touched every level of leadership in the Army. It’s also taken on an increased urgency over the past four years. “We are in organizational decline when you look at the national picture, across every territory,” he said. “[W]e’re at a point where, if we don’t do a turnaround into a very strategic comprehensive change to the way we do ministries, Sunday School is in danger.”

The generational shift away from organized religion got under way beginning in the late 1990s, coinciding with the larger cultural shift that began to view Christianity—and evangelical Christianity in particular—with greater skepticism. In a study conducted last year, 87 percent of Millennials who don’t go to church reported finding Christians judgmental, with a nearly identical amount (85 percent) believing Christians are hypocritical, and a large majority (70 percent) calling them insensitive.

Those kinds of statistics probably wouldn’t surprise Lt. Caroline Rowe, youth and candidate secretary for the Golden State Division. When Rowe arrived at her post last July, it was after three years as a corps officer in Modesto, Calif., where she had inherited a young adult group comprised of two participants. There, she decided to institute a new, weekly young adult Bible study imbued with her own earnest and open-hearted style.

“It was funny how people started coming, even if they didn’t come to church,” she said. “I had a lot of welfare-to-work, single mothers who were just looking to find truth.”

Some told her they felt judged in church on a Sunday morning, “but they would come on this one young adult night, and all we did was open up the Word, and we would go through the books chapter by chapter saying, ‘What do you think this means? What does this mean?,’” Rowe said.

Soon, the young adult group grew to a dozen participants. Looking to build on that experience when she took on a divisional role, one of her earliest moves was to work with leadership in putting together an open forum at the annual Golden State youth retreat, where this past January she sat down with a group of teens to ask tough questions.

“I said, ‘what are we doing right and what are we doing wrong?’ And this was their number one thing—we’re being made into leaders and nobody is discipling us,” Rowe said.

Indeed, help devising a “holistic” faith—one that isn’t relegated to once-a-week worship—as well as one capable of drawing connections between Christian callings and secular work, are key factors in why young adults remain with their church, according to a 2014 study by the Barna Group. Also, relationships matter.

Intergenerational ones in particular, said Kara Powell, executive director of the Fuller Youth Institute and its “Sticky Faith” initiative at Fuller Theological Seminary. That’s what researchers found in the Institute’s three-year longitudinal study. There, they followed 500 youth group graduates through their first three years in college, factoring in 13 different participation variables to identify correlations between typical youth ministry programs and spiritual maturity in high school and college.

“Of the 13 variables we looked at, the one most correlated with mature faith and ongoing faith in college was intergenerational relationships and worship,” Powell said.

In response, Powell said the Institute began recommending a “new ‘5-to-1 ratio’” between generations. That doesn’t mean bringing in five additional Bible study leaders, she said. “The downside of [a recent trend in the specialization in children’s and youth ministry] is that churches can tend to feel they can outsource the spiritual formation of their young people to that better-trained, more devoted children’s and youth ministry specialists.”

Rather, Powell’s team has something just as intentional, but more fluid, in mind. “We’re talking about five adults who are, as we say in our family, ‘on your team,’” she said. “Five adults who show up at your important events, five adults who are praying for you and supporting you and your whole family.”

Otherwise, “when kids graduate from youth ministry, they don’t know the church, they know the youth pastor,” she said. “By creating more intergenerational relationships, kids have a context for the overall church.”

The questions these trends pose are fundamental questions about the future of organized religion.

Feeling fully integrated can help ease transitions. Rowe, for instance, sensed that her young adults were getting lost in the shuffle, neither mentored as youth in troops nor teens in corps cadets, but rather abruptly relegated to reinforcements for church officials—which left them feeling ill-prepared for expectations suddenly placed upon them.

“They said, ‘we really want someone to go through the Word and sit down and teach us what the Word means now and why we believe what we believe,” she said. “‘We don’t want little Sunday school lessons; we don’t want a little devotional before a band meeting;’ right, and that’s what was happening.”

When it comes to Salvation Army culture in particular, the research intersects in noteworthy ways. For instance, findings about the importance of durable, intergenerational bonds, can shed some interesting light on long-held Army practices, such as transferring out officers every four to five years. And as one of the most diverse denominations in North America, its makeup looks more like the face of the Millennial generation itself—the most diverse this country has ever seen. At the same time, the Army’s substantial tradition of active service could offer a compelling approach for a generation that prizes community building and social justice work—fully 64 percent of Millennials surveyed in a 2009 study by the Center for American Progress voiced a desire to see religious people work harder to support tolerance, social justice and peace over social issues.

Yet it’s not always apparent how to best integrate a faith experience with social work.

“We are very well positioned to do that kind of activity in the community, whether it is advocating for victims of trafficking, or simply providing groceries,” Maynor noted. However, while the opportunity for every Salvationist to participate exists, within the Army’s large social service ministry, “there can be a tendency to say to a social service client, ‘just wait right here, I’ll get someone else to help you,’” he said. “Salvationists could fall into a reliance on specialists who are doing that full time as professional social workers. We can easily fall into the trap of thinking, ‘I celebrate our social work, I appreciate it, but I don’t have to get my hands dirty.’”

The importance of doubt

Catholic novelist Graham Greene once famously referred to his faith as “doubt of my doubt.” Religious philosopher Jonathan Sacks, Britain’s former chief rabbi, came at the issue this way: “In Judaism,” he wrote, “to be without questions is not a sign of faith, but a lack of depth.”

That disbelief has always been inextricably bound up with belief is not just par for the course. What’s more clearly understood now is how that very struggle can actually strengthen young adults’ religious experience.

“If you were to ask me what was one of the biggest surprises in our Sticky Faith research, it would be the importance of doubt,” Powell said. “What we found was that when young people have the chance to express their doubt and explore their doubt, that’s actually correlated with greater faith maturity. Or put more simply, doubt isn’t toxic to faith—silence is.”

Seven in 10 young adults surveyed by the Fuller Youth Institute have expressed reservations about their faith. And while encounters with different cultures and religions provoked some rethinking, according to Powell uncertainties were just as likely to surface in the face of personal suffering.

“Giving them a chance to express that is really important,” Powell said.

In Rowe’s experience, that’s an arena in which The Salvation Army could better engage. Rowe works to incorporate a gentleness in her young adult ministry, creating an environment where gaps between classroom teachings and personal experience can be successfully bridged.

“Just giving them an area of trust and nonjudgment, where you can say, ‘I don’t care who your dad is, if you don’t believe God is real to you now, because it’s just been taught to you but you haven’t experienced it for yourself, that’s okay,’” she said. “‘Let’s walk through that.’”

How to walk together through this next phase is, in some ways, what it all boils down to. In an effort to better explore that, over the coming months New Frontier Chronicle will be publishing a series of articles looking at retention issues and initiatives within The Salvation Army, efforts both big and small, that speak to how the organization is connecting with its next generation. When young adults choose to stay, what’s driving their commitment? And how might that impact the future shape of The Salvation Army?

In the scenarios to be highlighted—just a few of many creative responses—it’s less one-size-fits-all solutions than new paths for engagement that are emerging, different expressions of a similar mission, all with the same underlying theme.

And all underscored by the same principal. “Ultimately, one of the best solutions is when local leaders are faithful to the Lord and they are faithful to the Word of God,” Maynor said. “There is no substitute for exemplary local leadership. The Salvation Army could be blessed with the best ministry strategies, but if we do not have humble and efficient local leaders, we will not be rendering effective ministry that reaches children, adults and families.”