America is one of the most religiously diverse countries on Earth and yet we remain dangerously ignorant about religion.

In a 2010 survey, the Pew Forum asked more than 3,000 Americans some simple questions about the world’s religions. Most respondents could answer only half of them correctly. A 2005 study conducted for the Bible Literacy Project tested teenagers’ ability to name the five world religions of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Only 10 percent could name all five and 15 percent could not name any of them.

This is bad news for a democratic and religiously plural society like the United States. Religion is not a discrete and ahistorical phenomenon. The world’s religious traditions are woven into the very fabric of human history and culture. Not only are religiously illiterate students ill equipped to compete in a global marketplace, they are deprived of the cultural heritage that is their birthright as human beings. Without some understanding of the world’s religions, students will not know the traditions and values of their neighbors and coworkers, understand literary and cultural references, or be able to interpret claims about religion made by politicians and the media.

The place to combat this problem is in the schools. Contrary to popular belief, there is no law that forbids the discussion of religion in public schools. In the Supreme Court decision Abington v. Schempp (1963), which banned devotional reading of the Bible in public schools as unconstitutional, Justice Thomas Clark remarked, “It might well be said that one’s education is not complete without a study of comparative religion or the history of religion and its advancement of civilization.” This distinction between the state-sponsored practice of a religion and education about religion has been reiterated in subsequent decisions (Stone v. Graham, 1980; Edwards v. Aquillard, 1987).

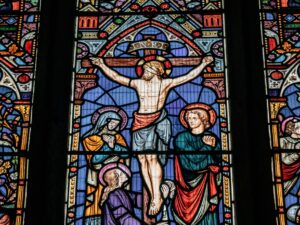

Even the militant atheist Richard Dawkins echoes Clark’s opinion regarding religious education. In his polemical work The God Delusion, he argues that students must have some familiarity with the Bible because without it they will not be able to appreciate Western art or literature. Most states actually mandate that students learn about world religions as part of their standards for world history. Many state standards for language arts specify that students should learn to analyze the use of Biblical themes and references.

Why then, do we remain a nation plagued by religious illiteracy?

Before I became a religion professor specializing in American religious history, I was a social studies teacher in a public high school. This experience allowed me to observe firsthand the obstacles for achieving religious literacy. The greatest problem is a general ignorance about the constitution and the legal and ethical issues surrounding religion in public schools. A second problem is confusion about the difference between teaching about religion and religious proselytizing. Historically, public schools have been places where students from religious minorities have been pressured to conform to the majority. Many parents, anxious to see their values and beliefs passed on to their children, would rather their children not learn about other religions at all.

Solving these problems will require a more informed public conversation about these issues.

Understanding the constitution

In my experience, students and parents as well as teachers and administrators are aware that there are restrictions surrounding religion in public schools, but often have no idea that these restrictions are based on constitutional law. I repeatedly encountered the myth that religion cannot be discussed in schools because “it might make someone uncomfortable.” But education often requires making people uncomfortable. As a white teacher working in a predominantly black high school, I was uncomfortable teaching about the history of slavery. My discomfort did not allow me to omit slavery from U.S. history curriculum.

Another widespread myth is that public schools have “banned religion” because the government is controlled by forces hostile to Christianity. While the narrative of anti-Christian hostility has proved politically useful, it’s not true––at least not in any systematic way. Religion has never been banned from public schools.

We cannot begin to address the problem of religious literacy until teachers and administrators have a better understanding of the constitution. The First Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The “establishment clause” is the basis for the separation of church and state. Since the 1947 case Everson v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court has interpreted this clause to mean that state and federal governments must remain neutral by not promoting one religion over another. The “free exercise” clause protects the freedom of citizens to practice their religion.

As Charles C. Haynes of the Religious Freedom Education Project explained, “In a nation committed to religious liberty, public schools are neither the local church nor religion free zones.” Unfortunately, because we do not understand the nuances of these two clauses, our schools sometimes act like the local church and a religion free zone simultaneously.

One Christmas a fellow teacher hung a banner in the school’s hallway reminding the students, “Remember Jesus Is Reason For the Season!” Another colleague, a biology teacher, ended a class on evolution a few minutes early and gave her students five minutes of free time to prepare for their next class. Two students began talking to each other about whether they believed organic life evolved or was created by God. The teacher stopped their discussion and told them they were not allowed to talk about God during biology class. These two incidents are emblematic of our failure to educate teachers about the First Amendment.

My colleague who hung a banner reminding students that Christmas is about Jesus has a constitutional right to express her religious views as an individual. The problem is that she did so in her capacity as a public school teacher. This meant that her speech became the government’s speech and threatened the principle of neutrality. The biology teacher was also Christian, but under the false impression that it was illegal to have any discussion of religion on school grounds. When she told her students they could not have a private conversation about God, she was restricting the constitutional rights of her students unnecessarily. Both teachers were dedicated to their jobs and wanted what was best for the school. The problem was that there was no mechanism in place to train teachers and administrators about appropriate policies concerning religion in public schools.

Professional development is already focused on numerous issues from class management, to preparation for endless standardized tests, to bullying. Some of this professional development time should be set aside to study the constitution as it pertains to the classroom. This is a necessary first step for solving the problem of religious illiteracy.

Teaching without preaching

In a religiously plural society, public schools can become places where religious minorities are urged to conform to the beliefs and practices of the dominant culture. In 1859, a 10-year-old Catholic boy named Thomas Whall was beaten in Boston’s Eliot public school for refusing to recite the Protestant version of the Ten Commandments. This incident resulted in an uprising of Catholic schoolboys known as the “Eliot School Rebellion.” A similar incident occurred this year at a school in Louisiana, where a Buddhist student of Thai descent was repeatedly told by his science teacher that Buddhism is “stupid” and that he must become a Christian.

Obviously, it is unconstitutional for a public school to attack the religious beliefs of its students. In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), Chief Justice Warren Burger argued that parents have a “fundamental right” to guide the religious future of their children. Unfortunately, some parents have taken the position that any discussion of religion in schools will undermine their ability to pass their values on to their children. Many schools that have initiated curriculum about the beliefs and practices of other religions have met resistance from parents who feel that simply receiving accurate information about another religion amounts to indoctrination.

I have found this to be the case especially when it comes to education about Islam. Many parents are horrified by the idea of their child visiting a mosque or interacting with a Muslim speaker. When I worked with a wonderful group called The Islamic Speaker’s Bureau of Atlanta (ISBA), they told me that past appearances at schools had been cancelled after hysterical parents claimed the ISBA is a terrorist organization.

In practice, the line between promoting religious literacy and proselytizing is not murky at all. There is a clear difference between telling students what other people believe and telling students what they ought to believe. After over a month of paperwork, I was able to bring in a speaker from the ISBA. She stuck to a preapproved script and gave the students accurate information about the varieties of Islam that can be found throughout the world. Afterward, she fielded some questions about everything from what the Quran says about Jesus to Islamic law regarding marriage. No one converted to Islam but the students did leave with a better understanding of their Muslim classmates––many of whom were refugees from Somalia, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

– Test your religious knowledge at Pew Forum

– Visit Religious Freedom Education for additional resources, including a guide to the First Amendment and related clauses.

– Visit a service in each of the five world religions.

Much of the fear parents have regarding religious literacy is rooted in the fallacy that students are encouraged to shop for a new religion. But the purpose of religious literacy is not to give the students the option of finding greater spiritual satisfaction outside the religious tradition of their parents. Rather it is to empower them with knowledge about the world in which they live. To provide no practical knowledge about Islam to a generation of students shaped by 9/11, two foreign wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Arab spring is unconscionable.

Democracy assumes that individuals will make decisions for themselves based on their own reason. Parents can guide the religious futures of their children and teachers can give them information about the world they live in and the tools to analyze that information. But ultimately it is the students that will inherit our democracy and draw their own conclusions about the moral and ethical issues it faces. This is another reason why religion should be discussed in public schools.

Studying the world’s religious traditions gives students the opportunity to explore “big questions” and cultivate moral agency. This not only enriches their quality of life but ensures the future of our democracy by creating an electorate that can think critically about what makes for a good and just society.

Everyone has their own beliefs