Now that the immediate threat has subsided, recovery efforts have fully pivoted to long-term mode.

By Caitlin Johnston –

The cameras turned away from Beaumont, Texas, weeks ago, chasing Irma, Maria, Nate and other devastating storms hitting the United States over a six-week period.

By October, Hurricane Harvey, which made landfall on the Texas Gulf Coast on Aug. 25 with windspeeds of 130 miles per hour, became a rare mention on the evening news.

That might have made what Captain Jimmy Taylor saw even more shocking: as his truck crossed over a bridge into Port Arthur on Oct. 6, more than a month after the rains stopped, he saw standing water as high as the middle of doorways.

“There’s still water there from six weeks ago. Good grief,” Taylor said. “We watch it on the news and we think the water is gone and everything’s fine. Down here, you see people are struggling even to hold on. They have to literally start over their lives, and that’s not national news.”

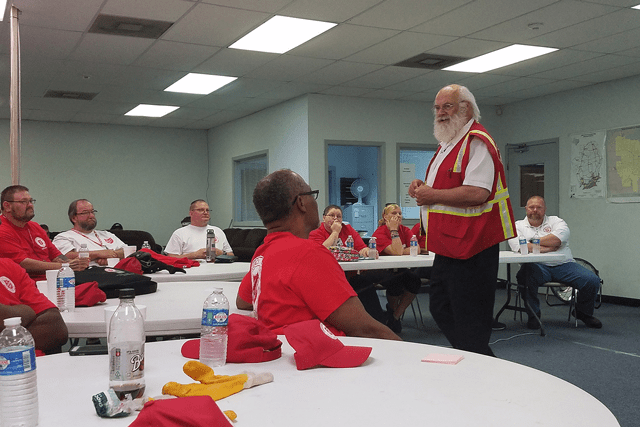

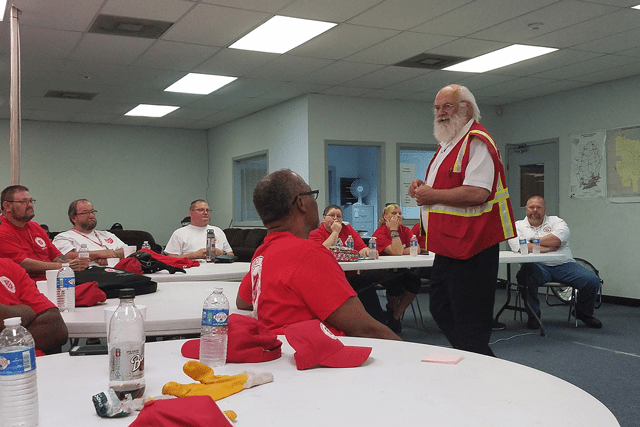

Taylor is the Incident Commander for hundreds of Salvation Army volunteers and staff who have come through the Golden Triangle—the area including Beaumont, Port Arthur and Orange—since Harvey hit.

Now that the immediate threat has subsided, recovery efforts have shifted to long-term mode. During Taylor’s time in the Golden Triangle, The Salvation Army stopped mass feeding hot meals and transitioned to handing out food boxes, personal hygiene products and cleaning supplies.

“We want to help people back to a sense of normalcy,” Taylor said. “While people are going back to the jobs and beginning to be able to eat regular meals, it’s still a struggle because it is such a high-poverty area.”

Beaumont’s demographics make recovery even more complicated, but that’s not unique to this hurricane. Dr. Bob Thomson, a post-doctoral fellow at Rice University in Houston, argues a disaster like Harvey does not create the most vulnerable of society—it exposes the level of their vulnerability.

“Those who can least cope with disaster tend to be concentrated in areas most prone to disaster,” Thomson said.

Beaumont, with a population of more than 117,000 people, is a prime example. The unemployment rate was at 7.2 percent in August, substantially higher than the 4.4 percent rate nationwide. One in five residents were living below the poverty line in 2015, the most recent year of data available through the U.S. census. The median household income is about $41,000 a year. That’s nearly 30 percent less than the average income nationwide of $56,516.

“It’s the people on the bottom—the poor, the working poor, the undocumented—they usually suffer the most in these situations,” said John Berglund, Western Territorial Emergency Disaster Services Director. “They’re the least resilient. It takes longer for them to bounce back than it does someone with greater means.”

Harvey didn’t blow down entire blocks of houses, but it did fill them with 50 inches of water, leaving them uninhabitable. People lost their houses, cars, personal belongings, and many of them don’t know where to begin again, Taylor said.

“It’s almost like the storm has gutted them personally and emotionally,” Taylor said. “They’re broken…Those demographics are really struggling to get back.”

The difference in recovery efforts for those with means and those without presents itself in different ways. Take flood insurance. Most of the areas hit hardest by Harvey are already prone to flooding. They’re also some of the cheapest real estate, meaning those looking for affordable housing often overlook the risk because it’s where they can afford to live. But while they can afford the rent, they can’t afford flood insurance.

“Those areas flood once a year, even without a hurricane,” Taylor said. “You and I see that, and we get flood insurance. They don’t have that resource, so they end up losing everything.”

For those who live in large houses that are insured, things work out, Berglund said. But especially for those without flood insurance or for senior citizens who have their house paid off and little savings, finding the money for repairs can be nearly impossible.

Berglund has seen it time and again with different hurricanes: Harvey, Sandy along the East Coast in 2012, Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. Those with the hardest time recovering were those who lived in low-lying areas, mostly because they had no other options.

“There are just some places where they shouldn’t be allowed to build,” Berglund said. “Or if they do build, they have to have stronger codes.”

Now that some of the most immediate needs have been met, Berglund said The Salvation Army is focusing on providing people with personal hygiene and cleaning supplies while also beginning the home repair process. Rapid repairs that will allow people to return to their homes, as opposed to staying in shelters or hotels, are key, he said. That includes everything from fixing electrical panels and hot water tanks to helping with mold prevention and removal.

According to Taylor, as many as 60,000 people were still in hotels early in October.

The Salvation Army has started case management operations as well, assisting people with everything from home repairs to employment to creating access to important resources. That part of the recovery process can take years, Berglund said. With Hurricane Sandy, for instance, recovery efforts there continued for three years, totaling more than $16 million.

“Can you imagine a direct hit where it takes the roof off your house and everything you own blows away? The concept for me is pretty devastating,” Berglund said. “The disaster in some cases goes on for another two, three or four years. These people are on a long trek to recover from this.”