If you’ve ever taken a trip on the London Underground, you cannot have missed the myriad signs pointing travelers in the direction of the “way out.” In operation since 1863, this network of trains ferrying passengers through the subterranean circuits would have been a well-established fixture of city life by the time William Booth’s most prominent work, “In Darkest England and the Way Out,” was published on Oct. 20, 1890. While I doubt Booth specifically had the metro in mind when he penned his tome, it’s certainly what comes to mind when I read it.

What was likely more resonant with Booth’s original audience was the “In Darkest England” element of the title—an obvious reference to Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s “In Darkest Africa,” which was published earlier that year and relates the tale of his now-famous quest to find Dr. Livingstone. Booth periodically alludes to Stanley’s work throughout the text, drawing explicit parallels between the atrocities committed by British colonials in Africa and the tragedies experienced by the poor in London: “Hard it is, no doubt, to read in Stanley’s pages of the slave-traders coldly arranging for the surprise of a village, the capture of the inhabitants, the massacre of those who resist and the violation of all the women; but the stony streets of London, if they could but speak, would tell of tragedies as awful, of ruin as complete, of ravishments as horrible, as if we were in Central Africa; only the ghastly devastation is covered, corpselike, with the artificialities and hypocrisies of modern civilization.”

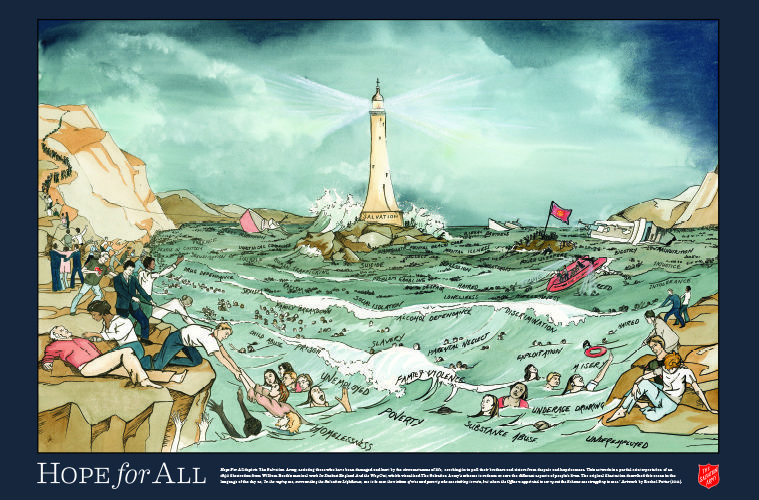

Booth had become well-acquainted with these tragedies through his years of outreach to the poor in London’s notorious East End, the same area where the Jack the Ripper murders took place in the fall of 1888. Although Booth often describes Darkest England as a specific geographic location in East London, it actually encompasses every slum in Britain marked by East London’s depth of poverty. Booth frames Darkest England as a shadow country within Britain, containing the segment of the nation’s populace that was homeless, starving or penniless, which he estimated to be around 3 million people. As this represented about one-tenth of the total population at the time, Booth identifies this group as “the submerged tenth.” To those who questioned his statistics, he offered this challenge: “If the evil is so much greater than I have described, then let your efforts be proportioned to your estimate, not to mine.”

Passion born of beliefs

Booth’s passion for assisting the lowest strata of society stemmed from a set of personal beliefs that gradually evolved over the course of his ministry. For one, he came to adopt the view that God’s will isn’t exclusively to prepare souls for the next life, but also to improve conditions and right injustices in this one—a role the established churches of his time had seemingly abandoned. “Why all this apparatus of temples and meeting-houses to save men from perdition in a world which is to come, while never a helping hand is stretched out to save them from the inferno of their present life?” he bemoans.

Another concept we find in the text is that of “soup, soap, salvation”—the idea that people cannot rationally comprehend or receive the gospel while experiencing the pangs of severe deprivation, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the fundamental premise of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, decades before that pyramid was conceived in the 1940s. While Booth doesn’t use this exact phrase, he does ask the question, “But what is the use of preaching the Gospel to men whose whole attention is concentrated upon a mad, desperate struggle to keep themselves alive?”

Finally, we see that Booth’s conception of holistic ministry regards practical service to others as an intrinsically spiritual act. When asked whether the social activities of The Salvation Army detracted from the spiritual as part of an interview for the War Cry in 1893, he remarked, “I know what you mean; but in my estimation it is all The Salvation Army proper. We want to abolish these distinctions, and make it as religious to sell a Guernsey or feed a hungry man as it is to take up a collection in the barracks. It is all part of our business, which is to save the world body and soul, for time and for eternity!”

The publication of “In Darkest England” marked a permanent shift in the orientation of the organization away from the purely evangelistic nature of The Christian Mission and toward the dualistic spiritual-social reform of The Salvation Army, crystallizing Booth’s perspective on Christian social responsibility and mirroring the social gospel movement that was occurring in America around the turn of the 20th century.

What distinguished Booth’s approach from other reformers of his time was his emphasis on both physical and spiritual regeneration. The service was a means of cultivating relationships with people that would hopefully eventually lead to relationships with Jesus. As Booth professes, “I must assert in the most unqualified way that it is primarily and mainly for the sake of saving the soul that I seek the salvation of the body.” Although this motivation has always been a hallmark of The Salvation Army’s work (sometimes attractive, sometimes controversial), Booth simultaneously makes it very clear that “no compulsion will for a moment be allowed with respect to religion”; spiritual support would be available, but voluntary.

Despite his wife, Catherine, having died of cancer a mere two weeks before the book was published, Booth offers a daringly ambitious and surprisingly optimistic approach to addressing the issues outlined in the first part of the book, dedicating three times as many pages to their remedies versus their effects. Consistent with his belief that solutions must be on the same scale as the problems they seek to address (one of his seven essentials for social programs), Booth’s proposal called for a dramatic social campaign to elevate the submerged tenth out of their deprivation. But to what standard were they to be elevated?

Minimum standard for all

Well before Franklin D. Roosevelt set forth his Economic Bill of Rights in 1944, William Booth tendered the Cab Horse Charter as the minimum standard of living for which to aspire for all of society’s members. In a rather clever analogy, Booth likens the condition of the poor to that of a London Cab Horse, exhausted from toil and neglect, but without any of the comforts or supports the horses are afforded. Booth articulates his minimum standard as follows: “These are the two points of the Cab Horse’s Charter. When he is down he is helped up, and while he lives he has food, shelter, and work. That, although a humble standard, is at present absolutely unattainable by millions—literally by millions—of our fellow men and women in this country.”

The mechanisms through which this standard would be achieved for his countrymen were varied and complex. Chief among the activities of his proposed social campaign were the colonies: the City Colonies, comprised of salvage brigades, salvage depots, industrial homes, factories, food distribution centers and shelters; the Farm Colonies, which would take people from the cities and redistribute them across plots of land in co-operative groups; and the Over-Sea Colonies, which would take members of the submerged tenth and transplant them to farm colonies across the British Empire.

“These are the two points of the Cab Horse’s Charter. When he is down he is helped up, and while he lives he has food, shelter, and work.”

William Booth

Well, as might have been predicted, the colonies, while bold and visionary, were largely unsuccessful. Often the land acquired did not lend itself to agricultural cultivation, and as it turns out, placing a bunch of city-dwellers who lack farming skills all together in one cluster is less effective than interspersing them among established, knowledgeable farmers. Consequently, the colonies lost a great deal of money and proved to be unsustainable.

Although the colonies didn’t progress exactly as prescribed in “In Darkest England,” each of them did produce residual activities of merit. The salvage depots and industrial homes of the City Colony became the thrift stores and Adult Rehabilitation Centers (ARCs) we still have today. The function of the salvage brigades, while still performed by ARC trucks and donation centers, is also performed by any charity or municipality that collects donated goods or provides residential recycling pick-up. While no formal Over-Sea Colony was ever successfully established, the effort to do so resulted in the creation of an Emigration Department that facilitated the migration of some 250,000 people from Britain to Canada, Australia and New Zealand prior to the end of the Second World War.

Ironically, the secondary aspects of his scheme, appended almost as an afterthought, have proven to be the more effective and long-lasting, many of which are now performed by other government and non-profit agencies. For example, Booth saw the need for affordable child care, “where for a small charge babies and young children can be taken care of in the day while the mothers are at work.” In his vision of a Whitechapel-by-the-Sea as a recreational retreat for those who “never get away from the sunless alleys and grimy streets in which they exist from year to year,” we see the origins of our summer camp programs. The rescue homes for prostituted girls continue on in the form of anti-trafficking safe houses.

Ideas live on

Some of Booth’s ideas have aged better than others. Certainly some of his statements are a product of the imperialist mindset of the times. One chafes when reading Booth’s description of Britain’s colonial holdings as “simply pieces of Britain distributed about the world, enabling the Britisher to have access to the richest parts of the earth” during his discussion of the emigration experience for the Over-Sea Colony (an ironic reversal from his earlier critique of the corruption of British civilization). On other points, however, he seems remarkably forward-thinking, as with his Cab Horse Charter and his ideas around community gardens, recycling, summer camps, employment agencies, prison diversion, restorative justice, legal aid, social science research institutes, matchmaking services for lonely city-dwellers, and banking services for the poor.

In reading Booth’s rationale for a Poor Man’s Bank, one can easily imagine how the often predatory practices of modern payday lenders might provoke the ire of Booth today: “At present Society is organized far too much on the principle of giving to him who hath so that he shall have more abundantly, and taking away from him who hath not even that which he hath…Someday I hope the State may be sufficiently enlightened to take up this business itself; at present it is left in the hands of the pawnbroker and the loan agency, and a set of sharks, who cruelly prey upon the interests of the poor…The institution of a Poor Man’s Bank will be, I hope, before long, one of the recognised objects of our own government.”

Booth also displays profound prescience in the arena of homelessness. In the section on “model suburban villages,” he reiterates the importance of establishing permanent housing situations for the poor, declaring that “one of the first steps which must inevitably be taken in the reformation of this class, is to make for them decent, healthy, pleasant homes, or help them to make them for themselves, which, if possible, is far better. I do not regard the institution of any first, second, or third-class lodging-houses as affording anything but palliatives of the existing distress.”

Before housing-first advocates get too excited, the latter portion of this section clarifies that Booth intended these suburban villages for those who had been stabilized in shelters and secured employment. Of course, he could not have foreseen the public housing subsidies or disability insurance programs used extensively today, so we should not be too quick to assume that his thoughts from a 19th century context would be identical to the ones he would form in a 21st century one. What we can deduce from this and other passages, though, is that Booth thought permanent housing should be safe, sanitary, affordable and appropriately sized for the number of occupants, and that people ought to be moved into permanent dwellings as expediently as possible.

While our methods can and must continue to adapt over time as our understanding in all branches of knowledge deepens, the direction that Booth provides for shouldering the cause of the marginalized serves as a timeless signpost to help The Salvation Army and the whole of society find the way out: “The dark and dismal jungle of pauperism, vice and despair is the inheritance to which we have succeeded from the generations and centuries past, during which wars, insurrections and internal troubles left our forefathers small leisure to attend to the well-being of the sunken tenth. Now that we have happened upon more fortunate times, let us recognize that we are our brother’s keepers, and set to work, regardless of party distinctions and religious differences, to make this world of ours a little bit more like home for those whom we call our brethren.”

Do Good:

- Read more about people who have impacted The Salvation Army in “Soldiers of the Cross: Pioneers of Social Change” (Crest Books, 2006) by Norman Murdoch and “Insane: The Stories of Crazy Salvos Who Changed the World” (The Salvation Army Australia Southern Territory, 2007) by David Collinson and Nealson Munn.

- See more about The Salvation Army’s work today, give to support the effort and find ways to join the fight for good.