In the words of French writer Antoine de Saint Exupéry, “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

In other words, cast a vision of what could be.

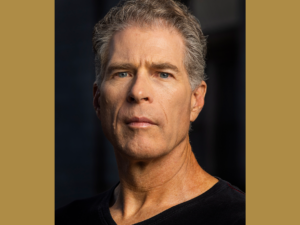

That’s exactly what Dr. Matthew Desmond is doing in his latest book, “Poverty, by America,” because the end of poverty, he says, is possible.

Dr. Desmond is a professor of sociology at Princeton University. He’s the author of four books, including “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City,” which won the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Critics Circle Award, Carnegie Medal, and PEN / John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction.

As the principal investigator of The Eviction Lab, his research focuses on poverty in America, city life, housing insecurity, public policy, racial inequality, and ethnography. He is the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship, the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award, and the William Julius Wilson Early Career Award.

A contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine, Dr. Desmond was listed among the Politico 50, as one of “fifty people across the country who are most influencing the national political debate.”

His latest book, already a #1 New York Times Bestseller, reimagines the debate on poverty, provocatively challenging all of us that the reason it persists in America is because so many of us benefit from it.

As he writes, “some lives are made small so that others may grow.”

But we can end poverty, he argues, and each one of us can become a poverty abolitionist.

Show highlights include:

- Why poverty is a subject that interests Dr. Matthew Desmond.

- The state of poverty today.

- The real-life experience of poverty.

- Why Desmond wrote his new book, “Poverty, By America”?

- What he means by saying poverty is a “tight knot of social problems.”

- Why we haven’t seen more change in poverty over time.

- What he means in writing, “To understand the causes of poverty, we must look beyond the poor.”

- What’s uniquely American about poverty.

- How we can approach the solution, starting with five ways to get involved.

- How we all benefit from ending poverty

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: Well, Dr. Matthew Desmond, welcome to the Do Gooders Podcast. Thank you so much for your time and joining us today.

Dr. Matthew Desmond: I’m thrilled to be here. Thank you so much for having me.

Christin Thieme: Absolutely. I’m excited to talk to you today about this topic. We’re doing a series right now on this topic and looking at the different aspects of really The Salvation Army’s work in many ways about hunger and about homelessness and recovery and all these different areas of work that we do. And you kind of wrote about all of it, so I’m excited to talk to you and hear your perspective on it. Let’s start there. You’ve really dedicated your career to this idea of how we can solve poverty in many ways. Why is it a subject that interests you?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: I grew up poor. Money was pretty tight around our home. We got foreclosed on when I was in college, and I think that that probably set me on this road. But there’s a part of me that just hates poverty. It hates what it does to people, the kind of health and life it steals from people, the way it blunts opportunity and diminishes us in a way. And so, I think that it makes me angry. I think the biggest myth about poverty in the United States is we have to tolerate it, we have to live with it, and it’s just not true. And so, I think that, when I see all this poverty around us, I see unnecessary suffering, I see wasted potential, and I see a country that has more than enough resources to do something about it.

Christin Thieme: So poverty is a solvable issue?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: It’s totally a solvable issue. When the Johnson administration launched the War on Poverty in 1964, they set a deadline, which is a historical fact I just love. They were like, “All right, in 10 years, we got this.” And they didn’t get all the way there, but they reduced poverty by half. They made a significant difference. And I think that we used to have these ambitions to wipe poverty clean away from this country, to abolish it. And I think that should be our goal, to abolish poverty, to eliminate poverty. Why settle for anything less? We can and should do this.

Christin Thieme: And yet, just a couple days ago, The New York Times had a headline, it said ‘Poverty Rate Soared in 2022,’ with new Census Bureau data showing that the poverty rate rose to 12.4 percent last year from 7.8 percent in 2021, which they said was the largest one year jump on record. So what is the state of poverty today? I know we threw the pandemic in there, which kind of skewed things a little bit on some of those numbers, but could you give us just a little bit of an overlay of, what is poverty in America today? What does that look like?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: Well, you saw these big jumps, because for about two years, we had a different country. In COVID, the United States responded with bold relief, through three massive bills. And those bills helped to drive evictions and homelessness and poverty to record lows. So the poverty rate for kids was cut by about 46 percent in six months—46 percent in six months.

Christin Thieme: That’s crazy.

Dr. Matthew Desmond: And through the American Rescue Plan, and especially the extended child tax credit. So the big jumps we’re seeing these days, that’s reversion back to normal. And I think that should break our hearts. We could have had a stronger demand of our country that we keep these incredibly effective relief bills, but we stayed pretty silent. And so, we’re now getting back to normal. And normal in America is a child poverty rate that’s not just higher than our peer nations, like Germany or Canada or South Korea, but it’s double, it’s double those countries. About a third of our people live in households making $55,000 or less.

Many of those folks aren’t officially poor, but what else do you call trying to raise two kids in Austin, Texas, or Miami, Florida, on $55K or less? So there’s a great amount of economic insecurity. There’s poverty above the poverty line, so to speak. And then, America also harbors this hard bottom layer of poverty. Some economists have estimated that over 5 million of us get by on $4 a day or less. That means they’re abjectly poor by global standards. This really sets us apart from other rich democracies, all of this poverty amongst all these dollars.

Christin Thieme: So that’s kind of the overview of where we are. I want to backtrack a little bit to your first book, ‘Evicted.’ You didn’t just study poverty for that book, but you actually lived in it with the people that you wrote about. So can you give us a little picture of, what does poverty actually look like, beyond the stats? We hear all the numbers, but what’s the real life experience of it?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: So poverty is not just a line, right? It’s this really complicated collection of often humiliations and pains and agonies. It’s chronic pain on top of homelessness, on top of telling your kids they can’t have seconds, on top of debt collector harassment, the suffocation of your talents and your dreams. It’s often serious health complications and death come early. So when I moved to Milwaukee to follow families getting evicted from their homes, I saw a kind of poverty that I had never seen before and that I had never experienced before.

I saw grandmas living without heat in the winter in Wisconsin, living under blankets all winter and hoping the space heaters didn’t go out. I saw folks living with sewage backed up in their toilets and massive cockroach infestations that were blamed on them. I saw kids evicted in a routine basis. I remember being with the sheriff eviction squad one day, and we pulled up to this house to do an eviction. And they went in and they go in with armed sheriffs and a bunch of movers, and there were just kids in the house, no adult, just kids. The oldest kid was maybe a teenager, 15, 16. And what had happened was the mom had passed away, and the kids had just gone on living in the house until the sheriff came.

And they evicted the kids, and they put all their stuff on the curb. It was a rainy spring day, and someone called social services. And we were off to the next eviction, and we see over 3 million evictions filed in a normal year in America. And this is something that really hits kids hard. And so, I think that you’re right. You’re right to kind of think about and get us thinking about the depths of poverty. I think that really elevates the stakes of what we’re talking about.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, it’s not just numbers. Those are people. So that’s your first book. You really honed in on evictions, but what led you to write your latest book that just came out, ‘Poverty, by America’?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: I felt convicted. I’ve been spending my adult life researching and reporting on poverty, and I had read a bunch of studies and lived in poor communities and learned a lot from community activists and union reps and service providers. But I just felt like, if someone stopped me on the street and was like, ‘All right, Matt, why is there so much poverty here? And what can we do about it?’ What would be my answer? And so, this book is my answer to that. It is a book I found that I needed to write, just for myself, to get a clear and convincing case to answer those two questions, why so much poverty? And how can we finally end it?

Christin Thieme: And in the book, you call poverty ‘a tight knot of social problems.’ What do you mean by that?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: I mean that it’s not just a matter of addressing income. And I think that any solution to poverty that’s a silver bullet solution should give us a bit of pause. That doesn’t mean poverty abolition is outside of our collective reach. It’s not. It just means that we need to address poverty at the root. And so, that means we don’t just need deeper investments in poverty. We need different policies. We need policies that address all the kind of exploitation, the poor face in the labor market and the housing market and the financial market. And I think we need to rethink our neighborhoods. The country continues to be deeply segregated along race and class, and that is a big part of the solution, striving toward more inclusive broad prosperity.

Christin Thieme: How do you respond to people who say, ‘Well, isn’t it some sort of basically personal failing?’ Or I’ve heard a lot with the pandemic that, ‘Well, people aren’t working, because they can make more staying home.’ What’s your response to that sort of line of thought?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: Well, in the pandemic, it was true that, for a lot of workers who lost their job, the added unemployment benefits were actually more than their usual wages. That’s because the poorest paid workers were the first to lose their jobs. So it wasn’t that the benefit was really generous. It was much more generous than what happened after the Great Recession. But it was a reflection of how poorly paid those workers were to begin with.

We had a natural experiment during COVID, where about half the states took away those benefits and half kept them. So if those benefits were really keeping folks home, we would think that the states that took those benefits away, they get their job numbers up really quickly, right? Unemployment would drop in those states, but that’s not what happened. It was basically a tie between those collection of states that kept the benefits and those that got rid of them. People weren’t staying at home, because they were getting paid. They were staying home for a lot of other reasons, childcare, they’re afraid. They took the COVID to reevaluate their jobs and their choices in the labor market.

And so, I think that this is something we say, but I don’t know if this is something most Americans believe, which is different. I think it’s more like the propaganda of poverty or a myth of poverty, where it’s a response to a problem, but it’s not something we harbor in our heart of hearts.

And survey data bear this out. Most Democrats and most Republicans today tell surveyors that they don’t believe that poverty is a result of moral failing. They believe that it’s a result of structural problems. That’s encouraging, and it suggests that something is crumbling with these old poverty myths that we’ve dealt with for a long time, and now, it’s up to us to create new stories.

Christin Thieme: Is it due to all those structures that we’ve seen the lack of progress? You talk about in your book that, in the last 50 years, we’ve mapped the entire human genome and eradicated smallpox and dropped infant mortality rates and invented the internet, and yet, there hasn’t been any real progress when it comes to poverty. So why not?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: This is a paradox, and I think we really need to embrace the paradox. For some of us embracing this paradox is scary, because the thing that’s happened over the last 50 years is that spending on anti-poverty programs has actually grown. It’s grown by not a little bit, it’s grown by a lot, and yet, poverty still persists. And so, when you point out this paradox, some people think what you’re saying is those programs don’t work. That is not what I’m saying, and that’s not what the research says. There’s a ton of research that shows that things like housing assistance, food stamps, these are lifesavers to a lot of Americans struggling under the poverty line today. We would be a much worse country without them.

So what’s going on? Well, I think you look at the War on Poverty, which we talked about earlier, War on Poverty, Great Society, those were deep investments in the poorest families in the country. They started Head Start, they expanded Medicaid, social security benefits. But those initiatives were also launched during a time when the labor market was delivering, for the average worker. One in three workers belonged to a union. Wages were climbing 2 percent in real terms every single year. So it was kind of like a one-two punch against poverty. But as unions lost power, our jobs got a lot worse. And now, the wages for men, for example, without a college degree, are less than they were 50 years ago.

So when the job market was delivering for the average worker, anti-poverty programs were cures. Today, those programs have turned anti-poverty programs into something like dialysis. They take the sting away from poverty, they deeply matter, but they can’t fix poverty on their own. And so, this is why we need to not only deepen our investments in those programs that work, but also think of ways of expanding worker power, expanding housing choice for low-income families, and ending the unrelenting financial exploitation of the poor done by banks and payday lending industries.

Christin Thieme: Is that what you mean when you write that ‘To understand the causes of poverty, we must look beyond the poor?’ Can you say more about that?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: Yeah. There’s this sentence in the book from the novelist, Tommy Orange, who I love, and this sentence just floored me. He writes, ‘Kids are jumping out of the windows of burning buildings falling to their deaths, and we think that the problem is that they’re jumping.’ And when I read that, I was like, ‘Man, that’s like the American poverty debate.’ For over a hundred years, we’ve focused on the poor. We’ve asked questions about their work ethic and their families and the jumpers. We focused on the jumpers, and we’ve ignored the fire. We’ve ignored folks who lit it, who’s warming their hands by it. And so, it’s important to bear witness to poverty in America, to grasp its nature, and to grasp its depths and its pains and hardships and humiliations.

But the fundamental causes of poverty are not found in the lives of the poor. They’re found elsewhere, and elsewhere means considering the role that exploitation plays in this problem, considering the role that our imbalanced welfare state plays, the fact that we give the most to families that need it the least, and the role that segregation continues to play. And so, yeah, I think that’s right. I think we have to look beyond the poor, which means, for many listeners here, I think, looking at us, taking an evaluation and inventory in our life and how we’re kind of unwitting enemies of the poor sometimes, in ways that we don’t fully realize.

Christin Thieme: What do you mean? Can you share more?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: So many of us consume the cheap goods and services the working poor produce. We often like to talk about shareholder capitalism, as if it’s like 11 guys in pin suits in Manhattan. But half the country’s invested in the stock market. Don’t we benefit when we see our savings going up, even if that requires a kind of human sacrifice? Many of us benefit from the tax breaks that accrue to the top 20 percent of Americans. By my calculations, the average family in the top 20 percent of the income distribution are richest families receive about $35,000 a year from the government in tax breaks.

But our poorest families, the average family in the bottom 20 percent, they receive about $25,000 a year. That’s almost 40 percent less. And many of us benefit from those tax breaks. We get mortgage interest deductions and college savings deductions, but that leaves the country with a lot less to invest in fighting poverty. And then, many of us continue to be segregationists. We build walls around exclusive communities. We concentrate opportunity behind those walls, and that creates neighborhoods, not only of concentrated affluence, but neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, outside of our walls, the side effect of that segregation.

So this can happen intentionally, like when we go to a zoning board meeting and refuse to have affordable housing in our neighborhood, but it can also just happen, just because we’re caught up in these morally fraught relationships in American life. Buying a candy bar, mailing a package, connects ourselves to this. And many of us have become wise to this when it comes to other values, economic justice, racial justice, and I think we should start living our life in more solidarity with poor folks, in ways that are big and small.

Christin Thieme: How do you go about that? I know you wrote an entire book on this, but what is the solution, for the average person who’s listening to this who wants to be better getting involved in helping this topic? What is the next best thing you can do?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: So the book talks about a lot of policies and social movements, and ending poverty is certainly going to need those. But I think the end of poverty will only come when many of us commit ourselves to becoming poverty abolitionists, and this is a political project. But it’s a personal one too. And I think that, for those of us that are down with that project, here are five tangible things that you can do right now.

First, you can flex your influence wherever you are. You’re on a school board, you’ve got a little influence in your faith community, at your job. You can start asking, ‘What are we doing to divest from poverty today?’ I teach it at a university. I should be asking, ‘What’s my endowment invested in? Are we paying our landscapers a fair wage?’ Flex a little bit of influence at the place I have.

Second, we can vote with our wallet, we can shop a bit differently, invest a bit differently. Remember in the 80s, 90s, we started talking about ‘sin stocks.’ We wanted to divest from weapons or oil companies. Well, why not divest from companies that are doing wrong by their workers and stop shopping at those companies too? And why not consult companies, like B Corp or Union Plus, to say, ‘Okay, these are our corporations and businesses that have been identified as places that are really treating their workers with fair wages, good benefits, good power?’ And so, why not support those companies with our money?

Third, let’s talk about taxes differently. And especially those of us that are benefiting from this kind of imbalanced welfare state, let’s not always complain about taxes. And let’s start writing campaigns to our Congress people, for example, asking them to wind down the tax breaks we get, that we do not need, and reallocate the money to fighting poverty.

Fourth, let’s play our role in ending segregation. And that sounds like a result of history and legal structures. And it is, but it’s also a result of a lot of people doing the tedious work of maintaining the wall. So we need to haul our tails to those zoning board meetings too and stand up and be like, ‘Look, I am not going to deny other kids opportunities my kids get living here. Build this thing.’

And then, last, but certainly not least, we can join the anti-poverty movement. And all around the country, there are groups putting in work fighting poverty. The Salvation Army is one of them. And for listeners who want to get further involved, especially politically, I’ve started a website called EndPovertyUSA.org, which highlights and elevates the work of anti-poverty organizations in every state and also working at the federal level.

Christin Thieme: That’s amazing. That’s definitely something to take a look at. That’s five tangible things. Thank you for those. How do we, lastly, all benefit from ending poverty? You said it’s a solvable issue, given us tangible steps to take. What’s sort of your vision of the future, if we are able to do this?

Dr. Matthew Desmond: I love this question so much, because you’re right. The end of poverty is something to stand for, even sacrifice for, not only because poverty is the life killer and the dream killer, but also because the end of poverty means a safer country, a more vibrant country, a country that doesn’t steal so many poets and diplomats and nurses and teachers from us. It means a country where you don’t have to wonder if you’re one car accident or divorce away from real hardship. It’s a country where you don’t have to worry so much about your kids falling all the way to the bottom. It’s a country where you don’t have that gross feeling that you often have when you go out to eat or you go to a hotel and you don’t know if the people cooking your food or cleaning your room are taken care of.

And so, I think this is a country that many of us, even those of us secure in our money, are pining for, longing for. And I think that it’s our job, as poverty abolitionists, to cast this vision too. And it’s like that old line from the book, the ‘Book of Sands,’ where the author writes, ‘If you want your people to build a ship, don’t gather the wood, but make them long for the edge of the sea.’ And I think that part of the job is really making folks long for the end of poverty, for their own benefit, as well as for the benefit of all those kids and parents and workers that are struggling below the line today.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, absolutely. Dr. Desmond, thank you so much for sharing with us today and giving us a vision of what could be.

Dr. Matthew Desmond: No. Thank you. And thank you for all you do.

Additional resources:

- See more of how Dr. Matthew Desmond aims to end poverty at endpovertyUSA.org.

- Read “Poverty, by America” by Dr. Matthew Desmond.

- Read the Pulitzer-prize winning “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City” by Dr. Matthew Desmond.

- It’s because of people like you The Salvation Army can serve more than 24 million Americans in need each year. Your gift helps fight for good all year in your community. It’s an effort to build well-being for all of us, so together we rise—and that good starts with you. Give to spread hope with a donation of funds, goods or time today.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.