Men lead. Women follow. The Bible tells us so.

Or does it?

Is there a divine order when it comes to men and women?

What if so-called “biblical womanhood” isn’t biblical at all but arose from a series of clearly definable historical moments?

What if there is a better way forward for the contemporary church?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr lays out clear evidence that there is in her new book, “The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth.”

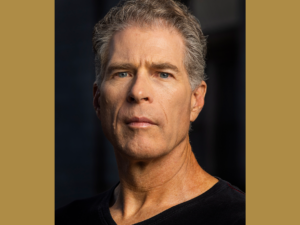

Barr is a professor of history and associate dean of the Graduate School at Baylor University.

She’s been teaching world history for more than two decades while also a pastor’s wife. And as she’ll tell you, there’s more to the story when it comes to those verses on women’s submission and silence.

In this episode, she shares some of the evidence, calls to flip the Christian narrative around patriarchy and offers a vision for a truly biblical view of womanhood.

Show highlights include:

- What is “biblical womanhood.”

- Why Dr. Beth Allison Barr walked out of church one day.

- Why she wrote this book?

- Whether or not there is a biblical divine order.

- Whether or not men and women reflect God in a distinct way.

- Why equal worth manifests in unequal roles.

- How Christian patriarchy mimics the non-Christian world.

- Are things different, better now than in medieval times?

- What it would mean to flip the Christian narrative about patriarchy?

- How the historical evidence about the origins of patriarchy can move the conversation forward.

- The difference between what is descriptive in the Bible and what is prescriptive.

- The attitude of Jesus toward women.

- Why it’s not surprising to see patriarchy in Bible, but what is surprising to see.

- The influence of Paul, and how we’re reading him wrong.

- What Paul is calling us to be.

- What we’re missing in reading 1 Corinthians 14:34-35.

- The role of English Bible translations in our understanding of women’s leadership in the early church.

- As a scholar, professor, wife, mother, follower of Jesus, Dr. Barr shares what the evidence shows her.

- A vision for a theological approach to women in the church with a truly biblical view of womanhood.

- How to examine our biases against women and move toward a truly biblical understanding of womanhood that’s deeper than a surface level agreement of equality.

- One thing you can do today to move toward this vision.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: Dr. Beth Allison Barr, thank you so much for being on the Do Gooders Podcast today and welcome to you.

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Thank you for having me.

Christin Thieme: What is “biblical womanhood?”

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Biblical womanhood is actually pretty easy. It’s the idea that women are divinely ordained to be under the authority of men and mostly focused on home and children. That women are designed for the domestic sphere and men are designed for the public sphere and for leading. That’s pretty much what it is. If you think about 1950s caricatures of the home where the husband is the breadwinner and the wife is the homemaker. That is the idea of biblical womanhood

Christin Thieme: You’ve written this book now, but let’s back up a second. Why did you walk out of church one day?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: I got married to a Southern Baptist pastor 10 days before I started a medieval history and women’s studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. My husband at the same time started his master’s of divinity at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary. From the very beginning, our marriage has been ministry combined with academia and so it’s been a really interesting ride for both of us and we’ve been married now for over 20 years. Along this journey, one of the things that we began to grow more and more uncomfortable with was the rigid gender hierarchies that we began to see being taught in church, being taught from the pulpit.

We started becoming increasingly concerned about these and a few years back, not actually all that long, it was in 2016. We reached a point where we decided that we could no longer sit back and allow these types of gender hierarchies to continue to be taught without us challenging them. Part of this was simply because we saw the damage that it did to teenage girls and boys. My husband was a youth pastor for most of our marriage together. We worried about what we were teaching. What we told boys who were 13, 14, 15 years old, that there was something about them that enabled them to be able to teach scripture whereas women could not.

At our church at the time, women could not teach boys over the age of 13. So we began to worry about the message that this was sending and also the message that it was sending to our teenage girls, that there was something about them that made them unable to be spiritual leaders in the same way as men. That they were divinely called to be mostly wives and mothers. They could do other things, but their primary calling was to home and children. We worried about this because we could not find scriptural justification for it. We also worried about it because we knew that from my experiences as a medieval historian and a women’s historian, I knew that the teachings within the church were really not grounded in the Bible. They were actually grounded in historical circumstances.

We decided, there were a lot of reasons leading up to this, but we decided to challenge this in our church and ask for a woman to be able to teach Sunday School for teenage boys. It was a high school, Sunday School and that led to my husband being fired three weeks later. It was very unexpected for it to happen in that way that quickly. It caused a lot of trauma in our lives, but it also led me to realize that something had to be done. So this book is really born in that moment of trauma in our ministry experience.

Christin Thieme: If we are equal before God, made in his image as male and female, do we then reflect God in a distinct way?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: The question I think here is that if women and men are both in the image of God, yet we are clearly both… women’s bodies are different than men’s bodies. Is there something distinctively different that we should focus on? On the one hand, yes. Obviously, women’s bodies are different from male bodies but at the same time, just because we have those differences in bodies doesn’t mean we have this sameness, this creation in being both in the image of God. I liked Dorothy L. Sayers. She’s one of my favorite authors. She’s one of the first women to get a degree from Oxford in England, in the early 20th Century. She’s a great author, writer and Christian thinker.

She argued more than once. She argued that instead of focusing so much on the distinctiveness between women and men, why don’t we focus instead on how we are both humans created in the image of God and that by focusing so much on our distinctiveness, what it does is it leads us to treat women as being less than human. One of the things that we see throughout history is that women, because they are not the same as men they’re regarded as being deformed men, as being sort of imperfect men and that there is something flawed about them. So they are always sort of othered. In fact, Dorothy L. Sayers, I just love this quote. She says, “Look, when we look at human history,” and she uses the Latin here, she says, “we know that women and men are both homo,” they’re both human.

But yet when we talk about women and men, humanity, homo and [vir], vir is a Latin term for men only, she says that when we talk about homo, we often are referring only to men. When we talk about vir, we’re referring only to men. But when we talk about women, we always make them different. We make them femina. For example, when we talk about jobs, when we talk about political jobs and we talk about people working, et cetera, we often make these masculine terms. You can even think about this.

My daughter, I remember one time she came home and told me how boring she thought history was. That upset me as a historian and I was like, why do you find it boring? She said, “Mom, because women aren’t in history.” It was a really upsetting moment for me because I realized that what she was seeing and what she was reading was… At that time they were studying Wars, they were studying the American Revolution and the Mexican independence, et cetera, and, or Texas, the Mexican war. She wasn’t studying anything about her. She wasn’t seeing women in these stories. She was only seeing the main, talked about men. She didn’t see herself as a part of that story.

I think by focusing so much on the difference between women and men, what we do is we push women out of the story when really, I’ve heard a theologian say before that it’s significant that when God gave us the first creation story in Genesis, he gave it as humanity together. God created humans in his image, God created humans. Then it’s only after that, that we see the distinctiveness that God created, that humans became male and female, but what’s emphasized to us first is that we are human. Human history shows us that whenever we focus on differences between people, it often leads to oppression and slavery. The thought is, why do we keep doing this? What if we focus instead of so much on the difference between women and men, what if we focused on how we are both made in the image of God, on our humanity? I like that emphasis from Dorothy L. Sayer.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, absolutely. As a medieval historian, you’ve taught world history for more than two decades now. In our modern-day post-lib era, where you can find empower women memes and mugs everywhere you look, aren’t things better? Surely things have got to be better than in medieval times, right?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Yeah. I know. That’s such a great question. That’s funny. One of my favorite women’s historians is a woman named Judith Bennett and she’s retired now. She talks about what we call the patriarchal equilibrium and what it is. She described it really well in one of her articles. She said, look, as we look throughout time, as we look throughout history we see that history is kind of like a dance and every era we see, the music changes and the decorations change, the location changes and the way that couples are dancing on the floor changes, but at the same time, it’s always the men who are leading.

So when we think about even our modern history, if we think about the fact that women still make less than men make, in fact, the pay difference between what women make and men make is almost exactly the pay difference between what medieval women made and medieval men made. Over 700 years ago, women’s pay is still less than men’s pay to the same degree. It’s about 75% women make on the dollar for men. That hasn’t really changed very much.

If we look at political offices and who’s in charge, we just now for the very first time got a female vice-president and think about how long the U.S. has been here. In fact, that was another question my daughter asked me. She wanted to know why all of the presidents were men! Why aren’t there any women there? That’s another continuity if we look. Yes, on the one hand, women do have more legal… Ruth Bader Ginsburg has played a big role in helping break down some of the legal barriers for women, but that wasn’t until the 1970s. Yes, we do have more economic power. We do have more legal power than perhaps women did in the past, but if you place it in the overall context, women still have less authority, less power, less opportunities than men do, simply because we are women. That continuity remains the same.

Christin Thieme: You write that the historical evidence about the origins of patriarchy can move the conversation forward. Can you share more about how so?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: With women, one of the things that we have seen really since the 1970s is we have seen an argument between two camps really complementarians, and those are people who argue that women are divinely created to be under the authority of men. Then also the egalitarian camp, which emphasizes the opposite that women and men are created equally in the image of God and equally share in the gifts and callings that God has on our life. Most of the arguments between egalitarians and complementarians boiled down to the exegesis of scripture. Especially the New Testament, especially a handful of verses written by Paul or in the Pauline letters. So those are, if you count on your hands, there’s really only five or six of these verses. The women silent passages, the household codes that say wives submit to your husbands, 1 Corinthians 11:3, that says that the man is the head.

These are really the verses that most of our attention, 90% of our attention has been on. The problem is that we have forgotten somewhere along the way that the reason we interpret these verses the way that we do is because of our historical context, that we are looking at these verses through the eyes of our 20th and 21st century world. Instead of looking at them from the perspective of the 1st century of the Pauline world. When we look at them from the perspective of history, including the broad history of the world, what we see are two things. First of all, we see that our modern argument today is that women being under the authority of men is something that makes Christianity different. It’s something distinctive is what the argument is.

If we actually look at that in the context of human history, what we find is that that’s not distinctive. Humans have been doing that from the very beginning, the oppression of women, the subordination of women, is at human constant, and it is striking to me that if you look at the code of Hammurabi and you look at the Danvers statement it is striking how similar the attitudes are towards women. That makes me think that this is not a Christian response, that this is a secular response. This is a worldly response. World subordinates women, but if we look at the 1st century context of Paul’s words, and especially like the household codes, what we find is that they are actually calling Christians. They’re saying, yes, the world around us is a patriarchal world that subordinates women, but husband, you are called to love your wives as Christ loves the church.

This is radical. Husbands, yes, women are the weaker sex in the context of world history because they have less power and less authority and are more vulnerable. 1 Peter, you are called to regard them as co-heirs with you. It is remarkable what the New Testament does. It rewrites these ideas about patriarchy and emphasizes not that women are different from men, but that women are coheirs with men, that husbands are called to submit to their wives, just as wives are called to submit to their husbands, Ephesians 5:21. So we see this call to really equality towards this emphasis on the sameness, the humanity of women and men. Of course, this culminates in Galatians where Paul says we are all one in Christ. History helps us understand that we have carried the patriarchy of the world to our understanding of the biblical text. If we really want to be like Jesus, then we need to understand that the New Testament is revolutionary towards women.

Christin Thieme: Yeah. Right. I liked that you wrote that there’s a difference between what is descriptive in the Bible and what is prescriptive. That it’s not surprising to see patriarchy in the Bible because it was a patriarchal world, but we have to look at how many passages actually undermine, rather than support that patriarchy. You mentioned Paul being a big part of that. What was his influence here? Are we reading Paul wrong?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: I would say we are definitely reading Paul wrong. The example that I give in the book is 1 Corinthians 14, which is one of the famous women-be-silent chapters where we have Paul where he seems to be saying, women be silent in the churches for this is what we are all supposed to do. If you actually look at that passage what you find is that this is one of many places in Corinthians where we find Paul actually quoting the Corinthian world. There’s several of these places throughout Corinthians. I encourage you to read Lucy Peppiatt who does a really good job talking about these, but if you look, there’s several places where Paul quotes what we call Corinthian slogans. Like, food is not for the body, but the body is for food. Did I say that backwards? I may have said that backwards, but whatever.

We have all these slogans from the Roman world that are actually incorporated into Corinthians. This part in 1 Corinthians 14, where we have Paul suddenly stop when he’s talking about the order of worship in the church and he says women, they say women be silent in the church. Then after that, he actually says, what? There’s this article that we overlook, where he says what? Are you the one? Do you have the authority to say this? It’s like this amazing thing that if you actually think about it, what Paul is doing is he’s quoting the Corinthians. Why do we know this? Because the phrase that he uses there, women be silent, ask your husbands at home. This is a phrase that we find repeated throughout the Roman world. It’s repeated in Roman law, by Roman thinkers, all sorts of folk.

Paul seems to be quoting this Roman sentiment and then saying, “What? Why are you doing that?” Then says no. This order in worship needs to be followed. We need to regard everyone’s voices. We just need to do it in an orderly fashion. That’s what Paul is saying in this chapter, but we have taken his words that… Just think about it, if we have taken Paul’s words, instead of when Paul was telling them not to make women be silent, then what we have done today is the exact opposite of what Paul was calling us to do. We have done what he was condemning the 1st century Corinthians for doing so I do think that Paul has been read out of context. I think that we have focused so much on what we call the plain and literal reading of Scripture, that we forget how important it is to play Scripture within it’s historical context. By forgetting that history, we have missed Paul’s points.

Christin Thieme: I actually have that whole section of your book all marked up because I found it so incredible that the speech that you quoted from, is it Cato the Elder? He almost word for word says what Paul then writes in those verses that women should keep silent in the churches for they’re not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate. Even as the law says, if there’s anything they desired to know, let them ask their husbands at home, pretty shameful for a woman to speak in church. It’s almost directly from the speech that he would have heard at that time. Then, like you said, you tell your students, well, don’t stop reading there, keep going. Of course, the next verse says, “What?!” Like you said.

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Yeah. I mean, it’s amazing. Often in many of our Bible translations that word, what, is not translated that way, it’s changed. What’s interesting in that in other places it’s translated as what. So it’s like this almost intentional change to try to… Because we want to read subordination into the text because that’s what we’ve been doing throughout human history. We’ve been reading subordination, we’ve been practicing patriarchy, so for us, that’s the natural reading, but it’s not the natural reading because that’s what the Bible says. It’s because our human impulse. That’s what is something that we would do not something that God would do.

Christin Thieme: Right. Absolutely. I found that fascinating too, about the translations and how it can completely change our understanding of the passage, obviously. So what translation do you recommend we read?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: I get that question from people all the time. They’re like, well, what Bible should I read now? Here’s generally what I say. I say, number one. If you look at all of the Bible translations in general, statistically there’s very little difference between them. The story of God’s Word, the story of the message of Jesus comes loud and clear through almost any of the Bible translations. There’s only a few that have been really so prepped that the message [inaudible], but those aren’t really Christian Bibles. So in general, you can use almost any Bible. My advice is to make sure you know who translated your Bible and why they translated it. That is so critical to understanding. We forget that the Bible is translated by humans.

I think the English Bible is often… Obviously, some of them are the most pervasive translations, but we don’t realize how bad English is for translating biblical languages. English is a difficult language and it does not translate from ancient language as well. There have to be lots of decisions made about how to frame the texts and the translators, who make those decisions are all carrying to the texts, their own ideas. Even if they try to be objective, we all know that humans can never be objective. We’re just not good at that. We are always subjective. They’re always going to interpret it through their own biases.

For example, the ESV is an example that I gave and the English Standard Version was the translators that can post it were battling what they saw as a feminist overreach and the today’s New International Version with the gender-inclusive language. They were trying to combat that gender-inclusive language as well as to make sure that what they consider to be God-ordained gender roles, women under the authority of men. They wanted to emphasize that. If you look in the ESV you’ll see things like Junia, who is a woman in Romans 16, she was always a woman until after the reformation, when Martin Luther translated her as a man because he didn’t think a woman could be an apostle. Most people ignored Martin Luther’s change here, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, people picked it up again and began translating Junia as Junias, only for the reason that they did not think a woman could be an apostle. That was their logic behind it. So they changed her to a man.

The ESV, they say Junias prominent among the apostles, then there’s a footnote below that says some people have said, this is Junia. Well, actually it’s the opposite. She is Junias and then a footnote down below that says some people in the very modern history have decided to try to translate her name as masculine, even though there’s no evidence for it. This is one of the ways that I think that translation can really skew our understanding. Pay attention to what translations you’re using. I like the NRSV. I use the NRSV a lot. I use the NIV, I really like the NIV. I grew up on the NIV, so it’s familiar and comfortable to me. I like the TNIV. I’m a medieval scholar so I read the Wycliffe Bible and Middle English versions of the Bible and the 16, 11 KJV. I use all of those quite a bit. So I would say use more than one Bible and just pay attention to who translated it and understand what they were doing with the translation.

Christin Thieme: Even look beyond the actual words. You talk about how Paul, you make the very strong case that he was refuting Roman sources in his writing, but even if that’s not the case, there’s more to the story you say; look at how he uses and lets women speak through his letters.

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: That’s the thing too, is that while I’m convinced as a historian, that from the evidence that what Paul is doing there, in 1 Corinthians 14 is not telling that he’s quoting the Roman world. It’s really hard for me to see that in any other way, but I could be wrong. As a scholar, we should always be willing to admit we’re wrong. What if I’m wrong? What if that’s not what Paul is doing? What if Paul is actually saying that? Well, then what I know is that Paul cannot be telling women to be quiet and only ask their husbands at home, he must be saying it for a specific reason, combating something specifically going on in that church that we simply don’t know about anymore because Paul doesn’t tell women to be silent.

We know that he allows women to seek, teach and lead in the early church. He gave Romans the letter of all learners, some scholars have called it. He gave that to a woman, Phoebe, a deacon to deliver, which means that if she was the one delivering it, she was the one reading it. She was the one who preached Romans first. If you think about that, it’s just mind-blowing to think that how could Paul be telling women to be silent, not to speak in church, if he’s giving Romans to a woman who becomes the first preacher of Romans.

Clearly, Paul is not giving a blanket; no order, that no women can preach, teach or lead and that they always have to be under the authority of men because he didn’t regard women that way. He had other women in the church who served as house church leaders who served as deacons, like Phoebe, who served as apostles like Junia. These women worked alongside Paul, which means that he allowed and accepted women as leaders in the early church.

Christin Thieme: Absolutely. I like how you wrote, I’m going to read it a little quote from you on this topic. You said, “The problem wasn’t a lack of biblical and historical evidence for women in leadership. Mary Magdalene carried the news of the gospel to the disbelieving disciples. In a world that didn’t accept the word of a woman as a valid witness, Jesus chose women as his witnesses for resurrection. In a world that gave husbands power over the very lives of their wives, Paul told husbands to do the opposite, to give up their lives for their wives. In a world that saw women as biologically deformed men, monstrous even, Paul declared that men were just like women in Christ.” You’re a scholar, a professor, a wife, a mother, a follower of Jesus. You’ve studied this in-depth. What is a truly biblical view of womanhood?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Yeah, well, I think a truly biblical view of womanhood is that God calls women to do all sorts of things and that God doesn’t and never has limited women to only one type of role. God has used women as wives and mothers, but God has also used women in other roles as well. He’s used them as prophets. He’s used them as teachers, as preachers. He’s used them as bringing salvation. I mean, if you think about Rahab, who’s the rescuer of the Israelites and helped make sure that they actually escape Jericho. He has used women throughout the Bible.

He calls them, if you think about Mary, Mary is given this amazing role. I think it’s no accident that Jesus came in the body of a man, but he came through the body of a woman. It’s like, God was making a point to us that one sex is not more important than the other, that we are both in the image of God that we are both made as humans and God uses women and men together and uses them in all sorts of different roles. That’s the thing about it. If we think about God has never been limited and He never limits people. It’s people that keep limiting people and that’s what’s always surprising to me. Why do we draw limits that God never did?

Why do we say women can’t preach when God called Deborah? Why do we say that only men can serve at the altar when Jesus came through the body of a woman. Why do we say a woman’s body, that there’s something about it that makes it unable to be as spiritually pure as men, when, as I said, Jesus came in the body of a woman. Why do we say that there’s something about women that their spiritual understanding and discernment needs to be under the authority of men, when Jesus listened to women over men.

You think about the woman of Canaan in Matthew 15, where the disciples are telling her to be quiet and telling Jesus not to listen to her and Jesus doesn’t. He actually engages with her directly in a conversation. Then he believes her and recognizes her faith and her daughter is healed because of that encounter. Jesus says, “Woman, you are of great faith.” He doesn’t say that to the disciples. He tells them over and over again, how often they are not of faith.

It’s just amazing to me that we don’t realize how much God is showing us that women can do everything in these ways that men do. It doesn’t mean that women are the same as men, just because women can preach, teach and lead like men doesn’t mean that they suddenly are becoming men. I don’t really understand that argument. It just means that God calls both women and men. That to me is absolutely beautiful. He calls us both to lead. He calls us both to be stewards of this earth and he calls us both to work together. So the vision of God is so much bigger than we have allowed it to be. So I just wish a biblical view of women is: let God use women the way that he calls them and don’t try to tell them what they can or cannot do.

I think about Piper and Grudem’s list. Every time I read it, it’s just crazy to me, about trying to figure out if a woman… They argue that a woman shouldn’t have personal control or authority over a man. They go through and try to figure out what jobs a woman can have, where she doesn’t have personal direct authority over a man. As a historian, it’s crazy because almost all of those jobs are only applicable to the modern Western world. They only apply to a very small portion of the world’s population and the world’s history. It shows us how arbitrary and how inconsistent these things are whereas the consistent message in the Bible is that women are used by God, just as men are used by God. So let God use women. That’s biblical womanhood. Yeah.

Christin Thieme: Let’s say that we reach an agreement on an egalitarian approach to women in the church. What’s your advice though, for how to practically examine some of the biases that might be there? Or how do we move beyond maybe a surface-level agreement of this equality? How do we get deeper?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: I was actually just writing a piece about that, a piece that’s late that I should have turned in before [inaudible]. That’s my life right now. I think part of it, our superficiality has to do with our unfamiliarity. We have made it so difficult for women to serve in these positions and shut them out of leadership that now we live in this world where it’s a strange space to hear a woman speak authoritatively, to hear a woman teach, to hear a woman preach. It seems to me that… It’s what I tell my kids, if you want to get good at something, you’ve got to practice it. So I think we’ve got to start putting women in these spaces and letting people hear women and letting people realize that when God calls a woman to preach, that the wisdom that she has is just as important as the wisdom that a man has and that women can often see things differently than men do.

This creates a better, more well-rounded understanding of what God is trying to teach us. I think we can move beyond superficiality by working to make sure we get women in these spaces. It’s always so frustrating when you see churches that say, “Oh yes, we support women in ministry. We support women doing these things,” but then they don’t hire women. Then they don’t appoint women as elders or deacons. They don’t have women teaching adult classes. What we get is still this continued superficiality, this lip service without actually recognizing and allowing women to use their gifts in the way God has given them. I think the only way to make this normative is to practice it.

I know part of the modern argument is that, well, this has never been done, but if you actually look back throughout church history, in the medieval world, women religious examples were everywhere. Medieval people had examples of both women and men all around them serving God. Now, patriarchy still existed in the medieval world so it wasn’t a golden age. Still, I think in this modern world, we have just gotten so unfamiliar with women serving that we’ve forgotten that women can do it. I think we’ve just got to practice what we preach and within a couple of generations, it will be normal.

Christin Thieme: Last question, what’s one thing, something tangible that we can do today to start moving toward this vision of a true biblical womanhood?

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Oh, read history of women. If we look back through, women have been fighting this. I’m not claiming that women in the past had what we call today a feminist consciousness, but there are women throughout the past that have recognized that there are problems with these structures that women are shut out of leadership. One of the things that they continuously pointed back to I’m thinking of Christine de Pizan and the medieval world and in the 15th Century. She sees all of this misogyny in her age and all of these horrible ideas about women. So she combats it by writing a book called The Book of The City of Ladies, where she says, what you are learning about women is not true. Women have always been leaders and have been significant figures in history and church history. We need to know about them. We need to learn about them.

I have found, as being an evangelical and growing up in the church, I find there is a huge disconnect between what we learn in Sunday School, between the books we read about church history, through what we hear preached from this pulpit, we don’t hear about women. We do not hear about women in the same ways that we hear about men. So simply by actually telling the truth about history, showing the women who were important figures in the church, instead of telling the reformation only from the perspective of Martin Luther and John Calvin, why don’t we talk about all those preaching women? Why don’t we talk about Katharina Zell? Why don’t we pull in these important female voices and make them essentially just as important as the male voices that we talk about.

I think just even doing that, just recognizing and restoring women to the role that they’ve always had in history and helping women understand that, can move a long way. Like I think about my daughter, again, saying that history is boring because women are not in it. What if women saw themselves in the church as teachers and leaders, they would much more be willing and understand that they can be called to those roles if they saw in the past how women have been in these roles. That’s one way is just, let’s include women in what we teach, preach about in the church.

Christin Thieme: There you have it. If you need a place to start, I can definitely recommend to you, The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth by Dr. Beth Allison Barr. Dr. Barr, thank you so much for sharing today and for giving us this incredible book to learn from.

Dr. Beth Allison Barr: Thank you so much for having me. This has been fun.

Additional resources:

- Read “The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth” (Brazos Press, 2021).

- Connect with Dr. Beth Allison Barr.

- Find a group study guide for Dr. Beth Allison Barr’s book.

- Get inside the Caring Magazine Scripture Study Collection and find a suite of free, downloadable Bible studies to guide you through topics from New Beginnings Through Forgiveness, to Understanding our Imago Dei or Life Hacks From David.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.