There’s a reason one story can stop you in your tracks.

Not a statistic. Not a headline. But a single voice. A single life.

You might be scrolling, half-listening, distracted—until suddenly, something shifts. Your chest tightens. Your attention sharpens. You lean in.

You don’t just hear the story. You feel it.

And in that moment, something happens inside your body before you ever make a decision.

Your brain releases chemicals linked to empathy. To trust. To connection.

You begin to care—not because you were told to, but because you’re wired to.

This is why stories matter.

Not because they’re persuasive in the abstract—but because they invite us into relationship.

They help us see another person not as a problem to solve, but as a human to understand.

Neuroscience tells us that when we hear a story about someone else’s experience, our brains often respond as if it were happening to us. We feel what they feel. We imagine what it’s like to stand where they stand.

And when empathy is activated, generosity often follows.

Not out of guilt. Not out of pressure. But out of connection.

This season, we’re sharing stories of joy—stories of help received and hope passed on.

But underneath every one of those stories is something deeper: the science of why stories move us at all.

And so today, we’re joined by someone who studies this very phenomenon.

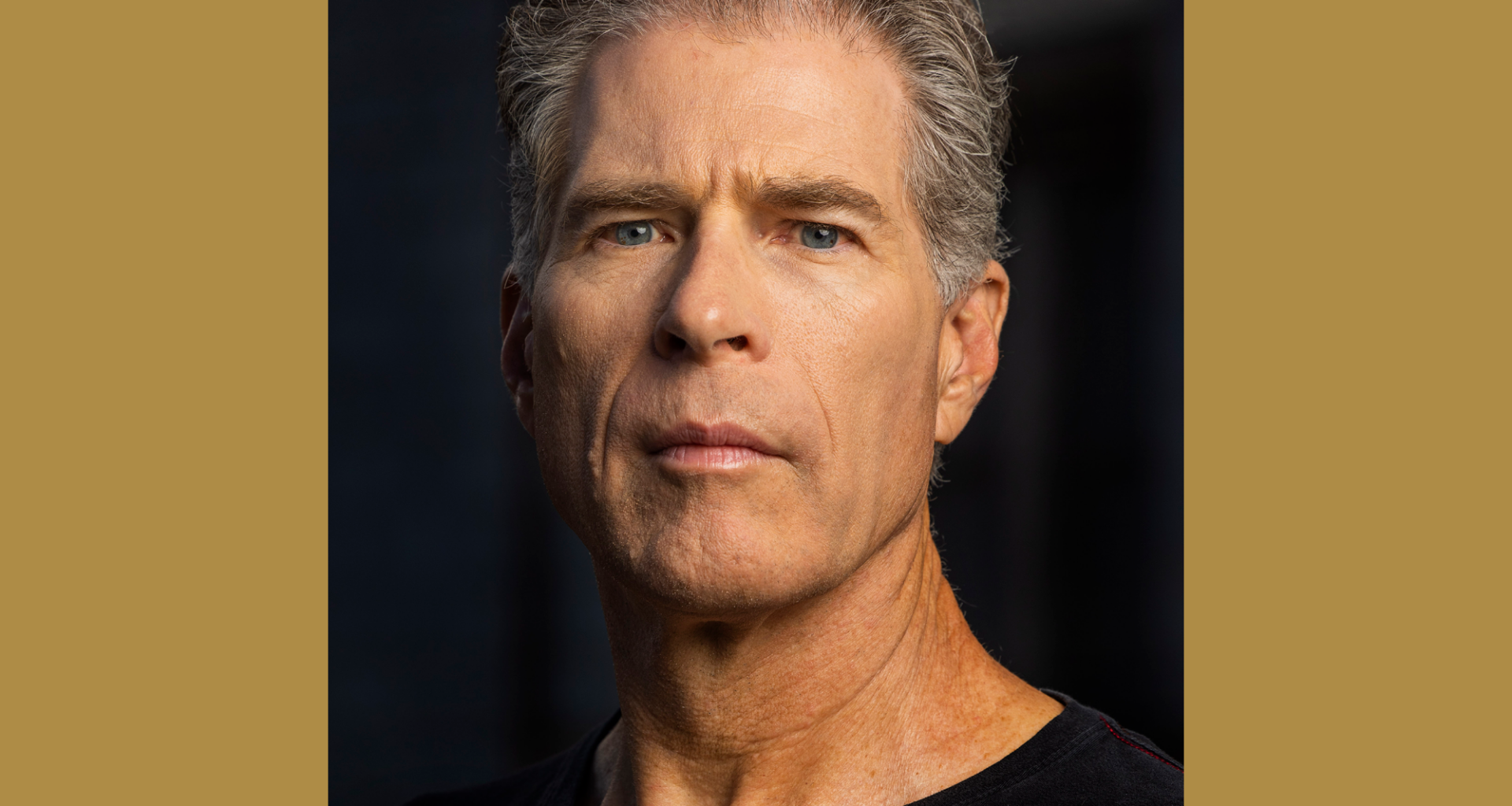

Dr. Paul Zak is a neuroscientist known for his research on oxytocin—the hormone linked to trust, empathy and generosity—and how storytelling activates it.

His work helps explain why hearing one story can change how we see the world…and why stories don’t just inspire us—they shape how we show up for others.

Show highlights include:

- What actually happens in the brain when we hear a story that moves us—and why oxytocin plays a central role in empathy, trust and generosity.

- Why personal, human-scale stories are far more effective than statistics or data at inspiring action.

- The science behind “immersion”—and how narrative tension and authentic emotion shape what we remember and act on.

- How empathy doesn’t diminish joy, but multiplies it—making joy something we share, not just feel.

- Why giving, volunteering and helping others leads to lower stress, better health and longer life.

- How introverts can intentionally build meaningful community without changing who they are.

- Why stories of transformation—especially from crisis to hope—invite listeners to participate, not just observe.

- What makes a story truly effective in motivating action, and why a clear invitation (“the ask”) matters.

- Why every person’s story matters—and how sharing our stories strengthens connection and belonging.

Listen and subscribe to The Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Christin Thieme: You’ve said that stories can change behavior. What actually happens in the brain when we hear a story that moves us?

Dr. Paul Zak: So I’m going to go back one step. I’ve spent my entire career developing knowledge and technology so people can live happier, healthier, and longer lives. And one of the things we looked at in early two thousands before anyone did really was the role of this neurochemical oxytocin.

So many people have heard of it now, primarily based on the early work I did, and others have done a lot more after that where we looked at why people are so nice to each other. The bad behavior gets all the press, but the good behavior is like the air around us. We don’t really notice it.

And so I start thinking about where’s this good behavior come from? And if we know the mechanisms that produce good behavior, we know what promotes or inhibits it. And bringing this back to happiness, we know that people who are pro-social, who connect to others who care for others who are generous, who give to charity, who volunteer, they actually are happier individuals and they live longer lives.

So that pro-social behaviors, understanding that fits right into my 30 year research program. And we ran these experiments measuring blood, measuring changes in oxytocin and some other related neurochemicals that strongly predicted the degree to which people would help other people even when no one was looking anonymously. So these experiments were very well designed and laboratory based, but they don’t scale.

So the question we asked, and I’ll answer your question now, is how do we scale pro-social behaviors, which are again so good for the individual who’s a giver and actually so good for the receiver as well physiologically, and I can tell you more about what good means physiologically in a minute, but we started looking at story as a way to do that. And Christin, I’m a behavioral neuroscientist. I don’t want to depend on what people tell me they like or they feel good because that doesn’t predict hit movies or hit books or anything.

We just don’t know because most of our brain activity is unconscious. So we measure brain activity. When we showed people a small public service announcement, like a 90 second video, PSA took blood before and after and then compared the activity of people who donated to the PSA because we paid them, right? We’re torturing them. So we gave them 40 bucks and they got prompt after the second blood draw by computer saying, you’re in 40 bucks, would you like to donate some to a charity associated with this? Cause we found that two things strongly predicted if people would donate. The first is if you are attentive to the experience, that’s first, right? So we’re doing all kinds of things. If I’m distracted and not looking at you, it’s not going to be a nice experience for you or for me. So first is thing’s got to get my attention.

It’s table stakes. And that’s usually where so many of the metrics we use stop eyeballs time. But tension doesn’t mean actually care about this. So that attention associated with the action of another neurochemical dopamine, if that attention is followed by an emotional response we call emotional resonance, which is associated with oxytocin release, then people readily will donate to charity even after they’ve been tortured and even after they have money in their pockets.

And the sort of classical view in economics is money’s good, I just keep money all the time. But what we find in human beings is that we have very specific neuroanatomists that make us much more sensitive to the needs and the suffering of others. And by giving to others, not did we help that other person, but we get that benefit ourselves.

Christin Thieme: So that PSA—tell us why that single personal story has more of an impact than hearing about the statistics and the data around whatever the issue is.

Dr. Paul Zak: Right? So we’ve run this for 20 years, many, many, many ways. And it’s like when you see the data line up the scales 12 in your eyes and you go, oh, of course this is English 101 in college. And what we found is that human scale stories, personal stories about an individual, often a named individual who is going through some kind of crisis and needs help that has a narrative arc. So not a flat story, we looked at those, but a narrative arc where there’s a crisis, there’s an opportunity to do something heroic, there’s a chance to have a sense of growth and change and transition and transformation.

Those kinds of classic story structures sustain this network in the brain that values social emotional experiences. So in all this research, we identified a network called immersion, which is how the brain values social emotional experiences and what is valued is what is acted on and remembered.

So what we found is that the higher the neurological immersion, which is the electrical signals associated with dopamine and oxytocin, neurochemicals induce electrical activity that we can measure. So we have technology where we can measure this now at scale anywhere by applying algorithms, an app we built to smart watches and fitness wearables.

So we’ve done this for thousands of thousands of people outside the laboratory where people really live and we find that human scale story that generates authentic emotions. It could be a fictional story like people cry at movies all the time, not me because I’m way too much, but I’ve heard that people occasionally cry at movies. Those are often fictional stories.

So it doesn’t have to be true story or it could be a synthesis of loss of stories of, for example, people were helped by the Salvation Army. It could be a synthesis of those stories. You don’t want to identify a particular individual because of anonymity reasons. So it could be a synthetic story, but it’s got to generate that authentic emotional response. Right? Here was an individual who was having a crisis, who was suffering, and here’s what we did or someone did to help alleviate that suffering and allow someone to live a better, healthier, happier life.

Christin Thieme: Can you explain oxytocin in simple terms and why it matters for our human connection?

Dr. Paul Zak: Yeah. So oxytocin is one of the 200 neurochemicals active in the brain. It interacts with lots of other neurochemicals, as I said earlier, including dopamine and a bunch of others. And what’s unique about humans or one of the things that’s unique about humans neuroanatomically, is that we have many more receptors in the brain for oxytocin than do other mammals. So oxytocin is classically associated with live birth milk, let down for breastfeeding and attachment to offspring. And in some 5 percent of the mammals that pair bond, including humans, that is pair bond means males and females generally stay together during offspring. So offspring and those mammals, including humans, are more successful. They’re more likely to survive and reproduce themselves if they have two parents involved. And so therefore, we have this chemical that allows us to strongly be connected to other people, by the way, including our friends, our pets.

If you had a dog, you love your dog. I mean, 99 percent of dog owners love their dogs. So that’s a real thing. And we’ve actually done research on dog-human and cat-human relationships. And indeed it’s the same mechanism we find in friendships and romantic relationships and even care for strangers. This kind of pro-social behavior I talked about.

So this is a really powerful chemical. It does a couple of things that I think tell us why connecting to others and in particular volunteering and donating money to charity are so important to human beings. One is it is a chemical that increases our sense of empathy. So if we think about all the amazing things human beings have done, send men to the moon, that’s crazy. That’s just crazy talk.

Chimpanzees are not even close to us or build giant buildings or subway, I don’t know, cars, chimps, which we share 98 percent of our DNA with chimps, they’re not doing anything close. They have little primitive tools, that’s about it. And they have culture, but that’s it. So that sense of empathy.

So we have other mechanisms of the brain that allow me to forecast cognitively what you’re likely to do. If I were Christin in this situation, what would I do that is useful? But empathy gives me, oh, this is why Christin cares about this thing. This is why it’s important to her. That allows us to be much more effective cooperative creatures. And it’s totally natural for humans to be put in a big building. We call an office and work together with strangers. Totally natural chimps don’t do this, monkeys don’t do this, gorillas don’t do this. So it’s totally natural for us to be around strangers all the time. It’s why we like living in big cities like New York and San Francisco and Chicago. So that’s a natural thing for us.

It’s not unnatural. So that empathy, that share of sharing of emotions, which is what empathy is, makes us such more valuable creatures. It also tells us why we connect to people at a distance like crying at movies or watching an ad for The Salvation Army and saying, oh, I want to help this other person. I feel empathy for that person.

A couple of things oxytocin does once it reduces our physiologic stress. It feels good to be connected to community. And that’s what we find in people with a history of volunteering, is that they actually release more oxytocin when given a chance to help another person because of that they have more friends, their physiologic stress is lower, their cardiovascular health is better. And who’s more interesting to be around selfish people that are just trying to grab and grab and grab or helping people who care about others.

And the last thing oxytocin does, which is very interesting and consistent with this conversation, is it through that stress response improves the immune system. So in the post-COVID world, it’s like, oh my god, people viruses. Actually, it turns out that people with more friends get sick less often. Why is that? Because they’re more connected to community, they have better functioning immune systems. So we’re around viruses and bacteria all the time a hundred percent of the time. Even at home, you’re not away from these things. But if you have a healthy immune system, then you can resist getting sick and the immune system’s working to keep you healthy just gets overwhelmed sometimes. So to me, if you want to live a longer, healthier, healthier life, the focus of all of my work, remember, one thing you want to do is to connect to others, to help others.

You can do that effectively by telling a story or by communicating why this is important to you. And so bring a friend along, right? If you want to get involved in your community. I moved a couple years ago and I met all kinds of people in the movie place. I live, first of all, I have a dog. And so dog walkers are safe. You can meet everybody. But I made a point to get involved in my community, to get to know people, to share phone numbers, to go grab a coffee. That’s the healthy thing to do.

And by the way, you can’t tell because I’m talking your ear off now, but I’m a big introvert. I’m out of the basement lab and they’re letting me see sunlight. This is a big news today for me, but because I know that I’m introverted and I don’t need as much social interaction, I make sure I give myself a prescription for that social interaction every day.

By the way, the UK National Health Service, I’m making a joke, but actually they have this called social prescriptions for people who particularly have some mental health challenges. They’re anxious, they’re depressed, they actually, if the physician gives them a prescription to spend a couple hours week at a community center helping other people. Oh gosh, doesn’t that sound consistent with the whole story I’ve been telling you? This is all science-based, not my opinion. It’s all published research and people can go to Google Scholar and pull up all that research and read it.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, that’s an interesting point about being an introvert because I think a lot of times people think about people who volunteer, who are connected to their community and so on, are the very extroverted out there, talkative people. So can you just share a little bit about how you intentionally go about that? I mean, you say you give yourself a prescription, what do you mean?

Dr. Paul Zak: That’s a great question. So because I’m inclined not to have as much social interaction as people extroverted who just want to interact more, I make sure that I sort of schedule that in. So I will schedule happy hours, I’ll schedule activities. And a couple years ago, Christin, to be honest, I would like, why am I the schedule for all my friends? Why isn’t someone else schedule these? And then the more I thought about it, I travel a lot, so I’m probably out of two weeks out of the month I’m out.

So I’m more complicated than everybody else in terms of timing. And then I also thought, these are my dearest friends, these are people I love. Why don’t I schedule? That’s fine. I can be the scheduler. Why am I feeling bad about that? It’s wonderful. I schedule, they show up. What could be better than that?

So I just schedule it so that I ensure that, and I think for listeners who are introverted or who may be feeling blue, sometimes the more you engage with others, the easier it gets. So our brains are very adaptive. I met my wife on an airplane in Cincinnati, a place neither of us lived because she ordered a special meal and I did too. And I tapped her on the the seat in front of me, by the way, and I tapped her on the shoulder and chatted with her. And 30 years later and two kids, it worked out. Talking to people is fine. I didn’t stalk her. I just chatted with her and we ended up living 20 minutes from each other in the Philadelphia area. And there you go. So I think we have to kind of force ourselves to do this. I left our own experiments on myself.

So some years ago I decided I would talk to people on elevators. It’s super weird to me that we’re in this box always the place. We never talk the people. So my experience is about half the people I say hi to an elevator are kind of freaked out, which somehow makes me happy. Come on, we’re just another human in the box. And the other half you have this wonderful 20 or 30 second conversation with them, like, oh, in a hotel or a conference center saying, oh, where are you coming in from? You got luggage? Oh yeah, I was talking to these people. They were speaking in Dutch, which I sort of understood was Dutch because I speak a little German and they go, that sounds like you guys are speaking Dutch. They’re like, oh yeah, we just came from Amsterdam. We’re here for the conference. I’m like, oh, I was in Amsterdam two weeks ago. And you get to know them. So what I do is I just keep that muscle, that engagement muscle nice and worked out. So it’s just comfortable to meet folks. And by the way, it drives my young adult children crazy that I’m talking to the waitress. It also makes me happy. Yeah.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, there you go. So take some intentionality then.

Dr. Paul Zak: Put yourself in that situation. I think I talked about volunteering very quickly earlier, but I think one of the great things that Salvation Army does is give people a chance to volunteer. And so donating money, awesome, that’s great. And you’ll get that. We call it warm glow. You get that warm glow, that good feeling. But physically being with other people and helping someone out is really part of our human nature. It’s not an oddball thing. There’s not weirdos. This is really, really important. And the more you do it, the more value you get from it, the easier it becomes. So I think by providing opportunities to actually volunteer and help others, you are actually helping people live happier lives. So I’m a fan.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, absolutely. So we’ve talked about with hearing a story, we released neurochemicals that help us to feel good, to get involved, to want to be more connected from a neuroscience perspective, why are we so responsive to narrative, to story?

Dr. Paul Zak: Yeah, that’s another great question. So the brain is one of the most energy hungry organs in the body. It takes about 20 percent of your calories to run your brain, and it’s about 3 percent of body weight. So we evolved to basically modulate that high energy overhead by just chilling out. Most of the time, the brain’s in idle mode.

So we find in this network, I’ve called immersion, that value social emotional experiences in the brain is that there are certain stimuli that will induce this kind of peak immersion experience. I’m using this again as immersion with a capitalize a term of art. I don’t mean this casually, I mean it specifically as this one second frequency combination of electrical signals that we can pick up with an app. So technology that’s being used around the world every day by companies, by individuals to improve their emotional health.

So I can tell you more about that later, but I mean this again, a measurable physiologic response. So when I see this big peak in immersion, it’s like the holy crap kind of response in your brain. Again, this is unconscious. You don’t know this consciously. It’s like, oh, this is really, really valuable to me.

So we looked at a variety of different stimuli. I mean at this point, thousands and measured their neurologic immersion. We find that those factors that sustain our attention easy to do. I just clap my hands. I can get your attention, right? That doesn’t mean it’s very meaningful, it just means I got your attention and I have this growing tension. So in the sort of classic narrative arc, again from English 1 0 1, I have this increasing tension in the story. So as gregarious social creatures, we are fascinated by the other humans because we’re all kind of connected physiologically.

And I’ll tell you about that physiologic connection in a moment, if you will, if you’ll wait a second. But we are not running out of stories, movies, novels, they’re all about people. Even what was that robot movie? Wally? Wally, we just anthropomorphize Wally. He’s a robot. But we treat him because he moves and he seems to have emotions. We treat it as if it’s a human. So we’re fascinated by that. So if I can structure that story in the ineffective way with increasing tension and authentic emotion, that I’m likely to get this big peak in immersion. And that tells my brain that this is important to me.

And so I’ll just give you a concrete example. So I wrote a book in 2022 called Immersion so people can find it. It’s super cheap now because it’s older. But we did some work with the Humane Society of the United States, whose donations have been flat for many years. This is all in the book. And what we found is that they were putting these stories out on YouTube that would last three or four or five minutes because YouTube basically doesn’t cost you anything to have a longer story, sad puppies and sad kitties and rabbits or whatever.

Christin Thieme: So sad.

Dr. Paul Zak: People tuned out, physiologically tuned out after about a minute. So I get it as the Humane Society, they’re helping these poor, helpless animals. Great. The longer it went, people were so tuned out by the time they had the call to action at the end, they had dissipated all that tension, all that emotional immersion component of the story. And the call to action was very weak. So we advised them was make a nice 30- or 60-second story, put it on YouTube, it’s ready for TV as well. If you want to run it on tv, run the standard commercial length story. Hit me hard, hit me fast, give me a reason to care, and then ask me to do something. So I think sometimes I haven’t looked at Salvation Army advertising in a long time, but sometimes we tell the story, but then we don’t make the request.

So think of immersion as tension in your brain, and I want to dissipate that tension by doing something. So just have that ask I think is very important. When I’ve got that tension. Again, people have big brains. You’re not brainwashing anybody. You can say no if you want to. So for example, we’ve studied Super Bowl ads because that’s sort of the apotheosis of advertising. So we’ve done this for many, many years, and by the way, most of ’em have no effect on sales, 90 percent of ’em. So the question is, what do you do with these ads? So they all go on YouTube. What drives me crazy is that even for the really good ads, those 10 percent that actually move the markets, you don’t pay some $15 an hour intern on YouTube to put a hot link to a call to action. So for you guys, I hope when you advertise on YouTube, if you do, there’s a link there, donate now, volunteer.

Now you’ve captured me and my brain’s going to go back to idle mode. It’s going to chill out after this experience. You’ve got to have that call to action. And by the way, for all the people listening, this applies to asking out that cute girl or guy making a sale. If you’re in the sales, I mean, we’re all in the sales business at some level. So once you’ve told a good story, once you’ve connected to them, ask them if they like to do something, they can say, no, you’re not being overly aggressive. But there’s a short window in which the brain is really going to be investing a lot of metabolic energy to process what you are trying to convey to this other person. And that’s when you want to actually make the ask.

Christin Thieme: So good for our organizational communication and individual. How does empathy influence our own joy?

Dr. Paul Zak: What a good question too. It seems weird because empathy seems like sort of a negative emotion in a way. If I’m empathic, if I’m sharing your emotions and you’re sad, how can that affect my joy? But it turns out that our emotional states, our physiologic states are contagious. So if you’re in pain, I’m going to feel that pain. And that’s one reason people are motivated to help others. If that convey through a story by looking at you, by talking to you that you’re suffering, most healthy individuals would want to help. You don’t even have to ask. They’ll see it, they’ll understand it. The same thing happens on the positive quadrant. If you’re experiencing joy, I’m also going to experience your joy. I get to share that joy. So I’ll give you a concrete example of how powerful these effects are. Again, we’ve made software that companies use individuals use all the time to create amazing experiences.

Customer experiences quantifies neurologically, the value of these experiences, and a luxury retailer who I won’t mention, but people would know, wants to know why 20percent of their sales associates sell 80percent of their merchandise. Now, if you’re walking into a very high end luxury clothing store, so we get these data by applying algorithms to smart watches and fitness wearables, we can’t ask you to, Hey, customer, put on this Apple watch. We want to measure your brain. It would be too weird. But we know because of the contagion effect. So we had this company had salespeople have a smart watch, use our app to capture neurologic immersion, and they could predict with 80percent accuracy, which customers bought just based on the brain response of the individual sales associate.

So that’s really interesting. And in fact, the higher their neurologic immersion of the sales associate, the more money that the customer spent and the maximum spend was over $2,500. It’s like this is real money. This is not 10 bucks. So it means that we are sharing emotions all the time with other people. And so one thing that we can do to be live happier lives and be more connected to human beings, which we need to thrive, we need to be connected to others, is to be emotionally open. And so a lot of the work I’m doing now is creating these technologies that allow us to measure the strength of our social connection so we can train ourselves just like talking in the elevator to be more emotionally open, more willing to share our emotional states, and that brings people towards us and helps us connect and again, live these longer, happier lives.

Christin Thieme: I think that being emotionally open is a key thing for us to realize. I mean, we’re talking a lot about story and about sharing story, even sharing our own story and why that matters and connects you to other people. So for somebody listening who maybe wonders whether their story matters, why anybody would be interested in hearing it, what would you say to that?

Dr. Paul Zak: I think it’s a great question. The data suggests if you have three close friends that know your story, you’re actually good for your whole life. I call these 3 a.m. friends. Some of you could call it 3 a.m. if you really had to like you’re having a crisis. So how do I develop those 3 a.m. stories? When is investing time in their relationship? And that investment needs to be pro-social, right? I need to be giving to that person not always giving. They should give back to me. It should be reciprocal. It doesn’t have to be perfectly reciprocal. Like me being the organizer of my friend group, I’m okay. I’m an organized person. I’m happy to do it. So you’ve got to spend time with them. Now, what happens when you spend time at happy hour over coffee on a trip? Well, you tell stories about your life. You’ll tell stories about things that you remember that this scenery in the car reminded you of.

And so by sharing personal stories that have authentic emotions in them, we really connect to other people more effectively for people who are struggling. There are some really good apps now as well that will prompt you using AI to tell your story. For example, for older individuals who want to share their story with their family members, and it feels kind of sometimes a little bit awkward to say, Hey, grandkids, I want to tell you about my experience in the war, my experience growing up in Hungary, or whatever that is. So one of those is called Remento, which I think is very low cost. I don’t really remember the price, but it basically just prompt you on things that go through history and we’ll learn about you, and then you can just audio record your stories or video and then you’ve saved that. So I think we all have stories. We’re all important. Every individual is special. And that specialness is not only our current state, but our histories.

Christin Thieme: Yeah, your most recent book is called, “The Little Book of Happiness.” Can you talk a little bit about why you titled it that and why how we approach living a life of happiness?

Dr. Paul Zak: Thank you. Yeah. After 30 years, you think I would’ve learned something. And so that’s sort of encapsulating in 8,000 words, right? Very short book things that individuals do to strengthen their connections to other people. So about half of our happiness is due to the quality of our social relationships. It’s not quantity, it’s not how many Facebook friends I have, it’s the quality of those relationships. So how do I build that quality?

So the book is basically science-based, not basically it is science-based, and it goes through the 45 cardinal virtues and gives people exercises to connect more effectively to the things around them and goes through the science very briefly. Here’s the definition of this. Virtue gratitude or honesty or being trustworthy says, okay, practice doing these things. They’re a little bit hard. They’re going to be a stretch. But just talking to strangers in elevator that stretch is an important way to really connect to others. And they’re basically these pro-social behaviors. The virtues are pro-social, right? The opposite are like the seven deadly sins. Those are deadly because they’re all selfish. They’re all about me being more important than you. And if I want to strengthen my relationship with others, I’ve got to give to others. And these are just some exercises to do to make that more comfortable to do.

Christin Thieme: Ways to be more intentional. Dr. Zak, this is so fun. Thank you so much for sharing. I like to ask as a last question on our show. What is bringing you joy right now?

Dr. Paul Zak: Such an unfair question, Christin. The easy answer is my children. But I think more fundamentally, I feel like, and this is another part of the happiness equation, I have real purpose in life at this stage in my life. I continue to develop knowledge and technologies and share these with the world. We have a bunch of free technologies we’ve made so that everyone can measure the strength of their social connections, can live happier lives, can really thrive in the broad sense. And a lot of that is by giving. And I think the paradox is that even if you’re the most selfish person ever, and you want to live a longer, healthier life, you have to give to other people because you need to be embedded in community. So for listeners, find those community experiences where you can help out volunteer, be part of a mission to make the world a little better place.

Additional resources:

- Find more from Dr. Paul Zak and how to put this into practice in his latest book, “The Little Book of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Living Better” (Houndstooth Press, 2025).

- What if one small story could spark hope? Join our free 5-day email course, Find Your Story: Share the Joy. Discover how everyday moments from your own life can encourage courage and kindness in others.

- If you are enjoying this show and want to support it, leave a rating and review wherever you listen to help new listeners hit play for the first time with more confidence.

- If you want to help The Salvation Army serve more than 27 million Americans in need each year, give today. Your gift of money, goods or time helps The Salvation Army do good all year in your community.

Listen and subscribe to The Do Gooders Podcast now.