We’re exploring what it means to put Hope in Action. And today, I’m excited to welcome a guest who has dedicated his career to understanding hope not just as a feeling, but as a measurable, teachable strength that transforms lives and communities.

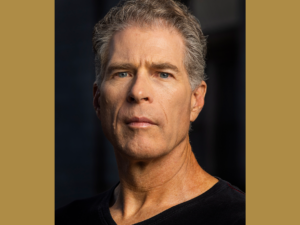

Dr. Chan Hellman is recognized as one of the world’s leading hope scholars, with more than 25 years of research, training and teaching experience. His groundbreaking work has shown that hope isn’t just a nice concept—it’s a powerful predictor of well-being that can be built intentionally.

As the Founding Director of the Hope Research Center at the University of Oklahoma-Tulsa and a professor at the school’s Anne & Henry Zarrow School of Social Work, Dr. Hellman has authored over 150 scientific publications and co-authored the bestselling book “Hope Rising: How The Science of Hope Can Change Your Life.“

His research has been cited in more than 2,700 scholarly publications, and his Hope Centered and Trauma Informed® framework has been implemented across human service organizations, school districts, court systems and communities worldwide.

When Jane Goodall wanted someone to lead a workshop on hope for her global summit with over a million participants, she called Dr. Hellman. When organizations like the Oklahoma Department of Human Services wanted to reduce burnout and turnover while improving client outcomes, they turned to his science of hope.

In today’s conversation, we’ll explore what hope actually is, how it’s different from wishful thinking, and most importantly—how we can build it in ourselves and our communities through intentional action.

Show highlights include:

- What first drew Dr. Chan Hellman to study hope.

- How his definition of hope differs from common misperceptions about it.

- His framework for understanding hope.

- The different ways hope physically affects our brains and our bodies.

- What makes one person more hopeful than another.

- Practical strategies for building hope.

- More on pathways thinking in practice.

- How to strengthen and nurture willpower.

- The difference between individual and collective hope.

- How to recognize a culture of hope.

- What ‘hope in action’ looks like in practice.

- How a group like The Salvation Army can apply a multi-tiered approach to serving both the people we work with, our internal teams and ourselves.

- What surprises Dr. Hellman most about how hope works in people’s lives.

- A concrete action to start building more hope today.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Dr. Chan Hellman: I’m Chan Hellman, and I’m a professor at the University of Oklahoma and I’m the director of the Hope Research Center. We do both research as well as train organizations and communities on the science of hope to promote well-being, especially in the context of trauma and adversity.

Christin Thieme: You’ve really dedicated your career to researching hope. What first drew you to study hope itself?

Dr. Chan Hellman: So when I came to the University of Oklahoma, I was hired to teach statistics and research methods to social work students. And I wanted it to be more than just a course that they took or were required to take. So I started a research center and it is a student-led organization and we partner with community-based organizations to measure outcomes and impacts of program services on children, adults and families. So really have worked in the of domestic violence, child maltreatment and homelessness. And then about 18 years ago stumbled into the concept of hope purely by accident and was really just taken by the definition. And I saw that the definition of hope is actually the single best descriptor of the work that’s taking place in our communities. And so I started researching hope in the context of well-being and consistently find that hope as a psychological strength is one of the strongest predictors of our capacity to thrive.

Christin Thieme: Seeing you define hope as a belief the future can be better than our past, and that we have a role to play in making that future a reality, how does this definition differ from sort of the common misperceptions about hope?

Dr. Chan Hellman: So we typically use the word hope. I hope you have a good day. I hope you’re well. I’m in Oklahoma, so it’s that season where we say, I hope there are no tornadoes today. But as I understand that phrase, I hope you are well, I may have the desire for that, but I have no control, no pathways for it. So we typically use the word hope when what we really mean is a wish. And the definition that you just shared shows that hope is a mindset that is focused on taking action to pursue that future that we desire. So it’s more than wishing and it’s not an emotion.

Christin Thieme: I know you have framed hope around three key elements. Can you help us to better understand this framework and why those various components are essential to understanding hope?

Dr. Chan Hellman: This is actually what I really love about the concept of hope is how simple it really is. It’s based upon, as you said, goals, pathways and willpower where goals are the cornerstone. So from the moment we wake up until the moment we go to bed, we are pursuing goals in our life. As humans, we are goal driven. The question with hope is whether or not we have the ability, capacity, or access to finding the roadmaps or the pathways to pursue those goals. So pathways thinking is the strategizing piece of hope. The final component, willpower, is the ability to focus my mental energy, my attention and intention on those pathway pursuits. You have to have both pathways and willpower in order to be considered hopeful.

Christin Thieme: And you said hope really affects our well-being. What are the different ways that hope actually physically affects our brains and our bodies?

Dr. Chan Hellman: That’s a really good question for both our brains and our bodies. So let me talk a little bit about psychologically this capacity for hope and the way that I study it in the context of trauma and adversity. For me, hope is not light at the end of the tunnel. Hope is light in the tunnel. And so it’s this ability to take one step towards a pathway around a goal that we desire. And so the research shows what we have found is that our capacity to nurture hope helps us cope with daily stress. It is a significant protective factor to depression and anxiety, for instance. We also become much better at self-regulating our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors when we nurture hope.

The brain piece is actually really interesting and fairly new. I’m partnering with Dr. Daniel Amen of the Amen Clinics, and we have over 10,000 brain scans looking at where hope is located in the brain and demonstrating that when hope is nurtured, the areas of our brain that protect us from anxiety are strengthened. And so not only is it a psychological strength, but there are also biological markers of its importance.

Christin Thieme: So based on all your research, what is it that makes one person more hopeful than another?

Dr. Chan Hellman: One of my guiding principles that I use when I teach people about hope is that hope is a social gift. Hope is not something that happens in isolation with us. It happens in relationships. And so we know that connectedness to others, connectedness to something greater than ourselves is really that catalyst that begins to nurture hope.

Christin Thieme: A lot of your work has pointed toward the fact that hope can be taught and strengthened over time. So what practical strategies have you seen that are effective in actually building hope in someone who needs it?

Dr. Chan Hellman: So a couple of things really. One of the things that I think is really important is one of our students finished her dissertation focused on looking at three and four-year-olds and how they not only learn what hope is but their ability to teach it to their parents. So we know that hope is something that can be taught and nurtured across the lifespan.

When you and I are experiencing adversity, not just trauma, but high stress, we’re much more likely to set goals that are avoided in nature, meaning we’re much more likely to set goals around outcomes that we do not want to occur. And so some of the strategies we’re developing is really looking at short-term specific goals. So when people learn that hope is this belief that the future can be better, it’s made up of those three components, it’s different from wishing, but then we have to really lean into hope for what. So we start to really focus in on what are your goals in the very specific domains of your life, housing, relationships, your health, education, employment, and then begin identifying viable strategies to pursue those. So short-term specific may mean what do we want to achieve or work towards this week? In a study we published among those who are experiencing homelessness, what we found is that we have to focus on today. What are the goals we have today and what are the strategies in the steps necessary to get there today?

Christin Thieme: So that first piece, those hope-building goals, one of the strategies is short-term thinking. How does pathways thinking work in practice? And can you share an example of how helping someone identify those routes to their goals?

Dr. Chan Hellman: So pathways thinking is really a skill and it is a skill that can be strengthened. And we learn these strategies to achieve our goals across experiences. So it’s constantly evolving within us. And so one visual representation that might be helpful is if you or I or your audience types in an address in their smartphone, the map app is going to give them three different routes. Those are pathways. Each of those pathways have barriers. So we can look at each of those and say, which one is the most viable for us? And that’s really what pathways thinking is.

Now, pathways thinking is not very strong for children because they just haven’t had that experience. And then individuals who’ve experienced trauma and adversity really struggle with how to get there from here. And so when I go back to this idea of hope as a social gift, what we want to do is start to identify who are the potential hope models that we can look to on how did they get there from here? So many different strategies, but those come to mind pretty quickly.

Christin Thieme: Then that third piece of willpower, just the idea of willpower takes this idea of mental energy, having the agency to decide you’re going to do something. How do you go toward that when you’re already in a moment of stress?

Dr. Chan Hellman: So it’s really important to recognize that willpower is a limited resource, and throughout the day, you and I are depleting that resource. So we go home at the end of the day, mentally exhausted or emotionally exhausted. That’s the depletion of that willpower. So it’s really important for people to understand that willpower is not something you either have or don’t have. It’s a limited resource. When we’re in a very high stress environment, we can get into a sense of urgency. And so strategies like mindfulness practice, breathing, contemplative prayer, yoga, these are all strategies to help settle that willpower and it can be done in a very, very short amount of time.

Absent of that, one of the things that we can do to strengthen and nurture our willpower is to think about a time when you’ve achieved something really difficult in your life and how did you get there from here? How did you overcome those barriers? And reflecting on those past successes tends to give us a boost of that energy, and it also reminds us that we’ve done hard things before.

Christin Thieme: So we’ve been talking a lot about hope on an individual level. Does hope for individuals differ from sort of a collective hope maybe in a community or in an organization like The Salvation Army? Is there a difference?

Dr. Chan Hellman: Yes. I’m so glad that you asked that. We actually have a new publication that is going to come out in the next couple of months where we created a new conceptual model around the idea of collective hope. And collective hope in an organization or a community is not the average of everybody’s individual hope. Collective hope is when I believe that the leaders of my group or organization can cast a clear vision of where we’re going and that our team has the capacity to get there from here, and that there is a shared energy around that common goal. We were actually finding that within organizations, collective hope is a significant protective factor to burnout, secondary traumatic stress, improved engagement, improved goal attainment of teams. It’s a really exciting new area of research.

Christin Thieme: When you talked about the leaders specifically, are indicators that a group has successfully built a culture of hope? Can you recognize it?

Dr. Chan Hellman: Yeah, you can. When we do trainings in organizations, it’s very clear that people can see hope. So for instance, I believe it was Gallup who actually looked at the hope levels of leaders and then independently had employees rate the characteristics of those leaders. And what they found is that when leaders score higher in hope, employees tend to see them as more transformational. But when leaders score lower, employees tend to see them as more transactional in their relationship. So it certainly influences our behavior.

Christin Thieme: We’re talking a lot in our coming episodes about this idea of hope in action. Based on all of your research and the work that you do, what do you think hope in action looks like in practice?

Dr. Chan Hellman: So for me, it’s when we have a unifying language across different organizations or different systems. Now I work in the space of high trauma, and so when I see state agencies, community partners, the courts, public safety all using the same language, where well-being is the collective outcome shared by those groups, that’s when I see hope in action.

Christin Thieme: How can a group like The Salvation Army apply these really multi-tiered approach to serving both the people we work with and our own internal teams and to our own selves as individuals? What’s sort of your starting point here for people?

Dr. Chan Hellman: First of all, I love the way you frame that because it’s exactly how we focus our training. It’s a multi-tiered, multi-level approach and where leaders begin to understand not only what hope is, but how important it is to create a culture, a workplace culture that nurtures hope. I’m a big fan of Brene Brown, and so when I think about the idea that we can’t give what we don’t have, the idea of creating a culture where the workforce is well so that they can do well. And then when programs services begin to really focus on recognizing that their programs are actually pathways of hope and that the individuals or the communities that they’re working with can set goals and recognize again that The Salvation Army is in fact a pathway for families.

Christin Thieme: What has surprised you most about how hope works in people’s lives?

Dr. Chan Hellman: I have to tell you that where I’m at right now is, and I work with so many different schools, school districts, state agencies, law enforcement community, nonprofit organizations, I’m in this space where I believe that most people who are doing this hard work in our communities, that it’s a calling that they’re being called to do that service. And I really think that we have a system where wellbeing is the reduction of what’s wrong. And I think this language of hope reignites that calling that people have, it’s a core value of who they are. And so it’s just really exciting to watch people really start to consider and lean into hope as a science, but also hope as a fundamental framework that leads to wellbeing.

Christin Thieme: For someone listening who wants to build more hope right where they are right now, what’s a concrete action that you would recommend they start with?

Dr. Chan Hellman: The first thing is identify what you want to achieve. And I would say practice what do you want to achieve today? If you want to sit down and have a meal as a family, set that as the goal and then figure out how do you get there from here? What’s the first thing that you can do right now? One of our guiding principles in the science of hope is very clear that hope begets hope. And just taking that first successful step shows you that that goal is possible, and that’s the essence of hope.

Christin Thieme: Finally, Dr. Hellman, what is giving you hope right now?

Dr. Chan Hellman: Honestly, for me, I think it’s seeing this connection in teachers and case managers. It just fills me with so much joy to see people go from this emotional exhaustion space back to this energy and commitment that there’s just something about watching. It’s something I fell in love with 20 plus years ago in working with nonprofits, that passion, it’s pretty easy for me to get caught up in that.

Additional resources:

- If you are one of the hopefuls, get on the list for the Do Good Digest, our free 3-minute weekly email newsletter used by more than 20,000 hopefuls like you for a quick pick-me-up in a busy day.

- If you are enjoying this show and want to support it, leave a rating and review wherever you listen to help new listeners hit play for the first time with more confidence.

- If you want to help The Salvation Army serve more than 27 million Americans in need each year, give today. Your gift of money, goods or time helps The Salvation Army do good all year in your community.

Listen and subscribe to the Do Gooders Podcast now.