Dr. Stuart Brown invites each of us to rediscover our unique “play personalities.”

His directions were precise, though unusual for a meeting: “follow the big Eucalyptus trees along the right side of the road; cross the first of two one-lane bridges, go right and then cross the next bridge; go past one house and turn left; proceed ahead until you see the treehouse.”

And there it was—a one-room treehouse accessible by steps, ladder or rope swing, with wild turkeys roaming below. I’d arrived at the office of The National Institute for Play in Carmel Valley, Calif., to meet Dr. Stuart Brown, its founder, who had just returned from a game of tennis.

“It’s a very different game in my eighties than it was at 35,” he said “It’s more jocularity across the net than being about who hit the best ball; it’s more social, but it’s still play.”

And he would know. He’s the expert—a medical doctor, psychiatrist, clinical researcher, and for the past few decades, a student of play, which he says is a public health issue.

“It’s all around us, yet goes mostly unnoticed or unappreciated until it is missing,” Brown said. In his book, “Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination and Invigorates the Soul,” he defines play as “a state of mind, rather than an activity…an absorbing, apparently purposeless activity that provides enjoyment and a suspension of self-consciousness and sense of time.”

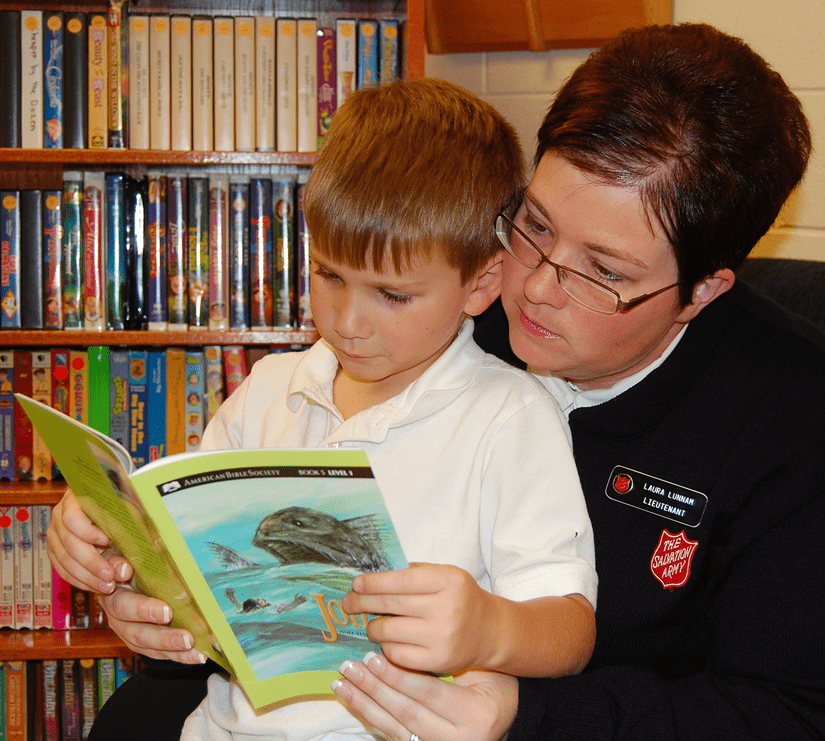

He has studied animals, watching rats laugh or a polar bear and husky “rough-and-tumble,” as well as people—from the “anarchy” of a preschool playground to conducting “play profiles” of over 8,000 people in an effort to link their play history with current opportunities. As a result, The National Institute for Play defined seven types of play, from attunement, such as an infant making contact with her mother and responding with a smile, to movement play, such as tennis.

Brown teaches a course at Stanford University called “From Play to Innovation” that investigates the human state of play and its development to promote innovation in the corporate world. With the institute, he is committed to “bringing the unrealized knowledge, practices and benefits of play into public life” and so he shared more:

– Body play and movement

– Object play

– Social play

– Imaginative and Pretend play:

– Storytelling/Narrative play

– Creative play

See more at nifplay.org

What is play?

Play is a real fundamental aspect of complex, social mammal life, and has a place in the life of many species. In terms of humans, it is something that is done for its own sake, it’s pleasurable, it allows you to become in a different sort of state of being. You are freed from the constraints of time, and the outcome of what you’re doing or even thinking or imagining is less important than the experience itself. It is the basis of all art, games, books, sports, movies, fashion, fun, and wonder—in short, the basis of what we think of as civilization. Play is the vital essence of life. It is what makes life lively.

Where does play originate?

Play, from an evolutionary point of view, emerged as an organizing way to explore your environment and get along with your species. Nothing lights up the brain like play. Three-dimensional play fires up the cerebellum, puts a lot of impulses into the frontal lobe—the executive portion—helps contextual memory be developed, and so much more. We are empowered and engaged by things in our play nature, and we are pre-programmed to play throughout our lives. We know that when one is play deprived, the brain doesn’t develop normally. The opposite of play is not work; it’s depression.

How did depression and aggression lead you to study play?

We extensively studied Charles Whitman after the Texas Towers shooting in 1996 that left 17 people dead, looking for causes in his life. We discovered that he was raised in a tyrannical, abusive household. His playfulness was suppressed by his father, and the committee ruled that a lifelong lack of play deprived him of opportunities to view life with optimism and that was a key factor in his homicidal actions.

More recently, if you look at mass shootings from Newtown, to Aurora and Virginia Tech, there’s no single linkage that connects all of the shootings, but if you look closely at the life histories, all of them had play deprivation. That is a common theme, though it may be correlational rather than causative.

There is a cultural shift away from free play, and those shifts are associated with increased obesity, childhood depression, fostering ADHD statistics, and one’s ability to handle aggression and deal with delay of gratification and establishment of social empathy, which is learned in the hallways of childhood play.

How does play develop social empathy?

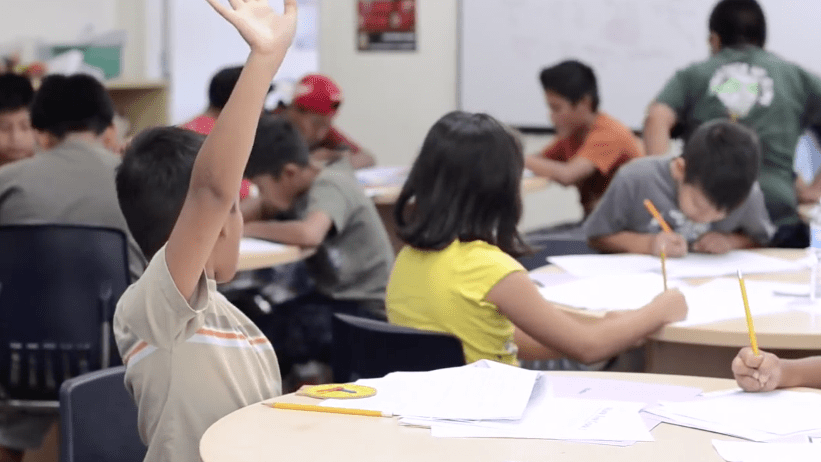

If you were to watch preschool kids, ages 2 to 4, on a playground of a school that understands the dynamics of healthy play, you’ll see squealing, chasing, screaming, and punching anarchy. It’s noisy. In that rough-and-tumble play, kids are self-regulating—they learn to share, that if they’ve been punched hard it hurts and so they won’t punch someone else, about exclusion and inclusion and social nuances. Socialization requires the ability to share and the capacity to feel for others, and that’s learned primarily in open play settings.

If an adult doesn’t understand that and wants orderliness and quiet and suppression of the anarchy, then chances are the social learning of those kids is going to be stunted and they’ll have a lesser capacity for social empathy. It’s learned just as you learn a language.

What is in your own play history?

I grew up on the southwest side of Chicago and even in the winter, my family had a picnic every weekend in the forest preserves. We were a very playful, loving family. My parents were Presbyterian; my mother was a trustee in the Moody Bible Institute and my father was an organic chemist. I loved to be outside and roamed everywhere until all hours. Then I went to medical school, which was rigorous, and had two residencies in highly academic, competitive environments. I became assistant dean of a medical school very young; I was ambitious and play deprived. Whitman opened my eyes to the significance of play for me and for my family.

Is play at odds with productivity?

It’s innate to keep playing.

The cultural historic trends through the Industrial Revolution were that productivity is the hallmark of personal health, and that if you’re not being productive, if you’re not getting As in school, if there isn’t a discernable goal or outcome of what you’re doing that you’re being trivial or superficial. That cultural norm, I think, goes against who we really are biologically and as a species. When you analyze the play histories of people and see contributions of adequate play toward empowerment and competency, and on the other hand you see the consequences of serious play deprivation, you begin to sense that it has its place in every life throughout the world. Play’s contribution to flexibility and adaptation, and I would say spiritual health, are very significant.

How can someone recapture his or her play personality?

If you have enough freedom of choice in your life and you recognize that this is an important element in becoming productive and fulfilled, chances are you can rediscover and enjoy your play nature—music, movement, socialization—there are a lot of avenues into gaining one’s play nature back. Everybody’s got it, it’s just a matter of honoring it and finding how to best implement it.

I would encourage you to explore backwards as far as you can go to the most clear, joyful, playful image that you have—a toy, a birthday or a vacation. Begin to build from the emotion of that into how it connects with your life now. You can enrich your life by prioritizing it and paying attention to it.

What is your play personality?

Dr. Stuart Brown says most people recognize themselves in these archetypes and find them useful for discovering their own play personality. Identify your play personality to achieve greater self-awareness and greater play in your life.

The Joker

A joker’s play always revolves around some kind of nonsense. The class clown finds social acceptance by making other people laugh. Adult jokers carry on that social strategy.

The Kinesthete

Kinesthetes are people who like to move, who—in the words of Sir Ken Robinson—“need to move in order to think.” Kinesthetes naturally want to push their bodies and feel the result.

The Explorer

Each of us started our lives by exploring the world around us. Some people never lose their enthusiasm for it. Exploration becomes their way of remaining creative and provoking the imagination. It can be physical, emotional or mental.

The Competitor

The competitor enjoys a competitive game with specific rules, and plays to win. The competitor loves fighting to be number 1. It can be solitary or social, be actively participated in or observed as a fan, and translates into the business world, where money or perks serve to keep score.

The Director

Directors enjoy planning and executing scenes and events. They are born organizers. At their best, they are party givers. At worst, they are manipulators.

The Collector

The thrill of play for the collector is to have and to hold the most, the best, the most interesting collection of objects or experiences—anything and everything is fair game for the collector.

The Artist/Creator

For the artist/creator, joy is found in making things. They may end up showing their creations to the world, or may never show anyone what they make. The point is to make something—to make something beautiful, functional, goofy, or just to make something work, taking something apart, cleaning it and putting it back together.

The Storyteller

For the storyteller, the imagination is the key to the kingdom of play. Because the realm of the storyteller is in the imagination, they can bring play to almost any activity.

For more, read “Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul” (Avery, 2009) by Dr. Stuart Brown with Christopher Vaughan.